| Mo Stokes:

The Greatest Basketball Player You've Never Heard of... |

“Maurice Stokes was Magic Johnson before there was a Magic Johnson.”

--Boston Celtics Coach Red Auerbach |

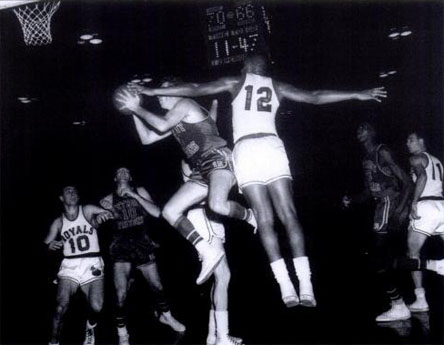

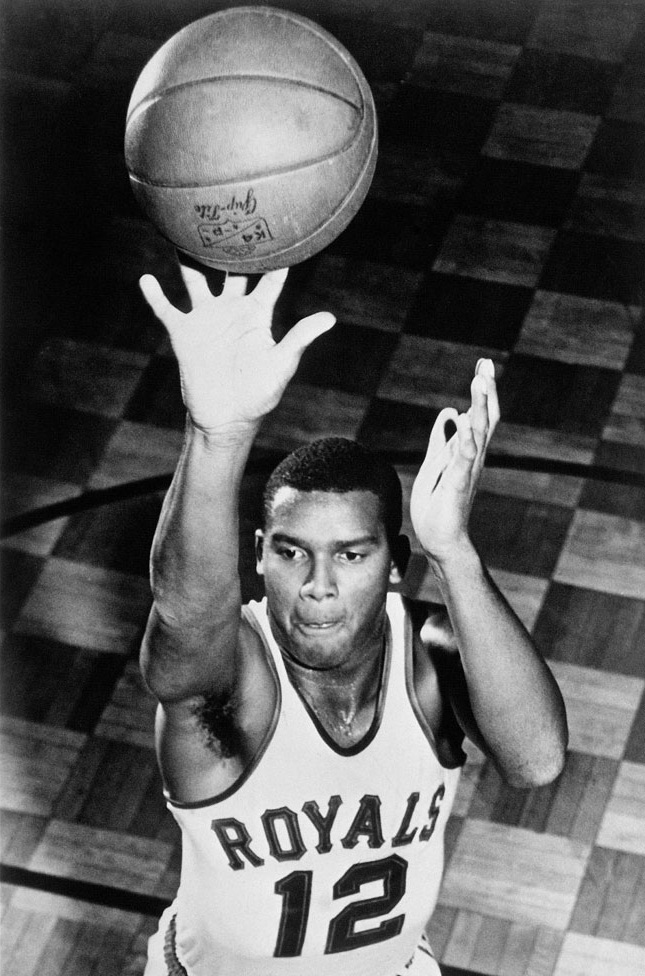

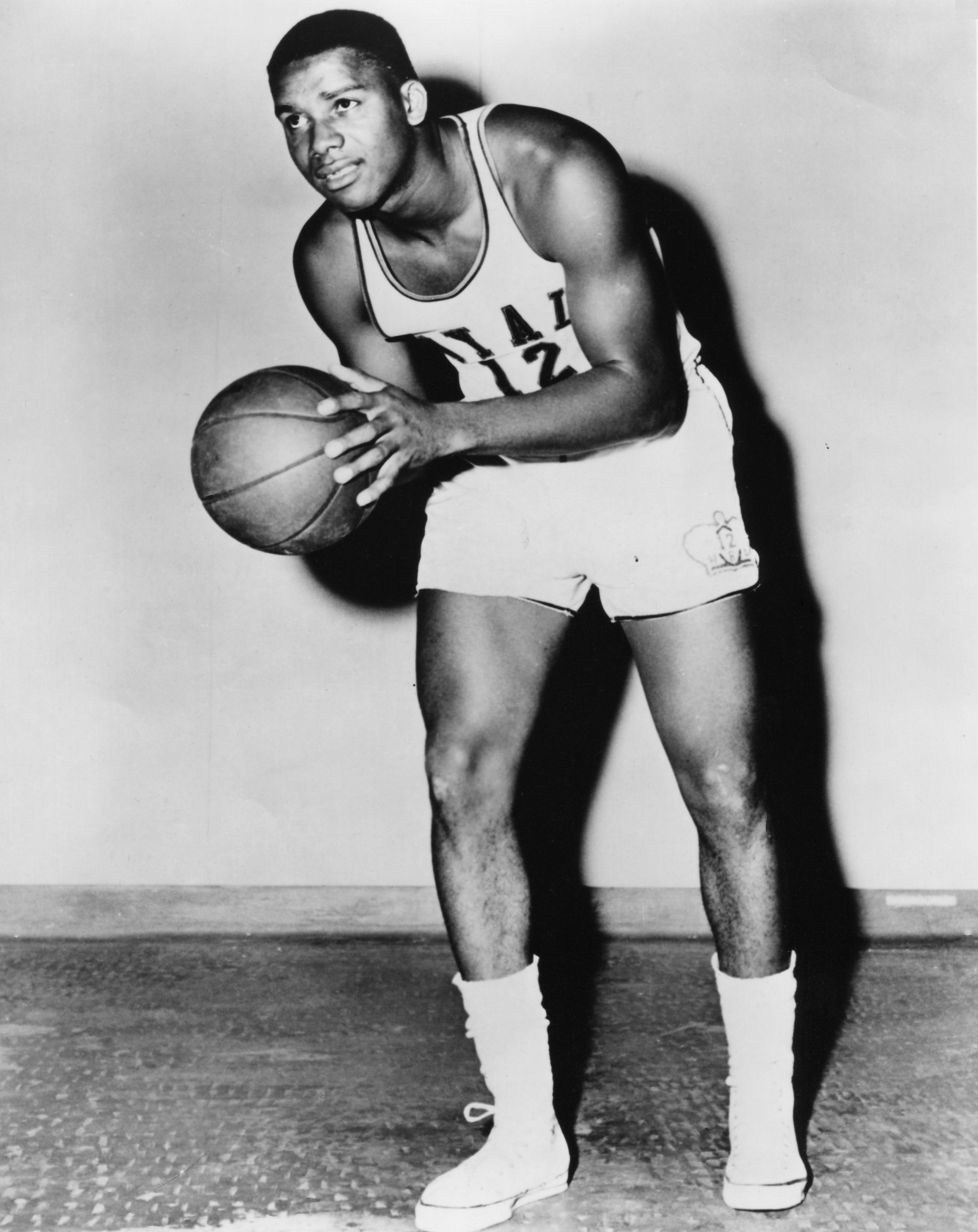

He was one of the greatest basketball players of all time. In private life he was a soft-spoken guy wearing horn-rimmed glasses, but on the basketball court he was one of the most feared competitors of his day. During his NBA career, he averaged 16.4 points, 17.3 rebounds, and 5.3 assists per game. He played in the All-Star Game every season as a pro. By his third season, he was second only to Bill Russell in rebounds, and Bob Cousy and Dick McGuire in assists. He was the first three-way threat (points, rebounds, assists) in professional basketball, and perhaps the most talented all-around player to ever appear in the NBA, but the odds are you've never heard of him.

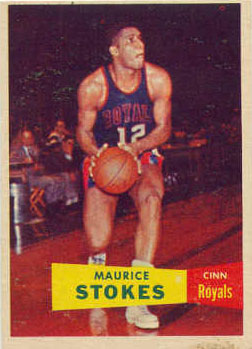

Maurice Stokes was born on June 17, 1933, to a poor family in Rankin, Pennsylvania. His father worked in the steel mills, and his mother was a domestic. From these humble origins, Stokes grew up to play for the NBA's Royals (now the Sacramento Kings) from 1955 to 1958.

"He was a coach's dream," said Hall of Famer Bobby Wanzer, who coached and played with him. "If things had worked out differently, Maurice would have become one of the top 10 players of all time." In 1992, former NBA player and coach Gene Shue described him as "competitive, hard-nosed, tough." In fact, Stokes turned out to be a lot tougher than anything the NBA, or even life could throw at him.

The Stokes family -- Maurice, his parents, two brothers and twin sister -- moved to the Homewood section of Pittsburgh when he was eight. At George Westinghouse High School on North Murtland Avenue, Stokes was a two-year starter on the basketball team, and they won back-to-back city championships in 1950 and 1951.

Stokes and his best friend Ed Fleming were the co-captains of Westinghouse's 1951 city championship team -- the only two black starters. They also played sandlot basketball pickup games at Homewood Park, in a never-ending contest in which the winners kept the court and were challenged by the next five players. Despite the sewer gratings and obstructing poles, "it was the best there was at the time," recalled Fleming.

"Chuck would be arguing with them about how good (black players) were," Brown said. "When Mo came out of college, Chuck told them ahead of time 'this is a man who's going to show you how it's done.'"

--Harold Brown, friend of Chuck "Tarzan" Cooper, from the book 'They Cleared the Lanes: The NBA's Black Pioneers', by Ron Thomas.

|

Celtic Chuck Cooper (NBA photos) |

At this time, Stokes was befriended and mentored by a famous Westinghouse graduate named Chuck "Tarzan" Cooper, seven years his senior. Cooper had just become the first black player drafted into the NBA, selected by the Boston Celtics in the league's 1950 draft. (The New York Times reported that one dismayed team owner complained to Celtic head Walter Brown, “Walter, don’t you know he’s a colored boy?” To which Brown responded, “I don’t give a damn if he’s striped, plaid, or polka dot! Boston takes Chuck Cooper of Dusquene!")

Maurice and Fleming began playing ball with Cooper during the summer at Mellon Park, on the corner of Fifth and Penn. The public courts there drew the city's best high school, college, and pro players in the 1950s. "The chance to play with guys who had made it in the pros during the summers at Mellon Park -- to sit and talk with them -- was important," Fleming said.

The action at Mellon Park was non-stop, from morning to night, as teams competed in games of ten buckets. "The asphalt got so hot you had to take your shoes off," Fleming remembered. Stokes and Fleming began making the trek from Homewood each day: "It was a long walk for us to get there, but when we did it was pure basketball against the best the city could offer." The ratio of black to white players was about two to one, and the games were rarely marred by racial tension. One sweet-shooting, skinny white kid they played there, named Jack Twyman, would not only go on to become an NBA All-Star and a Hall of Famer, he would one day become Maurice's greatest friend.

After beating the local teams, Maurice and Ed would hang out at Cooper's home, eat rich meals prepared by Cooper's wife, listen to his jazz and R&B records, and -- if they asked really nice -- borrow his top-of-the-line Olds 98 convertible, to drive to Mellon Park for more basketball, or around town to impress the girls.

It was obvious from Cooper's lifestyle that you could make good money in the NBA, but he also told them stories of the racial prejudices in the league that he was constantly struggling to overcome. On barnstorming exhibitions in the South, the Celtics had to leave Cooper behind, because of the angry crowds and the difficulties in even finding him hotel rooms. But unlike Jackie Robinson in baseball, Cooper was not stoically silent in his battle to overcome racism: Once when an an opposing player shouted "I got the nigger," and Cooper shot back "And I got your mother in my jockstrap." In 1952, the taunts finally escalated into a fistfight during a game against the Milwaukee Hawks.

But Maurice didn't need Cooper to prepare him for the prejudices he would face as a black athlete: In Maurice's poverty-stricken area of Pittsburgh, neighborhoods, restaurants, and even swimming pools were racially segregated. In 1947, after picketing led by Urban League staffer K. Leroy Irvis, downtown department stores were forced to hire black clerks -- but many stores still wouldn't let black customers try on clothing.

Basketball would be Mo's means of escape from the poverty and degradation. He was determined to live where and how he wanted. Stokes received ten basketball scholarship offers from various schools, and looked for a calmer, more tolerant place to live than Pittsburgh.

"Maurice Stokes was a moose of a man, the first star the franchise had. At six feet seven and 250 pounds, he was stronger and a better shooter than Elgin Baylor."

--Oscar Robertson

|

|

Maurice finally chose to attend St. Francis College, a tiny division one Catholic liberal arts university in Loretto, Pennsylvania, with under 700 students. It was founded in 1847 and conducted under the tradition of the Franciscan Friars of the Third Order Regular. It was one of the first Catholic Universities in the United States and the first Franciscan college in the nation. The university is situated on 600 acres in the forests and farmland of Loretto, Pennsylvania. Obviously, this was a big change from the segregated streets of Pittsburgh.

Maurice turned them into a college basketball power. He averaged 23.3 points and 22.2 rebounds per game in his junior year as his team went 22-9 and played in the National Invitation Tournament (much bigger then than the NCAA is today). As a senior All-American, he led the "Frankies" to a fourth place finish at the NIT, where he scored 43 points in a 79-73 overtime loss to Dayton, and was named the tournament's MVP in what The New York Times called "one of the most dazzling individual exhibitions ever seen here."

"The first great, athletic power forward. He was Karl Malone with more finesse."

--Bob Cousy

|

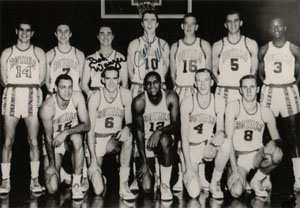

The 1956-57 Rochester Royals: Back Row -- Richie Regan, John McCarthy, Bob Wanzer, Jack Twyman, Tom Marshall, Dave Piontek, Ed Fleming. Front Row -- Dick Ricketts, Art Spoelstra, Maurice Stokes, Lew Hitch and Bob Burrow. |

Following a brilliant college career in which he averaged 22 points and 24 rebounds per game, the Harlem Globetrotters and various industrial teams pursued Stokes after his senior season. But then the NBA's Rochester Royals chose Stokes number 2 overall in the 1955 NBA draft -- after Milwaukee picked Maurice's boyhood rival from the playgrounds of Pittsburgh, Dick Ricketts of Duquesne. They also chose Ed Fleming, and in the second round, none other than Jack Twyman, from the Mellon Park days, who had become a star as well, at Cincinnati. The three youths even drove to training camp together. Although Stokes was drafted first, Twyman was sure to remind him that he outscored Maurice by one point in their final NIT matchup.

In Stokes' NBA debut he had an amazing stat line of 32 points, 20 rebounds, and 8 assists, in the days when any one of those stats would seem impossible. By the end of the season he held averages of 17 points and a league best 16 rebounds per game. He even grabbed 38 rebounds in a single game, and was named 1955-56 NBA Rookie of the Year. He was so dominant that Ricketts, drafted #1 before Stokes, was traded the Royals to play in support of him.

"If you were playing with Maurice and he got the rebound, your best move would be to take off and go because he didn't need you to help him bring the ball down," said Ed Fleming.

"I can remember a reporter asking me on a plane, since I had played with Baylor and Stokes, which was better. My response was that I thought Maurice could stop Elgin but Elgin couldn't stop Maurice."

--Ed Fleming

|

|

The next season, Maurice set a league record for most rebounds in a single season with 1,256 (17.4 per game). He finished with averages of 17 points, 17 rebounds, and 6 assists per game, improving in practically every category. Stokes and other black athletes were revolutionizing the NBA (mainly by playing something previously unseen in the league, called "defense").

In Stokes' third season in the NBA, his team moved to Cincinnati, and the bigger crowds brought bigger numbers from Maurice. He averaged 18.1 rebounds per game (second to only Bill Russell), was ranked third again in assists (6.4, behind only guards Bob Cousy and Dick McGuire), and scored 16.9 points a game, putting him in the top-15 scorers in the league. The best passer on his team, he may have been the only center in NBA history to routinely lead his team's fast break. There wasn't a player on the planet who could compete with his all-around game.

"Had Maurice lived and stayed healthy, people wouldn't be talking about the Celtics dynasty as they do now. With Oscar Robertson, Jerry Lucas, Wayne Embry and myself -- with Maurice -- the Cincinnati Royals would have been much more of a factor.”

--Jack Twyman |

|

But on March 12, while playing against the Minneapolis Lakers in the last game of the 1957-58 NBA regular season, Stokes battled under the basket with Vern Mikkelsen for a rebound and crashed to the floor. He was knocked unconscious as his head hit the hardwood. Stokes was revived with smelling salts, and eventually returned to the game, seemingly uninjured by the fall, and was the game's high scorer, with 24 points.

After the game, the team went straight from the arena to the train station, and traveled all night to Detroit, where they were favored to win a best-of-three game series against the Pistons, in Stokes' first playoff appearance.

But about a half hour before tip-off, Maurice and teammate Jim Paxson became nauseated and vomited. Everyone figured it was a virus, and were only concerned as to whether or not Stokes would feel strong enough to play that night.

Maurice was lethargic in warmups, but he played the game, in a weak (for Stokes, anyway) 12-point, 15-rebound performance in his first NBA playoff game, a loss.

"When we got back to the hotel, we went across the street to have some beer before we went to the airport. Although I had not played well, I never had any idea that there was something wrong. But when we arrived at the airport, I began to feel sick and weak. I remember some of the ballplayers saying, 'Try and make it back to Cincinnati.'"

--Maurice Stokes, from his unpublished autobiography. |

The team took a bus to the Willow Run Airport at Ypsilanti, to catch a flight back home. Then about ten minutes into the flight, Stokes became ill again. "I feel like I'm going to die," he told Dick Ricketts.

About 45 minutes outside of Detroit, Stokes began to shake and writhe in what teammate Jack Twyman described as "a violently ill" seizure. "He was sweating, soaking wet all over, as if someone had dipped his head in a swimming pool," Twyman said. Stokes collapsed, his breathing erratic and shallow. An airline stewardess fed him oxygen as Maurice requested to be baptized -- apparently he had gone to St. Francis more for the un-Pittsburgh-like atmosphere than for religious reasons. But now Maurice wanted to become a Catholic before he died. Teammate Richie Regan, a Catholic, informally baptized him.

At this crucial moment, the plane was still an hour and a half from Cincinnati. After some very animated discussion, despite the worries of some of the terrified players, it was decided by the team owners and NBA President Maurice Podoloff, who were also on the plane, that the plane wouldn't turn around, but would take the extra half hour to fly ahead to Ohio.

"While we were in the air, they called ahead for an ambulance to be at the airport. I don't remember getting into the ambulance. At that time I would regain consciousness for a while and then I would black out."

--Maurice Stokes, from his unpublished autobiography. |

|

When the plane finally landed, Maurice was rushed to the hospital. Doctors would later say that only the efforts of the Trans World Airlines stewardess, Jeanne Phillips, had kept Maurice alive. Stokes' brain had swelled after the collision with the floor, and the change in cabin pressure on the flight had worsened it to the point of death. When the swelling did not go down, his motor system -- his ability to walk, talk, control any movement whatsoever -- shut off. Lee Fleming, who had been traded the Lakers a year before, rushed to St. Elizabeth's to see his old friend. "When I got there, Maurice was packed in ice, in and out of consciousness... I just couldn't stay in the room. He started to cry, and I had to go into the hall."

Stokes was packed in ice to battle a 106-degree temperature, paralyzed, in and out of consciousness and near-death. Every moment before passing out yet again must have been terrifying for Maurice, wondering if he would wake again. He had once hoped basketball would take him out of segregated Pittsburgh and allow him to live the way he wanted. Now because of basketball he couldn't even leave his bed, couldn't stand, couldn't eat on his own. His chance at fame, money and glory -- his chance at even walking again -- was seemingly gone. He was twenty-four years old.

"He was a guy lying there without a team. There was no insurance. No compensation."

--Jack Twyman |

| MAURICE STOKES |

| COLLEGE STATISTICS |

| YEAR |

GAMES

|

PPG

|

RPG

|

APG

|

|

1951-52

|

30

|

16.8

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|

1952-53

|

18

|

23.2

|

22.1

|

N/A

|

|

1953-54

|

26

|

23.1

|

26.5

|

N/A

|

|

1954-55

|

28

|

27.1

|

26.2

|

N/A

|

| NBA REGULAR SEASON STATISTICS |

| YEAR |

GAMES

|

PPG

|

RPG

|

APG

|

|

1955-56

|

67

|

16.8

|

16.3

|

4.9

|

|

1956-57

|

72

|

15.6

|

17.4

|

4.6

|

|

1957-58

|

63

|

16.9

|

18.1

|

6.4

|

| ALL-STAR STATISTICS |

| YEAR |

MIN. |

PPG

|

RPG

|

APG

|

|

1956

|

20

|

10

|

16

|

2

|

|

1957

|

31

|

19

|

12

|

7

|

|

1958

|

36

|

10

|

14

|

3

|

|

Meanwhile the Royals played game two without Stokes and lost, ending their season. After the 1957-58 season, they changed ownership groups. The previous owners, the Harrison brothers, threw in the towel and sold the team to a group of local investors headed by Tom Wood and a Cincinnati attorney. A rider in the contract stipulated that the price, $200,000, would rise to $225,000 if Stokes ever played again.

But when it became clear that Stokes' injury was serious, the new owners declined to renew his contract. The small amount of insurance he had was rescinded as well.

The team had scattered back to their hometowns; everyone except for Stokes and Jack Twyman, who lived in Cincinnati. Jack went to work at his other job, for Aetna Life Insurance, and occassionally checked in on his friend, who remained on the critical list for two and a half months. One day Twyman visited the hospital to find Maurice's mother crying outside his room. She hadn't eaten in two days. The hospital had not been paid for services, and the nurses were about to walk out. The family was out of money.

Stokes had about eight thousand dollars in the bank, but they couldn't access it. Meanwhile, Maurice needed a hospital room at $20 per day, three nurses attending him for $36 a day, and an enormous amount of life-preserving drugs. It would cost $100,000 or so a year to keep Maurice alive. He could not live more than a week without round-the-clock care.

These were the days before players were protected by unions, and Maurice had no medical insurance and no pension to fall back on.

Twyman talked to his friend, Judge Chase Davies of the Probate Court, who suggested that as a non-relative and resident of the state, Jack qualified under Ohio law to become Maurice's legal guardian. Twyman helped with medical bills that Stokes’ family could not pay while he and industrial-compensation attorney Walter Beall, came up with a plan: Twyman legally adopted Stokes in order to become his conservator and handle the medical bills and other financial matters. "The club was sold and all the people left town and one thing led to another," Twyman said. "I was in town and I was the logical choice to do it. The other reason we did this was because Maurice was injured on the job and we had to file a claim with the state for him to receive workers' compensation to help defray medical cost.

They had bonded as competitors on the Mellon Park basketball courts, despite being from different races, from different parts of that segregated city. But now that bond became even stronger as Twyman became Stokes' only hope for survival.

"Maurice... was Elgin Baylor and Michael Jordan, before those guys came along, only Maurice was three inches taller and 50 pounds heavier. He was the first player to combine strength and quickness those guys had. ... He would have been one of the five best."

--Jack Twyman

|

|

When Stokes finally came out of his coma, his sense of humor was what actually tipped doctor's off to his true diagnosis. As they were taking tests, one of the technicians made a joke, and amazingly, Maurice laughed -- a "sucking, soundless" laugh, but definitely a laugh. The technicians realized that laughter was a reflexive action, like breathing, blinking or coughing. The doctors then began sticking pins in Stokes' body, and sure enough, he would wince in pain. But other than actions like those, it was impossible for Maurice to do anything. He was fully alert, but his body couldn't respond to the commands his brain was sending. Maurice was diagnosed with post traumatic encephalitis: A brain injury that damages motor skills -- and was 95% fatal at the time.

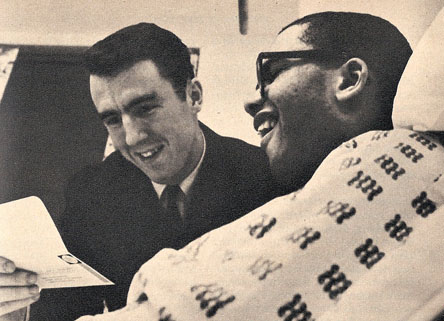

Twyman or his wife, Carole, would come to see him almost every day. Whenever Maurice opened his eyes to see them at his bedside, he was as relieved as they were. Stokes had regained full-consciousness, but still couldn't speak. So he and Twyman communicated by blinking: One for 'yes.' Two for 'no.' Eventually, Twyman would recite each letter until Stokes blinked affirmatively, to spell out words.

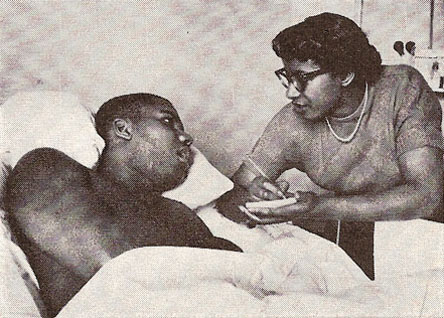

Maurice's sister transcribes his message. (Photo: Saturday Evening Post -- read the article here.)

Maurice's sister transcribes his message. (Photo: Saturday Evening Post -- read the article here.) |

|

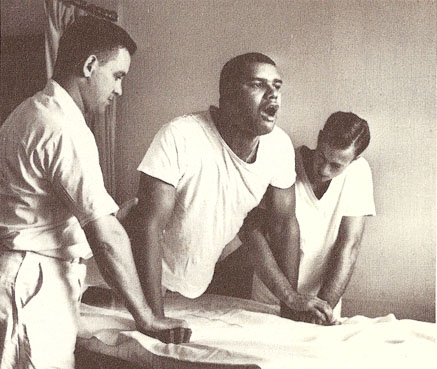

Despite a gloomy prognosis from doctors, Stokes was determined to regain his motor skills, and walk again. He began a steady training regimen, where moving his legs was more gruelling than any basketball practice had been a year before. The doctors had determined that the only way to jolt Maurice's brain into relearning how to control his body was through pain: If joints were bent back far enough, limbs twisted, bones flexed in unnatural directions, Maurice's reflexes would take over to stop the excruciating pain, and re-teach his brain. After years of agonizing therapy, many hours per day, he was able to take small steps down the hospital hallway -- more of a triumph than any slam dunk or block could ever be.

Though his body suffered spasms and his fingers didn't always go where he wanted, Stokes eventually re-learned how to move, to eat, to paint, to mold pottery, to type (over the course of three years he arduously typed out his autobiography, which is still unpublished), and eventually even to speak. "He was a very vital person all the years he was sick," Twyman said. "For 12 years, he never forgot to cast a vote in a local election."

Nor did Maurice forget his sense of humor. Once, Jack playfully commented on Stokes' speaking difficulties, saying "I'm glad the sonofagun can't talk -- you couldn't shut him up, otherwise." Maurice tapped out a comeback on the electric typewriter: "It's better to be quiet and let people think you are a fool than to open the mouth and remove all doubt."

“To see the way he conducted himself, I just stood in awe of him. It got so bad, when I would be having a bad day myself, I would go to see Maurice, selfishly, to say, I want to get pumped up. And he never failed to pump me up.”

“To see the way he conducted himself, I just stood in awe of him. It got so bad, when I would be having a bad day myself, I would go to see Maurice, selfishly, to say, I want to get pumped up. And he never failed to pump me up.”

--Jack Twyman

|

The injury cast a pall over the Royals. Some of the players believed that the decision to fly ahead to Cincinnati and the resulting additional forty-five minutes of the flight contributed to the severity of Maurice's illness. And seeing how Maurice had been tossed aside by the new ownership, the players began to abandon the Royals. Center Clyde Lovellette didn't want to play on Cincinnati and forced a trade to St. Louis, where he'd go on to become an All-Star. Dick Ricketts gave up basketball altogether, to pitch for the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team. But the Royals franchise was saved from folding when Ben Kerner of the St. Louis Hawks, the Western Division champions, literally gave Cincinnati five players, no charge. In addition, he traded Wayne Embry to the Royals, giving Cincinnatti a new center. The fans, however, were less generous, averaging fifteen hundred admissions per game for the 1958-59 season. Relying on Twyman's jumpshot and little else, the Royals could only win 19 games and finished in last place.

Twyman was the team's highest-paid player -- he made $20,000 a year. But Stoke's annual medical costs were five times that amount (workmen's comp didn't pay for Stokes' medication, which was incredibly expensive). So Twyman worked tirelessly to raise more money. He convinced the NBA to stage a double-header in Cincinnati and give the after-tax profits to Stokes (roughly $10,000). He cut a deal with a Pennsylvania spaghetti sauce manufacturer to get its product into Cincinnati stores in exchange for the profits from the first 700 cases (the deal grossed Stokes' fund $4,700). Sportswriters across the country helped him by asking their readers to send checks for whatever they could afford. (Pageant reported that children sent pennies, one woman on Social Security sent five bucks and wrote, "He needs it more than me," and one man sent a hundred dollar check and the note, "Where but in the United States would you find a Jew sending money to a Catholic to help a Negro?") According to Wayne Embry in his autobiography, Twyman got a few checks, but also a lot of hate mail from racists "who could not understand how a white man could care for a black man. I always thought the letters strengthened Jack's resolve."

"Playing in the Stokes games was like being asked to play in an All-Star game. Everybody was there. To see every player offering their services at their own expense was really special. It wasn't like guys were making a lot of money. But it was so important to help a fraternity brother."

--Hall of Famer Billy Cunningham |

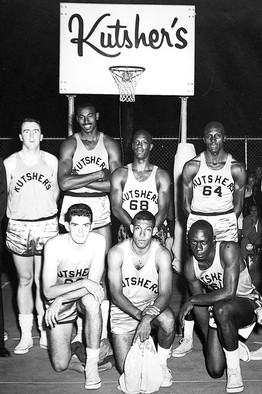

Wilt Chamberlain and other NBA players at the charity game. |

When the money ran out in 1958, Twyman organized an exhibition doubleheader at Kutsher's Country Club in Monticello, N.Y., and played a game that raised $10,000 to help pay Stokes' expenses. That game became an annual tradition. It was called The Maurice Stokes Game, and included many of the NBA players, like Russell, Embry, Oscar Robertson, Jerry Lucas, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Dr. J and Pistol Pete Maravich. Wilt Chamberlain even flew back from Paris one year, just to play. "It was serious basketball," said Mark Kutsher, whose father Milton turned the resort over for the game. "They had fun, too. I remember Johnny Kerr grabbing Wilt Chamberlain's shorts so he couldn't jump. Wilt said Kerr did the same thing in the regular season." In a wheelchair, Stokes even accompanied Twyman to some of the games. (The tradition continues to this day "to raise funds for needy former players from the game's earlier days." But per NBA and insurance company restrictions, after the year 2000 it became the Maurice Stokes/Wilt Chamberlain Celebrity Pro-Am Golf Tournament instead of an off-season basketball game.

"His mind was perfect. That was the sad thing about it: It was a perfect mind trapped in a paralyzed body. A week before he fell ill, he was one of the most spectacular athletes in the United States."

"His mind was perfect. That was the sad thing about it: It was a perfect mind trapped in a paralyzed body. A week before he fell ill, he was one of the most spectacular athletes in the United States."

--Jack Twyman

|

Stokes spent his final years at Good Samaritan Hospital. As his guardian, Twyman visited Stokes regularly. Others paid him tribute, as well: Future All-Star Chet Walker, who patterned his game after Stokes, was taken to visit his boyhood hero by his coach Art Hallum, Stokes' former teammate. Another visitor was former teammate Jack McMahon, by then a coach at Cincinnati. "Every time he'd see me he'd get such a laugh around his face because I had put on weight and he remembered me as a 180-pound basketball player," he recalled. "So each year I'm getting fatter. One time I saw him in the Catskills and I knew every time I saw him he was going to laugh. He said to me, 'It's amazing how far the human skin can stretch.'"

But possibly the biggest tribute to Maurice came when the Stokes Athletics Center on the campus of the Saint Francis University was named in his honor. St. Francis' president, Rev. Vincent Negherbon, asked Stokes, "Would you be willing to have our new field house named after you?" They had to wipe away the tears from underneath Stokes' glasses.

As his condition degenerated, the years of physical inactivity robbed him of the awesome muscle tone in his arms, legs, stomach, and especially his heart. On March 31, 1970, Maurice suffered a massive heart attack. A fighter to the end, he lingered until April 6, when he finally passed away at the age of 36. At his request, he was buried in a cemetery on the campus of Saint Francis University in Loretto, Cambria County, Pennsylvania -- the first layperson interred at the Franciscans' campus cemetery. In his will, Stokes left half of his estate to the school -- in honor of Jack Twyman, "without whose prolonged and arduous work no estate would be available for me to give."

“Stokes lived as a symbol of the best that a man is, despite the terrible things which can happen to him.”

--New York Post columnist Milton Gross |

Jack Twyman's successful basketball career had ended in 1966. He scored 15,840 points in his career, was named to the All-NBA Second Team in 1960 and 1962, and appeared in six NBA All-Star Games. His No. 27 jersey was retired and hung besides Stoke's number 12 in the rafters of the team's arena.

Maurice Stokes had largely been forgotten by Royals fans, having been replaced on the team by superstars like Robertson and Lucas. But Twyman never forgot, even after Maurice's death. He always knew Stokes was better than all of them. In 1982, Twyman was inducted into the basketball Hall of Fame. But he felt Maurice belonged there, and kept nominating his old teammate, trying to keep his memory alive. But that plan grew less likely with each passing year.

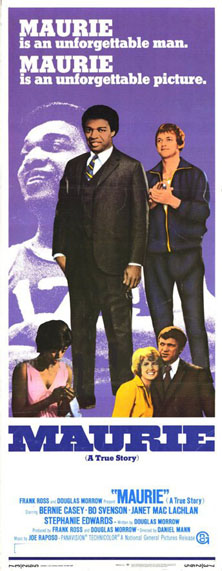

"MAURIE is a true story of human magnificence-- The magnificence of Maurice Stokes. A routine fall on a basketball court -- a week later, unable to move, to speak, to chew. Victim of a traumatic encephalopathy, Maurie was faced with medical doubt that he would ever swallow except through a siphon, much less speak, or write, or stand, even if he lived at all. But live he did, with a richness that endowed all who knew him. And, after a decade of intensely painful therapy that would have killed lesser men, stand he did -- to receive the tumultuous ovation of the crowd attending Jack Twyman Night at the Cincinnati Gardens in March 1966.”

--Promotional material for the film "Maurie" (1973) |

|

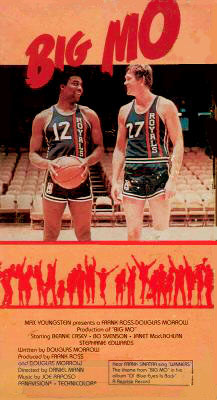

But just when the Hall of Fame stopped calling, Hollywood started. Maurice’s story was made into a film entitled Maurie in 1973 by National General Pictures. The filmmakers went all out, even recruiting Frank Sinatra to sing the theme song, "Winners" (Reprise 1190). The film is now called Big Mo on video (pictured at left).

The film starred then-newcomer Bernie Casey as Maurice, and Bo Svenson as Jack Twyman. (Hmmm, what's this? Jack Twyman is suddenly bigger than Big Mo? Hey, it's a movie -- go with it!) In addition to Casey and Svenson, the cast included Bill Walker and Maidie Norman as Maurice's parents; Janet MacLachlan played Stokes' college girlfriend, Dorothy (Stokes is carrying a diamond ring in his pocket, all set to propose to her, when he has the seizure on the plane); and Ji-Tu Cumbuka played Oscar Robertson, who has the most moving line in the film. In the scene, Dorothy is questioning Jack Twyman's motivations, how he can be so dedicated to Maurice. Oscar claims not to have thought about it. Then, the script reads...

| (still skeptical, looks at him) |

|

|

That beautiful line of dialog was scripted by writer/producer Douglas Morrow, who was a sort of "doomed sports figure movie" expert, having previously written Jim Thorpe, All-American for Burt Lancaster, and won an Oscar for writing The Stratton Story for Jimmy Stewart -- a film about a major league pitcher who lost a leg in a hunting accident but tried to continue playing pro ball. So he seemed the natural guy to tell the story of Maurice.

Star Bernie Casey was a Pro Bowl football player during the sixties, for the 49ers and Rams. He was 6’4” and weighed 215 pounds -– pretty impressive until you realize it made him three inches and twenty pounds lighter than the real Maurice... and an inch shorter than the actor playing Twyman! But Casey and Svenson have an easy chemistry as the two leads, and perform some nice scenes together: When Stokes is awarded a new car as Rookie of the Year, he doesn't know how to drive, so Jack chauffers him off the court -- and promptly to a used car dealership, where Stokes sells the car for cash. Another nice scene occurs when a wheelchair-bound Maurice finally returns to the Gardens to honor his friend on "Jack Twyman Night" and stands for the applauding crowd.

|

Maurie is a family film, so the proceedings are chaste -- Maurice and Dorothy have a fairly platonic relationship throughout his years in the NBA, and Stokes is drinking milk before the fateful plane flight instead of beer -- but the scenes of Maurice's painful therapy are grueling and moving to watch.

The film does have flaws: You never see Maurice at the height of his basketball abilities, so while the story is sad, you don't get the full impact of seeing Maurice's fall from athletic dominance to complete incapacity. Secondly, the tragic accident that ended Stokes' career happens before the story starts -- we are introduced to Maurice a few days later, against Detroit, feeling uneasy, missing passes and layups, and becoming ill. The accident itself is just mentioned in passing at the hospital, and is played off like an everyday occurance which in this case resulted in a freak reaction -- when we know that in reality, Stokes was knocked unconscious from the brutal fall, and had to be revived with smelling salts.

Sadly, Maurie wasn't successful with audiences or critics, and the original death scene climax was cut and replaced with a more upbeat ending. Here's the ending as written in the screenplay -- Jack has retired from basketball, and has just finished his color commentary for a Laker game on TV at the Forum in Los Angeles. Meanwhile, we have just witnessed Maurice pass away while watching the broadcast in his hospital room. So the film cuts to Jack, after the game at the Forum dealing with the news. Oscar Roberston appears, and we get a final shot straight out of the last scene from Casablanca:

| INT. LOS ANGELES FORUM - ARENA FLOOR - NIGHT | | | | |

| ANOTHER ANGLE - FROM BEHIND JACK - TOWARD ARENA FLOOR | | |

| CLOSE TWO SHOT - JACK & ROBERTSON | | |

| (a bare shake of Jack's head) |

| |

“He certainly belongs right here among the greatest of all time. This is a big deal. This is really the final and deserving tribute to an outstanding basketball player and a remarkable individual.”

--Jack Twyman |

Jack Twyman

(center)

hugs Oscar Robertson

(left) and Bob Pettit (right)

after accepting on behalf

of Stokes. |

But then Twyman concocted a real-life rewrite, and finally provided the happy postscript for his friend's life story that his movie character didn't: In September of 2004, Maurice Stokes was inducted into the Naismith International Basketball Hall of Fame, 44 years after he played in his last, tragic game, in which he somehow pulled down 15 rebounds before slipping into a coma. "It's not a sentimental selection, not at all," Twyman said. "I've long said that Maurice was worthy of the Hall of Fame. His college record certainly establishes him," Twyman told the Cincinnati Post. "He was a guard-center-forward who rebounded, led the fast break, and was the first multi-purpose player ever in the game, I think. He was the first player to have the versatility that's pretty common these days."

Twyman accepted on Stokes’ behalf, with Oscar Robertson present for this ending -- the real Oscar, not Ji-Tu Cumbuka! Twyman also brought his children and grandchildren to Springfield for the ceremonies. "They grew up with Maurice. He was part of our family."

Bob Pettit introduced Stokes, at Twyman's request, and Jack came onstage to accept for his friend. His voice cracked with emotion as he said, "Whatever I've done for Maurice, I've gained tenfold. Let me just say, congratulations big fella, you made it." Twyman was presented with Stokes’ Hall of Fame jacket, ring and trophy. He gave these items to Saint Francis, for permanent display at the Maurice Stokes Athletics Center.

So MVP awards, scoring and rebounding titles, NBA Championships, million-dollar contracts, endorsement deals, and even Academy Awards may have cruelly eluded Maurice Stokes, but now the man who was called "Magic Johnson before there was Magic Johnson," and "Karl Malone with more finesse" waits for those basketball greats to follow him into the Hall of Fame... just the way Jack Twyman knew it should be. "What happened to Maurice put everything in perspective for me. If people want to remember me for that and not what I did on the court, that doesn't bother me at all."

John Kennedy "Jack" Twyman (Smokey)

Position: F-G

Height: 6'6" Weight: 210 lbs.

Born: May 11, 1934 in Pittsburgh, PA

High School: Central Catholic in Pittsburgh, PA

College: University of Cincinnati

Scored 1,598 points and finished his career as Cincinnati's scoring leader. In the NBA, he played his entire eleven-year era with Rochester/Cincinnati and averaged 31.2 points a game in 1959-60.

Six-time NBA All-Star, 1957-60, 1962-63

Second Team All-NBA, 1960, 1962

Among the NBA's top fifteen scorers for eight seasons

Number retired by the Sacramento Kings

Inducted into the Naismith International Basketball Hall of Fame in 1982.

|

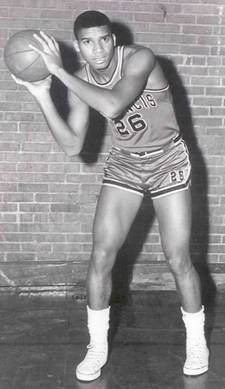

Maurice Stokes (Mo)

Position: F

Height: 6' 7'' Weight: 232

Born: 6/17/1933, in Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Died: 4/6/1970

High School: George Westinghouse, in Pittsburgh, PA

College: Saint Francis University

Inducted into the Saint Francis University Athletics Hall of Fame in 1996, and his uniform number 26 was retired by the school in 2000 (he currently ranks first all-time at SFU in rebounding and second in scoring).

Named to the NAIA Basketball Hall of Fame in 1964.

In 1997, voted to the All–NIT team by a media panel, the only player on a 4th-place team to be so honored.

Number retired by the Sacramento Kings

Inducted into the Naismith International Basketball Hall of Fame in 2004. And it was about friggin' time.

|

|

Sources

|

I Woke Up Helpless, by Maurice Stokes, with Harry T. Paxton. From the 'Saturday Evening Post,' March 14, 1959. Stokes tells his story -- sort of. Click on title to read the full article. |

- Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game, by Oscar Robertson. 342 pages. Publisher: Rodale Books (November 15, 2003).

- Sky Kings: Black Pioneers of Professional Basketball, by Bijan C. Bayne. Publisher: Franklin Watts Publ. (1997).

- They Cleared the Lane: The NBA's Black Pioneers, by Ron Thomas. Publisher: University of Nebraska Press (May 1, 2002).

- Cincinnati Hoops, by Kevin Grace. Pages 68, 69: Maurice Stokes. Publisher: Arcadia Publishing (November 17, 2003).

- Cincinnati Revealed: A Photographic History of the Queen City, by Kevin Grace, Tom White. Page 86: Maurice Stokes. Publisher: Arcadia Publishing.

- The Inside Game: Race, Power, and Politics in the NBA, by Wayne Embry, Mary Schmitt Boyer, and Spike Lee. Page 94-96. Publisher: University of Akron Press (May 1, 2004).

- Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh, by Rob Ruck. Publisher: University of Illinois Press (June 1, 1993).

- Cincinnati on Field and Court: The Sports Legacy of the Queen City, by Kevin Grace. Published by Arcadia Publishing (October 21, 2002).

- Stokes-Twyman story was saga of brotherhood, by Sean Keeler, Cincinnati Post. Publication date: 04-13-99.

- Stokes game: Players bonding to help their own, by Hal Bock, Associated Press (in the Topeka Capital-Journal). Publication date: 8/4/2004.

- Maurice Stokes - The Glory and Tragedy of the NBA's First Black Superstar, by Tim Adams, X9 Sports. Publication date: August 25, 2006.

- ESPN Sportscentury: Stokes' life a tale of tragedy and friendship, by Bob Carter, ESPN. Publication date: 09/13/2004.

- Teammates: Hall of Famer Jack Twyman keeps the memory of a fallen friend alive, by Frank Deford, SI.com. Publication date: September 1, 2004.

- St. Francis (PA)'s Maurice Stokes Inducted into Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, by NEC, the Official Site of the Northeast Conference. Publication date: 9/10/2004.

- Royals History: The Royals Move to the Queen City.

- Extreme Generosity, by Rev. Dr. Robert R. Hansel, Explorefaith.org. Publication date: September 7, 2003.

- Labor of love assures memory of Stokes lives on, by Chuck Finder, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Publication date: April 11, 2004.

- At long last, Stokes in Hall of Fame, by Chuck Finder, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Publication date: September 11, 2004.

- Twyman lauds election of star-crossed teammate Stokes, by Dustin Dow, Cincinnati Enquirer. Publication date: April 6, 2004.

- Stokes was special: Royals teammates shared friendship, by Lonnie Wheeler, Cincinnati Post. Publication date: 02-19-2004.

- Stokes lauded as Hall of Fame induction nears, by Dave Mackall, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Publication date: Thursday, April 8, 2004.

- Saint Francis University, the official website.

- Civil Rights in Pittsburgh: Timeline 1800's - 1960, from the Freedom Corner Monument website.

- Chuck Cooper, a biography.

- Rochester Royals, at Sports E-Cyclopedia; Stats researched by Frank Fleming. Publication date: February 19, 2003.

- Stokes Legend Grows. Saint Francis University Magazine – Summer 2004.

- The Tragedy of Maurice Stokes, SPORT Magazine, February, 1959.

- His Brother's Keeper: The story of Maurice Stokes and Jack Twyman, by Al Silverman. 'Pageant,' May 1960; Vol 15, No 11.

- Maurice Stokes ten years after accident. 'Sports Illustrated,' March 25, 1968.

- Maurice Stokes page on the official Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame website.

- John K. "Jack" Twyman page on the official Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame website.

- Maurice Stokes Obituary in TIME Magazine, Monday, April 20, 1970.

- Find A Grave Internet Memorial.

|

|

|