| Saturday Evening Post, March 14, 1959

Vol. 231, No. 37 I Woke Up Helpless By Maurice Stokes

with Harry T. Paxton From his hospital bed the Cincinnati Royals' courageous star tells off the determined battle he is waging to overcome the basketball injury that left him totally paralyzed. |

| About Maurice Stokes A year ago this week sports fans were stunned to read that big Maurice Stokes, one of the stars of the National Basketball Association, had collapsed mysteriously from what was thought to be a brain infection. For a long time thereafter, news bulletins conveyed the impression that Stokes might never regain consciousness.

But he did come out of his coma. Since then Stokes has been determinedly fighting his way back from a state of total paralysis. It is as remarkable a performance as any he ever gave us in basketball, where he was an all-around standout.

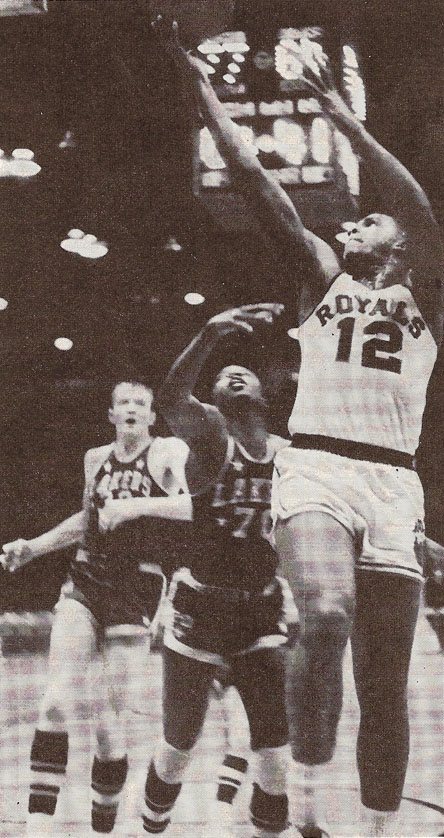

As a senior at St. Francis College, of Loretto, Pennsylvania, Stokes was chosen as the most valuable player in the 1955 National Invitation Tournament. He was N.B.A. rookie the next year with the Rochester Royals—now the Cincinnati Royals. Stokes made the N.B.A. All-Star squad every year he was in the league. In his last season he was not only among the top fifteen scorers in average points per game (16.9) but also second in rebounds (18.1) and third in assists (6.4).

THE EDITORS |

One day last year I woke up for a few minutes from the longest sleep of my life. I opened my eyes and saw three people near my bed. I recognized my sister, my father and my old friend, Ed Fleming, of the Minneapolis Lakers, who played basketball with me at Westinghouse High in Pittsburgh and then in the pro league. I started to say hello—and found I couldn't talk. I couldn't even move.

I have to admit it was a shock to wake up and find myself in such a helpless condition. Not being able to move was the worst. It was almost like being buried alive. As I lay there looking up at those people, unable to communicate with them in any way, I had the feeling I was cut off from the world. Tears started coming to my eyes.

I knew I was in a hospital. I could remember collapsing on a plane trip and being brought to the hospital and being worked on by the doctors. After that there was a blank. I came out of it briefly from time to time—this first occasion was only three days after my collapse—but for weeks I was seldom more than semiconscious. The doctors thought I might have encephalitis—or sleeping sickness, as some people call it.

Well, when I first began to revive, I may have felt a little depressed at times, but I stopped being sorry for myself long ago. Today I have so much to be grateful for. I'm not cut off from people any more. I have many old friends and new ones who have been helping me. My mind was not affected by this thing, for which I thank the Lord, and I am beginning to get back the use of my body. I have already regained some of my movement.

When I think of the progress I've made in the year since this hit me, I know it will be only a matter of time until I recover completely. It is slow. It will take a lot of work on my part. But I don't mind that. One of these days I'll be leaving this hospital on my own feet. I'll be back playing basketball with the Cincinnati Royals.

As for talking, I am having to learn how to speak all over again. This also takes time. I can't pronounce many words properly yet. However, I am able to have conversations. I can answer questions, and I can spell out the things I want to say.

In preparing this article, my collaborator started out by getting as much information as he could from other people, to save me the trouble of spelling out every last detail. Then he sat down and checked everything with me. I straightened him out on a number of points and added some new ones—especially about the thoughts that were in my mind at different stages. Now this is my own story, told in my own kind of language. I have gone over it word by word.

Lying around like this has been a new experience for me. I'm a pretty husky fellow—six feet seven, with a playing weight of 235 to 240 pounds—and I've been active all my life. I'm not used to being sick. I had no idea this breakdown was coming on until a few minutes before it happened.

I remember the whole day very clearly. It was March fifteenth of last year. The regular schedule in the National Basketball Association had ended, and the postseason play-offs were beginning. We were in Detroit to open a series against the Pistons that afternoon. This was the first time we had qualified for the playoffs in my three years with the Royals. We had tied with Detroit for second place in the Western Division during the league season, and we thought we had a chance to go all the way in the playoffs.

Three days before, in our last regular season game, I had taken a pretty hard bump. We were playing the Lakers in Minneapolis. Going up for a rebound, I got knocked off balance and went down and banged my head on the floor. I was dazed for a couple of minutes. But when I revived I felt all right, and I kept on playing. We beat the Lakers, 96-89, and I was the Royals' high scorer, with twenty-four points.

December, 1957: Maurice (No. 12) in action against Minneapolis, three months before he was stricken. |

I didn't think anything more about that bump on the head. By the time we got to Detroit for our opening play-off game, the only thing that was bothering me physically was a large boil underneath my chin. This had nothing to do with what happened later.

The morning of the game we slept late and had a big breakfast in the coffee shop of our hotel, the Sheraton-Cadillac. Then we relaxed in our rooms until it was time to go out to the University of Detroit field house for the game.

The less said about the game, the better. We lost it, 100-83. It wasn't a very good afternoon for our team, and it certainly wasn't a good one for me. I scored only twelve points, although I got fifteen rebounds. But I wasn't sick or anything like that. I still felt O.K. In the locker room afterward I was going around saying, "Well, that's one by the boards. Let's forget about it and start thinking about how we're going to lick them in Cincinnati tomorrow."

We were flying back to Cincinnati around 9:30 that night, which left us several hours to kill. We took cabs back to our hotel, and then everybody went across the street to the steak house.

It takes nearly an hour to get from downtown Detroit to the Willow Run Airport, so we boarded the airport bus around seven-thirty or quarter to eight. About halfway out my stomach started to bother me. I felt like I was going to be sick. I asked if someone would take my bags for me when we got to the airport. Jack Twyman took my luggage, while Dick Ricketts went with me to the men's room.

I came out feeling quite a bit better, but while we were waiting for our flight to be announced, I had to go back and be sick again. I believe the same thing happened a third time. At this point some of the fellows were suggesting that I spend the night in Detroit and see a doctor and then come on to Cincinnati the next morning. But we only had about an hour-and-a-quarter flight ahead of us. I figured I could stick it out until we got to Cincinnati, and then if I needed help I could call Dr. Ben Hawkins, who serves as the Royals' team physician.

In another few minutes we boarded the plane. The fellows had me take a sea in the rear. Jack Twyman sat in front of me, and Dick Ricketts sat alongside me. I'd had many a dinner with Dick and his wife at their apartment in Cincinnati that season. I'm a bachelor myself.

Anyway, I still didn't think there was anything more wrong with than a badly upset stomach. Everybody else thought the same. But I was beginning to feel bad all over. All of a sudden I reached out without meaning to and clutched Dick Ricketts by the leg. I said, "Dick, every bone in my body aches me. I feel like I'm going to die."

Sweat was pouring out of me. I was having difficulty breathing. I more or less collapsed. The others thought I had passed out completely, but I was still conscious. I was aware of what was taking place.

My teammates were doing everything they could think of to help me. The Trans World Airlines stewardess, Miss Jeanne Phillips, pitched in with them. They stretched me across the back seat. They covered me with blankets. They put cold compresses on my forehead and neck. My breathing was so labored by now—my throat was choking up with saliva and mucus—that they got me an oxygen mask.

One other very important thing was done on the plane. You see, I was planning to become a Catholic. I got interested in the religion back when I was at St. Francis College, a Catholic school in Loretto, Pennsylvania. Since then I had attended Mass from time to time. I had gone several times recently with two of my Catholic teammates, Richie Regan and Jack Twyman, and I had told them I wanted to join the church.

Well, in an emergency situation, where a person who has expressed the desire to become a Catholic might not live long enough to go through the regular baptismal procedure, he can be baptized by a layman. Richie Regan did this as I lay there helpless on the plane. A little later I was baptized again by a priest at the hospital. It has been a great comfort to me all these months to know that I have pledged myself to God.

Meanwhile, the airliner captain radioed ahead to have an ambulance meet us at the Greater Cincinnati Airport at Covington, Kentucky. When we landed, the ambulance had already arrived from Saint Elizabeth Hospital in Covington. I remember being carried off the plane by the fellows—it took about six of them—and then being wheeled into the ambulance. I was soaked through with sweat. Some of the fellows have told me that I couldn't have been any wetter if I'd fallen into a swimming pool with my clothes on.

At the hospital two interns went right to work on me. They kept on with the oxygen, and they began giving me intravenous feeding. Pretty soon the team physician, Doctor Hawkins, showed up. Les Harrison, who was then the president of the Royals, had phoned him. Dr. Curwood R. Hunter came along soon after. He was called in by the hospital. Dr. Melvin Steves also came.

Then there was the Catholic priest who baptized me—Father Aldo, of Sacred Heart. He happened to be at the hospital that night. The next morning the regular hospital priest, Father Erwin, gave me the last rites of the church.

I remember that the doctors mad some tests the night I was brought in and that they performed a tracheotomy. This means that they cut an opening in my throat and inserted an air tube directly into my windpipe to make sure that I wouldn't suffocate. Then I remember them phoning my mother in Pittsburgh. After that I went into my long sleep.

Mrs. Elizabeth Ross, one of my nurses at St. Elizabeth's, says that from my very first day there were periods when my eyes seemed to follow her around the room. I don't remember that. I didn't know that my mother and my twin sister, Claurice, had arrived from Pittsburgh a few hours after my collapse or that my older brother, Master Sgt. Tero Stokes, Jr., had come down on emergency furlough from the Bunker Hill Air Force Base in Indiana. There were many things I didn't find out for a while.

I know now that the main problem at first was just to keep me alive. My heart was working, and I was breathing, and that was about all. I was being fed intravenously. From time to time the breathing tube in my throat would get clogged and have to be cleared out. My position in bed had to be shifted every couple of hours to keep me from getting bedsores. At one point I was running high temperatures, and as many as fifteen icebags had to e kept on me to bring the fever down.

All this meant plenty of work for Mrs. Ross and the other nurses who attended me at St. Elizabeth's, including Miss Stella Collins. I can never thank them enough. That goes for the whole of Saint Elizabeth Hospital.

Members of my family were in there giving the nurses all the help they could. My brother—I call him Buster—came when he was needed most. My mother stayed on in Cincinnati for four solid months. My sister was there almost continuously too. Sis has two small children of her own back in Pittsburgh—she's Mrs. James Washington—but she gave me practically all her time. I want to thank her husband for making this possible. Mother and Sis stayed in my apartment in the Avondale section of Cincinnati and generally came to the hospital in shifts.

As I mentioned before, the preliminary diagnosis by the doctors was that I had encephalitis. His is an inflammation of the brain caused by a virus. The doctors sent blood samples right away to the United States Public Health Service in Louisville for testing. The tests were negative, and so further specimens were requested. No virus showed up the second time either.

All this took a number of weeks. Since then the doctors have traced my trouble to that very hard bang on the head I got in Minneapolis. It caused a swelling in the brain, and this brought on the unconsciousness and the paralysis. In medical language, Doctor Hawkins and Doctor Hunter say that I had a post-traumatic encephalopathy.

Well, he swelling inside my head began to go down. I've told how I came back to consciousness for the first time on a day when Ed Fleming was in the room as a visitor, along with my father and sister. In the weeks that followed I woke up more and more often. I soon became aware of various other people.

My father couldn't get to Cincinnati as early or as often as my mother and sister. He had to go on earning an income at the Eager Thomas Steel Company in Braddock, Pennsylvania, where he has worked for thirty-three years. It increased the family expenses to have my mother spending so much time in Cincinnati. But he has come to see me himself whenever he could possibly manage it. It's a great thing to have a family like mine to stand by you in a time of trouble. They have spared no cost or effort to be at my side. One or another of them still makes the trip to Cincinnati at least once or twice every month.

The basketball season ended for the Cincinnati Royals right after I went into the hospital—they got eliminated from the play-offs by the Detroit Pistons the next night. Most of the fellows had to go back to their homes in other parts of the country. Jack Twyman was an exception. He came from Pittsburgh originally—I used to play with him in a summer league there—but now he lives right here in Cincinnati. He dropped in on me almost every day. Even during the basketball season, when he travels so much and has so little spare time, he still comes around to see me whenever he's home. Jack's name certainly belongs high on the long list of people to whom I owe thanks.

One problem that came up early was a financial one. This has now been solved for the time being, because my medical bills are being paid by Ohio workmen's compensation, but at the beginning nobody could be sure how my expenses would be met. I had about $9000 in the bank, but I was in no condition to get at it, of course. Somebody had to be empowered to draw on that money for me if I needed it. Under the laws of Ohio, where I had my home, this had to be done by a resident of the state. So Jack Twyman volunteered. In April the probate court in Cincinnati appointed him my legal guardian.

My unconsciousness was lifting by then, but I was still completely helpless. I had some movement around my eyes—they could tell by my expression when the icebags or something else was making me uncomfortable, for instance—but there was no movement at all in my body. My body wasn't lifeless, though. The doctors found this out by sticking pins in me at different places. I could feel those pins all right, and I'd wince.

I could hear people when they talked, and I knew what they were saying. I could understand them a lot better than they could understand me. There was so little I could do to express myself. My speech muscles just weren't working. Eventually I progressed to where I could answer questions by signaling "yes" or "no" with my eyes. People who were around me a lot, like my family and Mrs. Ross, sometimes could practically read my mind by looking at me.

I lost a great deal of weight in the early stages. Nobody put me on a scale, naturally, but I may have dropped from about 235 pounds to as little as 170 or 160. As my condition improved, the weight started to come back. I believe it's all the way back by now.

At first I only had intravenous feeding. After a couple of weeks they began supplementing this with direct feeding through a tube down my nose into my stomach. In a few more weeks, as my digestive system became stronger, they gave up the intravenous feeding altogether.

Meanwhile, they started getting me back to normal eating. They had to teach me how to swallow again and then how to chew. This served a double purpose. You have to master swallowing and chewing before you can learn how to talk, which is one of the projects I'm working on right now.

Well, they began by squirting small amounts of liquid in my mouth. At first I couldn't swallow at all, but on April twenty-first I took my first liquid by mouth. Next came soft foods—things like gelatin and cereal and mashed potatoes and custard—to give me some practice in chewing again. After that I went to ground meat and then to meat cut up in small pieces. All this time the tracheotomy tube was still in my throat for breathing, but by June twenty-first that had come out, and I also was eating the regular hospital meals.

These simple actions don't come back to you very fast. It's the same with all he muscles in my body that I lost contact with for so long. After I began feeling better, Mrs. Ross, the nurse, started exercising some of my muscles for me. At first she'd just take each finger and bend it four or five times. Then she'd take the whole hand and open and close it. Her next step was to close the hand on a piece of foam rubber and tell me to grip on it so that it wouldn't pop out. After a while I was able to hold it for a few seconds. Mrs. Ross moved on from there to manipulating my arms. A regular physical therapist at St. Elizabeth's, Miss Aurora Lyons, also began working with me.

My life was getting more normal in every way. I was listening to the radio and catching up on the news. Letters from basketball fans had been coming to the hospital for me by the hundreds, and I had the letters read to me. It gave me a good feeling to know that so many people on the outside were rooting for me.

The doctors were very pleased at the way I was coming along. They decided it was time I moved to a place that was equipped to give me complete physical therapy. So on July twenty-fifth, after 133 days at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Covington, I was transferred across the Ohio River to Christ Hospital in Cincinnati. I hated to leave the people at Saint Elizabeth's, because they were so wonderful to me there. But they've been just as wonderful to me here in Christ Hospital.

Anyway, that move was an exciting thing for me. Although my bed had been pushed onto the sun porch now and then at Saint Elizabeth's, this was the first time I'd really been out of doors. They loaded me into an ambulance. I kept looking out the windows to see as much as I could.

My sister and Jack Twyman were in the ambulance with me. Jack was kidding me, the way my buddies usually do, but when we arrived at Christ Hospital, he turned serious. He said, "Well, sport, this is it. This is the last time you're going to see daylight until you walk out of this place under your own power."

More than seven months have passed since then, and it may be a number of months before I do walk out, but I am going to make it. In the meantime, I can assure you that I'm not bored. I'm used to hard work. When I was a kid, I sold newspapers, and I took other jobs to pick up money in my spare time—washing windows for people, and things like that. But I've never been any busier in my life than I am here at Christ Hospital.

Just about every minute of the day is filled from the time I wake up, which is generally between 7:15 and 7:30. Miss Carolyn Davis, the nurse who takes care of me from seven A.M. to three P.M., says that I always wake up with a nice smile on my face. Anyway, she greets me with a glass of prune juice and a couple of vitamin pills and checks my blood pressure. Then she washes my face for me and brushes my teeth—I haven't got quite enough movement in my hands yet to handle this myself. Next she gives me something like a carrot or a piece of celery to chew on. This isn't for nourishment. It's part of my speech therapy, to strengthen my throat muscles. I munch like that at odd hours during the day.

Around eight o'clock breakfast comes in. The nurse feeds it to me. I have fruit, cereal, eggs or whatever else is on the menu that morning. I also have four eight-ounce glasses of liquids—milk, chocolate milk shake, orange juice and water. They want me to have plenty of fluid, to keep my kidneys and bladder in good condition. I spend an hour or so at breakfast; my chewing and swallowing are still a little slow.

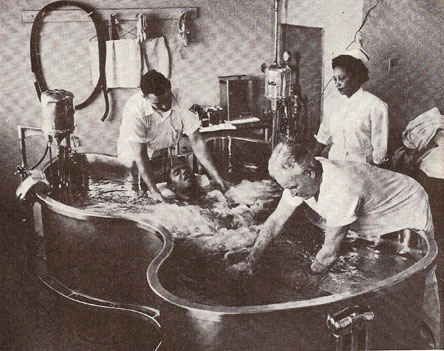

I've hardly finished breakfast before I'm riding the elevator up to the physical therapy room on the tenth floor. There I go into a Hubbard tank. This is a big stainless-steel tub filled with warm water. Tom Cutcher, the physical therapist, and his orderlies put me on a special stretcher, and a hoist lifts it up over the tank. I am lowered into the water up to my neck. There's a pillow to support my head.

At Christ Hospital, Cincinnati, Stokes is exercised daily in a hydrotherapy machine called a Hubbard tank. |

In the Hubbard tank I am given hydrotherapy—there's a propeller in there to swirl the water round, like a whirlpool bath. Then Tom Cutcher gives me underwater exercise. He takes each joint and exercises it to maintain its full movement, and he stretches my muscles to keep them from getting tight. These are called passive exercises. However, I'm supposed to enter into it by pulling and pushing against him whenever I can. Then there are active exercises, in which I'm supposed to do all the work. I can bend my arms all the way back at the elbows now and use my shoulders some. There also have been some stirrings of movement in my legs.

My morning physical therapy lasts a good two hours. It may be 11:15 or even 11:30 before I'm back in my room. The nurse gives me some pills and either a partial bath or a whole bath, depending on how much time is left before lunch is served at noon. I eat a big lunch—meat, vegetables, salad and dessert. Sometimes I have steak. A while back I asked Jack Twyman if he couldn't get me some New York cut sirloins, and now they're serving me steak three or four times a week.

About 1:30 I go back up for more physical therapy. In the afternoon they give me electrical stimulation in my thighs and in my arms. This is to contract the muscles and keep up the muscle tone. Then Tom Cutcher puts me through some more exercises—especially restive exercises, where I'm working against him to strengthen my muscles.

Well, I've played a lot of hard basketball over the years. I've always tried to bear down in competition. But I've never had to put out quite as hard as I do in this exercising. In a way, this is competition too. It's more important than ever for me to win.

Another thing they do in the afternoon is to get me on a tilt table. When you've been lying flat for months, it makes you dizzy to switch to a vertical position. So they put you on this table and tilt you up in gradual stages, to get you used to being upright again.

In late January I graduated to sitting up in a chair. The first time I sat for fifteen minutes, and the periods have increased since then. I also have begun sitting on the edge of a table, with some help from Tom Cutcher.

My afternoon physical therapy takes two hours or more. Incidentally, I supplement this with some work in my own room, using an exercise bar over my bed. Anyway, I return to the room between 3:30 and four. By this time Mrs. Lillian Sampler has come on duty as my nurse. She is there from three P.M. to eleven P.M. Then Miss Eleanor Jones takes over until seven in the morning, when Miss Davis comes back.

I'll need this twenty-four-hour care for a while yet, since I still have to be helped on many things. I am very fortunate in my nurses. They are three mighty fine women.

I get a breathing spell around dinner, which is served around five. If I don't have a visitor, I may listen to news and music on my bedside radio or watch the TV set in my room or catch up on some of my mail. I can do my own reading now. The nurse just puts on my reading glasses—I've worn them since I was a kid—and props the letters up in front of me. It's the same thing with the sports page of my daily newspaper.

After dinner, Mrs. Mary Helen Sponzilli, a speech therapist from the Cincinnati Speech and Hearing Center, spends an hour with me. You don't realize how complicated talking is until you have to learn it from the ground up. Mrs. Sponzilli started off with things like showing me how to hold my lips to say certain letters and having me blow out matches to increase my diaphragm control. She's giving me tongue exercises now, and so forth. The general idea is to retrain me in the "feel" and sound of speech.

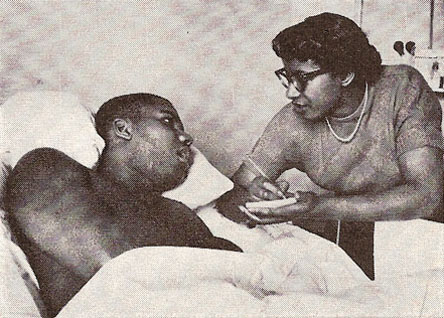

I can handle a few simple words fairly well by this time, but I have some distance to go yet before I'm really talking again. However, this doesn't keep me from having conversations. I can urn my head from side to side now or nod it up and down. That makes it easy for me to answer questions.

If I want to "say" something more than "yes" or "no," I indicate this by a shake of my head. Then the other person takes a pad and pencil and starts reciting the alphabet letter by letter. Each time he hits the right letter, I nod. That way I can spell out words. I've been doing this since the early months, when I was still at St. Elizabeth's.

Stokes, who lost his speech, spells out words to his sister Claurice by moving his head as she recites the alphabet. |

Often the other person can tell what word I have in mind after a couple of letters, or figure out the whole sentence from a word or two. For example, Pepper Wilson, the general manager of the Royals, was visiting me one day last summer, and he mentioned that Jimmy McClellan, a friend of mine from St. Francis College, was going to try out with the Royals in the fall.

I signaled that I wanted to make a comment, and then I spelled out the word "army."

"You mean you think McClellan may have to go into military service?" Pepper Wilson said.

I nodded.

"No, I don't think so," Wilson told me. "I've checked into that, and I believe he'll be able to play out the season with us if he makes the club." Unfortunately, he wound up being dropped. That isn't my point here, of course. I just want to show how much conversation can sometimes be developed out of a single word.

One sound I've been able to make very distinctly from the time I recovered consciousness is laughing. I get my share of laughs. The buddies who visit are forever cracking jokes. Often the jokes will be aimed at me. They'll say such things as, "Where have you been lately?" or "Come on, let's go for a walk." I get a kick out of all this. It's their way of telling me that I'm not a chronic invalid, but just a fellow who happened to get laid low for a while.

The doctors won't let me have too many visitors, because among other things, I have such a busy schedule here at Christ Hospital. I usually go to sleep by 9:30.

That's the program on weekdays. Weekends are my time for relaxation. I enjoy a lot of television, especially the Westerns and the sports broadcasts. The program I've looked forward to most of all, of course, has been the National Basketball Association game of the week on Sunday afternoons.

I've been indebted to the N.B.A. in a very personal way. Last October the league sponsored a benefit double-header for me in Cincinnati. The entire receipts after taxes—some $10,121.40—were turned over to me. The new owners of the Royals, headed by Thomas E. Wood, didn't deduct a penny for their expenses and neither did the three visiting teams—the St. Louis Hawks, the Boston Celtics and the Detroit Pistons.

As I explained earlier, money is no serious problem for the time being, because while I am hospitalized, my food, clothing and shelter are all included in the hospital expenses being paid for by Ohio workmen's compensation. However, as Jack Twyman, who is looking after my affairs as my legal guardian, has foreseen, when I leave the hospital I will have all of my personal expenses to pay, plus some extra services that I will have to buy. These things may eat up my funds before I begin to support myself again.

How I hope that it won't be very long after I get out of here before I'm strong enough to go back to the Royals! They have had their troubles in the N.B.A. this season, although they started to come along in January. I believe I could help them.

Basketball has been the biggest thing in my life since I was a little boy. It was responsible for me getting a college education. Ten colleges offered me scholarships. I'm glad I chose St. Francis, I haven't forgotten my years there, and the school hasn't forgotten me.

My fraternity brothers at Tau Kappa Epsilon have been pulling for me. The Franciscan fathers have said prayers for me and sent me Mass cards and scapulars. Coach W. T. Hughes and the entire St. Francis basketball squad visited me in the hospital twice when they were in Cincinnati to play Xavier last month. It was Coach Hughes and my high-school coach, Willard Fisher, who did the most to teach me basketball.

I'm grateful to every single person I've named in this article, and o many others I haven't mentioned. There's Father Scanlon, of Holy Name, who comes to see me and pray with me at Christ Hospital; Bill Nettles, my barber before I got sick, who keeps cutting my hair out of friendship; my buddy, Winston Brown, who does so many personal things for me; my cousin, Jane, in Cincinnati, and Mrs. Hicks, my aunt in Montclair, New Jersey. Then there are all of the professional baseball and basketball men who have visited me when they were in town.

I wish there were room to list everybody I'd like to thank. That includes he more than 5000 warmhearted strangers who have written me get-well letters. I intend to answer them all just as soon as I can. Some of these good people have even enclosed money—a total of about $2500.

It has been particularly inspiring to me to read sympathetic letters from people who had the same sort of trouble as mine. Generally their progress was slower than mine has been, but they recovered completely. I know I can do it too. I'm only twenty-five years old. I've got a lot of living ahead of me.

|