|

The story of this film is a long and tangled one, dating back to the 1950s.[1] The film has had a mixed reception among critics: Roger Ebert called it "possibly the most indulgent film ever made". Andrea LeVasseur called it "a psychedelic, absurd masterpiece"[2]; cinema historian Robert von Dassanowsky described it as "the anti-auteur work of all time."[3] Later drafts see vice made central to the plot, with the Le Chiffre character becoming head of a network of brothels whose patrons are then blackmailed by Le Chiffre to fund SPECTRE. The racy plot elements opened up by this change of background include a chase scene through Hamburg's red light district that results in Bond escaping whilst disguised as a lesbian mud wrestler. New characters appear such as Lili Wing, a brothel madam and former lover of Bond whose ultimate fate is to be crushed in the back of a garbage truck, and Gita, wife of Le Chiffre. The beautiful Gita, whose face and throat are hideously disfigured as a result of Bond using her as a shield during a gunfight in the same sequence which sees Wing meet her fate, goes on to become the prime protagonist in the torture scene that features in the book, a role originally Le Chiffre's.[7] Hecht never produced his final script though, dying of a heart attack two days before he was due to present it to Feldman in April 1964. Time reported in 1966 that the script had been completely re-written by Billy Wilder, and by the time the film reached production almost nothing of Hecht's screenplay remained. The one thing that did endure, and indeed became a key plot device of the finished film, was the idea of the name "James Bond" being given to a number of other agents. In the case of Hecht's version, this occurs after the demise of the original James Bond (an event which happened prior to the beginning of his story) which, as Hecht's M puts it, "not only perpetuates his memory, but confuses the opposition."[7] The producer, Charles K. Feldman, then planned to co-produce the film with United Artists' "official" Bond producers, Broccoli and Saltzman, who seriously considered the offer, if only to keep a rival Bond project from competing with their films. But after Broccoli and Saltzman lost a good part of their Thunderball profits to co-producer Kevin McClory (the man who owned the rights to the book for that film in a legal settlement with Ian Fleming), they eventually declined the offer. Pressing on, Feldman then hired Wolf Mankowitz (who several years earlier had been fired from the first EON film, Dr. No, for making the title villain in his script a monkey), who wrote a taught spy script (some actually attribute this draft to legendary screenwriter Ben Hecht, who wrote Hitchcock's Notorious). Feldman then tried to hire Connery away from EON to star as Bond, because his contract was almost up. But the star was deemed too expensive, so Feldman decided to star a British actor often compared to Connery, named Terence Cooper (pictured at right in the finished film, with Barbara Bouchet as Moneypenny). But the filmmakers discovered the book was almost impossible to adapt because EON had already used most of the scenes and situations in their films, and the project fell apart. Believing that he could not compete with the Eon series, Feldman resolved to produce the film as a satire.[1]

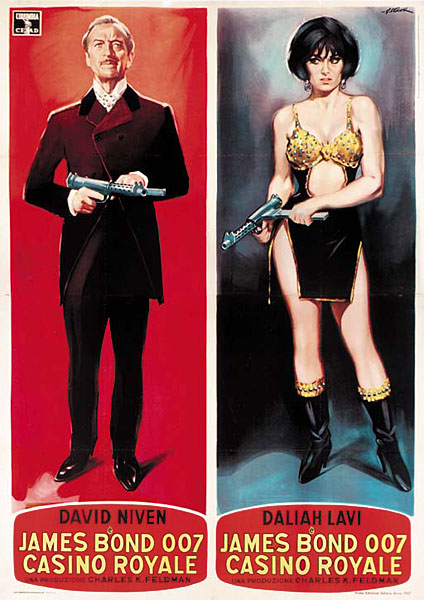

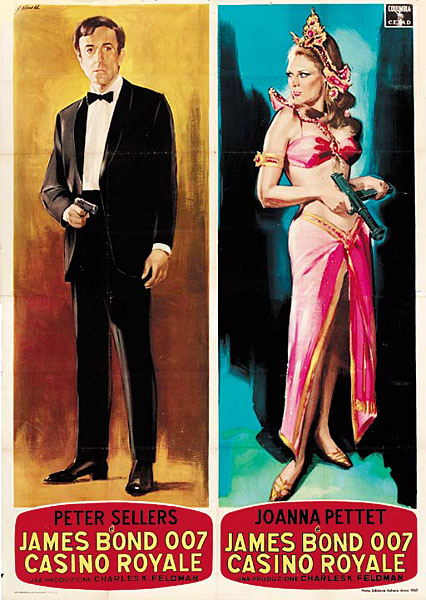

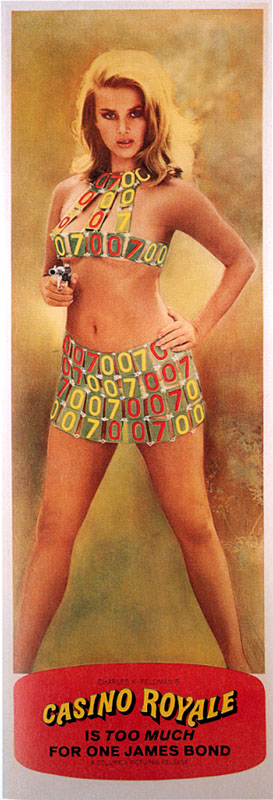

But director Joe McGrath then began to add wild comedy elements, and the film soon became more of a spoof. Sellers had no desire to compete with Connery. Instead, he became enamored with the idea of playing a card expert hired to impersonate James Bond. The film became a story about Peter Sellers' character, "Evelyn Tremble" (actually a very Bondian name in a nerdy sort of way), whom is the author of a "how-to" book on winning bacarrat. Tremble is hired by the British government to portray James Bond and bankrupt a Russian agent named Le Chiffre (Orson Welles) at the gambling tables of Casino Royale. Peter Sellers hired Terry Southern to write his dialogue (and not the rest of the script) in order to "outshine" Orson Welles and Woody Allen.[8]Unfortunately, by the time the climax at the casino was to be filmed, Peter Sellers and Orson Welles hated each other. So the filming of the scene where both of them face each other across a gaming table actually took place on different days with a double standing in for the other actor. A disgusted Peter Sellers left the movie before the completion of his filming. (Other accounts claim Sellers, in a fit of anger, "karate-chopped" director Joe McGrath -- a man he insisted on working with in the film -- and was fired.)[10]With Sellers now gone, the producers were forced to add different plots with David Niven, Andress, and Woody Allen (who wrote his own part) to fill out the full time of the film. A framing device of a beginning and ending with David Niven was invented to salvage the footage.[1] The new plot follows a ruse by the original James Bond to fight SMERSH with six other agents, all designated as "James Bond" -- namely, Baccarat master Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers), millionaire spy Vesper Lynd (Ursula Andress), Bond's secretary Miss Moneypenny (Barbara Bouchet), Bond's daughter with Mata Hari, Mata Bond (Joanna Pettet), and British agents "Coop" (Terence Cooper) and "The Detainer" (Daliah Lavi) -- to confuse SMERSH. The film's slogan then became: "Casino Royale is too much... for one James Bond!" Tremble is abruptly killed in the film after being rescued by Vesper in a troop of bagpipe players, with by a later-filmed shot of her then shooting him with a converted bagpipe gun, followed by a shot of her surrounded by dead bodies, including -- presumably -- Tremble.[1] In the original theatrical release, a cardboard cutout of Sellers was used for the final scene, in which all the Bonds are angels in Heaven. In later versions, this cardboard image was replaced with an outtake of Sellers in highland dress (Sellers is actually blowing out some candles, but the image is used so that he appears to blow Jimmy Bond out of the clouds, down to Hell). |

|

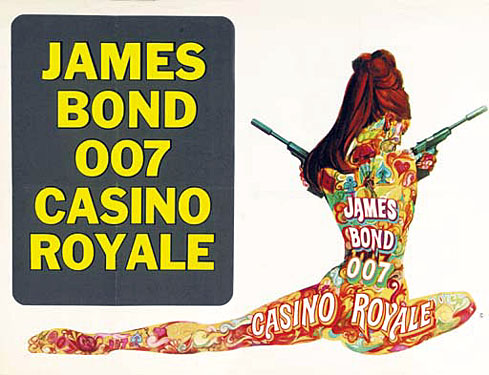

Despite the lukewarm nature of the contemporary reviews, the pull of the James Bond name was sufficient to make it the thirteenth highest grossing film in North America in 1967 with a gross of $22.7 million and a worldwide total of $41.7 million[16] ($291 million in 2012 dollars[17]). Orson Welles attributed the success of the film to a marketing strategy that featured a naked tattooed lady on the film's posters and print ads.[6] In 2011, director Joe McGrath told the Daily Mail: "Peter negotiated an astonishing three per cent of the film, which I recently discovered has now grossed 120 million pounds. Amazingly, it’s still earning money." (Source: 'Money still rolling in from Peter Sellers's James Bond spoof Casino Royale' by Ephraim Hardcastle; 21 October 2011, Daily Mail)

Jean Paul Belmondo and George Raft received major billing, even though both actors are only on screen for about 10 seconds each. Both appear during the climactic brawl at the end, Raft flipping his trademark coin and promptly getting shot, while Belmondo appears wearing a fake moustache as the French Foreign Legion officer who requires an English phrase book to say "ooch!" when he punches people.[6] At the Intercon science fiction convention held in Slough in 1978, Dave Prowse commented on his part in this film, apparently his big-screen debut. He claimed that he was originally asked to play "Super Pooh", a giant Winnie The Pooh in a superhero costume who attacks Tremble during the Torture Of The Mind sequence. This idea, as with many others in the film's script, was rapidly dropped, and Prowse was re-cast as a Frankenstein-type Monster for the closing scenes. The final sequence was principally directed by former actor and stuntman Richard Talmadge.[1]

This film also takes credit for the greatest number of actors in a Bond movie either to have appeared or to go on to appear in the rest of the 'official' series. Besides Ursula Andress (shown below in a deleted sequence in which Vesper was killed in the casino), Vladek Sheybal appeared as 'Kronsteen' in From Russia With Love, Angela Scoular appeared as 'Ruby Bartlett' in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Burt Kwouk featured as a SPECTRE operative in You Only Live Twice, Jeanne Roland appeared in the same film as a Masseuse. Finally Caroline Munro, who was an extra, took a much larger role as 'Naomi' in The Spy Who Loved Me. Also appearing was the scuba suit from Goldfinger with the duck attached to the cap (it was worn by Moneypenny, but the sequence was also dropped).

|

- Woody Allen (letter to Richard O'Brien)

Woody Allen was one of the only people to profit from this film. For what was supposed to be a six-week part, he stayed in London for six months on a good salary and expense account at the film's expense, wrote a play (Don't Drink the Water), re-wrote future films (Take the Money and Run and Bananas), wrote short stories for The New Yorker (later to appear in the books Getting Even, Without Feathers, and Side Effects), and won enough at poker to purchase an Emile Nolde watercolor and a drawing by Oscar Kokoschka.

Allen claimed his part was chopped to expand Sellers' -- another feud that didn't help matters. Eventually, despite all of his good fortune, producers delayed Allen's final day of shooting so many times, that out of frustration he left the set, went directly to Heathrow Airport and flew back to New York City without changing out of his costume.

Despite scathing reviews, the film was a big hit, and actually outgrossed the EON Bond entry that year, You Only Live Twice.

The "chaotic" nature of the production was featured heavily in contemporary reviews. Roger Ebert said "This is possibly the most indulgent film ever made,"[13] and Variety said "it lacked discipline and cohesion."[14] Some later reviewers have been more impressed by the film. Andrea LeVasseur, in the AllMovie review, called it "the original ultimate spy spoof", and opined that the "nearly impossible to follow" plot made it "a satire to the highest degree". Further describing it as a "hideous, zany disaster" LeVasseur concluded that it was "a psychedelic, absurd masterpiece".[2] Robert von Dassanowsky has written an article on the artistic merits of the film and says "like Casablanca, Casino Royale is a film of momentary vision, collaboration, adaption, pastiche, and accident. It is the anti-auteur work of all time, a film shaped by the very zeitgeist it took on."[3] Writing in 1986, Danny Peary noted, "It's hard to believe that in 1967 we actually waited in anticipation for this so-called James Bond spoof. It was a disappointment then; it's a curio today, but just as hard to get through." Peary described the film as being "disjointed and stylistically erratic" and "a testament to wastefulness in the bigger-is-better cinema," before adding, "It would have been a good idea to cut the picture drastically, perhaps down to the scenes featuring Peter Sellers and Woody Allen. In fact, I recommend you see it on television when it's in a two-hour (including commercials) slot. Then you won't expect it to make any sense."[15] Conversely, Romano Tozzi complimented the acting and humour, although he also mentioned that the film has several dull stretches.[21]

.png)

Music

The single most successful element of the film was the soundtrack, with original music by Burt Bacharach, while Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass performed some of the songs with Mike Redway singing the lyrics to the title song as the end credits rolled. (A version of the song was also sung by Peter Sellers.) The title theme was Alpert's second number one on the Easy Listening chart where it spent two weeks at the top in June 1967 and peaked at number twenty-seven on the Billboard Hot 100.[22]

"The Look of Love", performed by Dusty Springfield and heard during the Peter Sellers segment. Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Song, it has become a standard for its era. It was heard again in the first Austin Powers film, which was to a great degree inspired by Casino Royale. The 4th chapter of the film features the song "The Look of Love" performed by Dusty Springfield. It is played in the scene of Vesper Lynd recruiting Evelyn Tremble, seen through a man-size aquarium in a seductive walk.[23] "The Look of Love" was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song. The song was a Top 10 radio hit at the KGB and KHJ radio stations. A year later a version by Segio Mendes and Brasil '66 reached #4 of Billboard Hot 100. Springfield's version was heard again in the first Austin Powers film, which was to a degree inspired by Casino Royale.

The German version of the film, however, features a German adaptation of "The Look of Love" sung by Mireille Mathieu. To make room for her credit in the film titles, the credit for Jean-Paul Belmondo was removed in the German language version.

In another link to the EON series, composer John Barry's song "Born Free" was also used in the film. At the time, Barry was the main composer for the EON Bond series.

The original album cover art was done by Robert McGinnis, based on the film poster and the original stereo vinyl release of the soundtrack (Colgems #COSO-5005) is still highly sought after by audiophiles. It has been regarded by some music critics as the finest-sounding LP of all time.[24][25]

One cut conspicuously absent from the earlier film soundtrack issues is the vocal version of the title song, heard over the film's end credits and sung by Mike Redway.[26] The album merely replays the instrumental opening theme in the last track.

Rights

Columbia Pictures distributed this version of Casino Royale. In 1997, following the Columbia/MGM/Kevin McClory lawsuit on ownership of the Bond film series, the rights to the film reverted to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (whose sister company United Artists co-owns the Bond film franchise) as a condition of the settlement.[11]

Years later, as a result of the Sony/Comcast acquisition of MGM, Columbia would once again become responsible for the co-distribution of this 1967 version as well as the entire Eon Bond series, including the 2006 adaptation of Casino Royale. However, MGM Home Entertainment changed its distributor to 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment in May 2006, and MGM Television started to self-distribute again. Sony still controls the 2006 adaptation and theatrical rights to this version.

Alongside six other MGM-owned films, the studio posted Casino Royale on YouTube.[12]

The British Premiere benefited "Hurt Minds Can Be Healed," a mental health charity.

Films, main

The Sixties

Studio Portraits || European Enigmas || Italian Jobs || Kovert Komedy || Hong Kong Humint || 00-XXX || Boob Tube

Main Page

| Films, main | The Sixties |