"THE

WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH" -- IAN FLEMING

|

"It is possible to treat Bond's adventures as partly a joke,

grin at his car and his concealed weapons, boo at his enemies, whistle when the

girl appears, groan heavily when he gets captured, cheer when he works his thousand-to-one

chance of escape? That sort of thing happens when the three so far extant Bond

films are shown. It's a send-up, see? - partly, anyway. Sean Connery gives a gambling-joint

doorman five pounds and they laugh, we laugh; we don't laugh when Bond slips the

chef de partie a hundre- mille plaque after a win in Casino Royale. Nor does the

author. Mr. Fleming probably laughed about what he wrote, but he doesn't laugh

in his writing. I approve. I enjoy the films and the laughs in the films, but

I like the books better."

- Kingsley Amis, "The James Bond Dossier," 1965

"Lovely, wonderful man. He was James Bond."

- Albert Broccoli,

"The Incredible World of 007," 1992

"He had great energy and curiosity

and he was a marvelous man to talk to and have a drink with because of the many

wide interests he had..."

- Sean Connery, "Playboy" Interview, November,

1965

"Fleming was an incredible snob."

- Roger Moore to Dick Cavett,

1980

"I knew Ian, funnily enough, but I never particularly liked him. We

became, eventually, enormously good friends, but I thought he was a pompous son

of a bitch, immensely arrogant, and when we met just after I'd been signed to

do the picture at some big press show put on by United Artists, he said, 'So they've

decided on you to fuck up my work.'"

- Director Terrence Young

Most thrillers are written

by tired hacks, who sit in front of a typewriter 14 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Most are overweight, overtired, and have no life experience beyond their word

processors. They work out their stories as if they were doing their homework in

the fourth grade. Their love is in the craftsmanship, their plots are more like

math problems than high adventure. Most thrillers are written

by tired hacks, who sit in front of a typewriter 14 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Most are overweight, overtired, and have no life experience beyond their word

processors. They work out their stories as if they were doing their homework in

the fourth grade. Their love is in the craftsmanship, their plots are more like

math problems than high adventure.

James Bond's creator was never like that.

Like Bond, he abhorred 'the soft life." Ian Fleming really was a spy. He lived

a fast, adventurous, and (at least until he was married) wild life. And even after

he married, much of his year was spent on treasure hunts or exploring for his

news service. Listen to an interview with him here

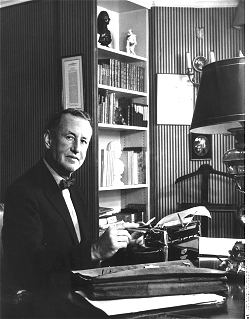

Fleming reserved just two months per year for Bond. Away

from England, between spear-fishing, parties, shark-feeding, and golf, he crafted

each thriller in a primitive house overlooking the seas of Jamaica.

The rest of the year, Fleming worked as an adventure journalist, and his crisp

but detailed descriptive style added greatly to the 007 book series. At first

the books fed off his own war experiences, but later he seemed to use Bond to

live out his fantasies -- of still being a handsome bachelor spy. Finally, as

heart disease overtook him, he used 007 to confront his fear of death. (He is buried in Swindon at St. James's church, just yards from his former home, pictured at right.)

In many ways, Fleming is just as fascinating as his creation.

"A

WHISPER OF LOVE, A WHISPER OF HATE."

THE

BOOKS

"The Russians believed Fleming's description of a

spy agency to such an extent that the arrival of a Bond alternative, in the form

of John le Carre's spies, created a fierce controversy among their intelligence

analysts."

- Peter St. John, professor of political Science at the University

of Manitoba, Winnipeg

"There is a surprising degree of reality in

the novels. Fleming was high enough up in intelligence systems during the war

to know how they worked and his writing reflected a keen sense of prevailing Western

political sentiments."

- Peter St. John, professor of political Science

at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

"He had achieved the rare

combination of exciting plot with dull heroes and overwhelming boredom."

-

Kim Philby (the Third Man), British double agent who secretly worked for the KGB

(what do you expect from a Commie traitor, anyway?)

Intellectuals

will hate to hear this, but Ian Fleming is possibly the most influential writer

of the 20th century. Hemingway and Fitzgerald changed the themes and narratives

of modern writing, but Fleming went beyond influencing just other novelists: his

writing changed film, television, and our entire culture - not always for the

better, necessarily, but profoundly. Because he worked in a particular genre,

his effect was more subversive: not through the critics and scholars that define

what is to be read in "important" literature, but through the popular culture.

There is not a TV show or movie that isn't somehow influenced by Fleming or by

what he created.

It should be noted that the Bond books were actually

MORE successful than the films up until Fleming's death. The twelve Bond books

published during Fleming's life were translated into 11 languages and grossed

60 million dollars - an astronomical sum in 1964 (and not too shabby today).

STYLE

"His

central device, the wildly improbable story set against a meticulously detailed

and somehow believable background, is vastly entertaining; and his redoubtable,

implacable, indestructible protagonist, though some think him a srangely flat

character, may well be not so much the child of this century as of the next."

- New York Times

Fleming wrote entertainingly,

and in a sense he is the main character of the books. James Bond is basically

a soulless, unhappy civil servant, constantly bored with his job. But the writing

makes the story fun -- if 007 lacks personality, the writing definitely does not.

This is why Bond needs to be funny in the films -- the writing for a film has

to be invisible, so now Bond has to entertain us through all the plot twists,

brutality, and gore.

"My

plots are fantastic, while being often based upon truth. They go wildly beyond

the probable but not, I think, beyond the possible. Even so, they would stick

in the gullet of the reader and make him throw the book angrily aside - for a

reader particularly hates feeling he is being hoaxed - but for two technical devices:

first, the aforesaid speed of the narrative, which hustles the reader quickly

beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly, the constant use of familiar

household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still

got their feet on the ground. A Ronson lighter, a 4.5-litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers

super-charger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London, the

21 Club in New York, the exact names of flora and fauna, even Bond's Sea Island

cotton shirts with short sleeves. All these details are points de rep?re to comfort

and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure."

--Ian

Fleming, "How To Write a Thriller"

In

the books, Fleming goes into great detail to describe every meal, gun, girl, facial

characteristic and even shampoos to make us believe what we are reading is real.

This is important, because if we don't believe that stuff, we'll never believe

in pet giant squids, undiscovered rocket bases, stolen atomic bombs, or germ-warfare

dispensing allergy clinics in the Alps. "Of course it's all real," we say, "because

if it isn't why is Bond carrying a battered oxidised black Ronson lighter with

his gunmetal cigarette case containing specially made Macedonian blend cigarettes

with three gold rings around the butt from Morlands of Grovenor Street?"

Fleming's easy use of detail and brand-names to define his characters helped blaze

a new style in popular literature where the real world and the fictional world

collided. That style helped create the product placement we see in every film

and TV show we see today (although it's used more for financial than aesthetic

reasons now ).

In fact the product placement that so many critics complain

about in the Bond films is actually one of the stronger links they have to the

books.

Fleming meets the real James Bond.

Fleming meets the real James Bond.

|

MAIN CHARACTER

"The

real everyday world of spies, of killing people, of treachery is nasty. Fleming

didn't really like it and I think he made Bond not really like it either. It is

surprising the number of books in which Bond is totally unenthusiastic about the

world in which he lives."

- Timothy Dalton: "The Making of Licence To Kill"

Unlike the film character, the Bond of the books is actually

an "everyman," Slight of build and quite fallible in his decisions, he's no smarter

or funnier than the reader - it's his adventures that are stylish. The reader

is thus allowed to experience the adventure through Bond, not just admiring the

wit and toughness of the main character as in a Chandler book. We become Bond

as we read.

"I wanted to show a hero without

any characteristics, who was simply the blunt instrument in the hands of the government,"

said Fleming. "I quite deliberately made him anonymous. This was to enable the

reader to identify with him. People have only to put their own clothes on Bond

and build him into whatever sort of person they admire. If you read my books you'll

find that I don't actually describe him at all." See how he came up with his character's name here.

Bond enjoys high-stakes

gambling, the best wines and champagnes, automobiles, and cigarettes, but is apart

from these trappings of class. He's just a civil sevant with great job benefits.

Outside of a maid, he lives his everyday life just like most of us -- only he's

better at it.

|

TEXTURE

"Ian

Fleming introduced the element of the adventure story into the spy story. He took

all those big 1930's Bentleys on the highways and put them into his work. Nobody

had done anything like that before."

- Len Deighton, author of "The Ipcress

File" and the Bond screenplay "Warhead." With

the outlandish plots Fleming dreamed up for Bond, he had to make it seem as believable

as possible to keep the reader involved (something that the movie makers should

remember). Every gun, food, wine, building, and death throe was studiously researched

to heighten the realism.

Fleming loved to

research, and he was always storing information away for his Bond novels. O.F.

Snelling recalled hearing Fleming on a radio show with Raymond Chandler. Fleming

proudly announced that he had learned that the first thing a man does after awakening

from being knocked unconcious is to vomit. Sure enough, in the next Bond novel,

007 gave an authentic heave after reviving himself.

On another occasion,

he questioned a former Navy friend and polar explorer who had written a survival

manual for escaped P.O.W.'s. A delighted Fleming questioned the man about a hypothetical

situation in which a Russian stood between him and starvation: what would be the

best part of a man to eat? The explorer evaded the question as long as he could,

but Fleming persisted - would it be the palm of the hand? Finally he got his answer:

A cut of the rib. Fortunately in the later Bond books, James stuck to scrambled

eggs.

"My

books tremble on the brink of corn."

- Ian Fleming |

HUMOR

The Bond books are full of tongue-in-cheek humor.

While Bond himself is not a humorous person, often the action around him is.

The books can be self-referential without cutting into the drama and believability:

In Bond's obituary in You Only Live Twice, M even comments on the books

(and he's not very impressed). In On Her Majesty's Secret Service Bond

sees actress Ursula Andress -- who was the current

Bond movie girl in Dr. No.

(The humor

continued into the John Gardner era, when in the

novel Scorpius, Bond watches a movie on an airplane featuring his favorite

actor - Sean Connery.

These jokes do not

cut into Bond's believability (as a lot of in-jokes in the films

do). Bond is still a real person, living through it all, not a joke himself. Somebody

should've explained that to Roger Moore...

SEX

"In the sixties, we thought the James Bond books were

extremely naughty! We wouldn't take a second look now; the sex in those books

is extremely tame compared to what we're used to in the modern novel."

-

John Gardner, Bondage #11

While the James Bond

of Fleming's writing expressed his fears and doubts about his missions and actions,

Bond never expressed doubts concerning the attraction he felt for certain women.

James Bond never paused before a kiss, nervously concerned with rejection. In

fact, Bond's only real rejection in the novels (by Gala Brand in Moonraker) comes

as a brutal shock. This inner confidence made both Bond and Fleming heroes of

the more sexually open world of the 50s and 60s.

By 1960 Ian Fleming, James Bond, and Playboy magazine became a nearly synonymous

cultural force, truly united with Playboy's publication of The Hilderbrand Rarity.

The union of styles and tastes continued beyond Fleming's death into the mid-sixties.

Fleming's heroines, while certainly not paragons of feminism, are universally

strong, and often tragic figures. Rarely damsels in distress, the "Bond women"

(or more commonly, "Bond girls") tend to have their own agendas, solid strengths,

and an ability to stand on their own.

VILLAINS

"It's no accident that Mr. Big is always a millionaire.

You never get Bond going down dark alleys or looking for villains. He's always

in the lap of luxury. He's always going to exotic places, which takes the audience

into marvelous realms."

- Guy Hamilton, director of "Goldfinger," "Diamonds

are Forever," and "Live And Let Die"

Fleming's

villains provide the author with great opportunity to explore larger themes. Through

the grand schemes of Mr. Big, Sir Hugo Drax, Goldfinger, Dr. No, and Ernst Stavro

Blofeld, Fleming wages a literary battles with the deadly sins. Sloth, vengeance,

greed, and snobbery are but some of the dragons Bond must battle in human form.

STRUCTURE

Fleming had a basic formula for his Bond books, which he rarely strayed

from. They usually began with a teaser - an action scene that actually occurs

later in the narrative. After this event, the novel would flash back and lead

up to the first scene later in the story. Fleming used this devise to hook the

audience, yet still allow him the slow narrative build-up he needed to create

a suspenseful thriller.

Action shows on TV now use Fleming's narrative

formula religiously. Every cop and detective show tries to hook the viewer by

opening with an action-packed scene from the middle of the story ("Tonight, on

Magnum P.I."), then flashes back in the to reveal how we reached this particular

point.

The Bond films use this formula, but not within the narrative:

they try to hook the viewer with a wild stunt, then begin the story after the

titles (this is one of the many reasons some Bond films feel so long and disjointed).

Fleming also built his chapters to lead the reader along into the next chapter.

Each chapter has its own cliffhanger, defying the reader to put the book down.

Today on TV, scenes are pointed to lead the viewers past commercial breaks, much

like Fleming tried to sweep readers along, chapter to chapter.

|

"The craft of writing sophisticated thrillers is almost

dead. In this age of higher education, writers seemed to be ashamed of inventing

heroes who are white, villains who are black, and heroines who are a delicate

shade of pink.

"I am not an angry young, or

even middle-aged man. I am not 'involved.' My books are not 'engaged.' I have

no message for suffering humanity and, though I was bullied at school and lost

my virginity like so many of us used to do in the old days, I have never been

tempted to foist these and other harrowing personal experiences on the public.

My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something.

They are not designed to find favor with the Comintern. They are written for warm-blooded

heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes or beds..."

- Ian Fleming, "How

To Write a Thriller," 1962

|

interview/profile of Ian Fleming

that appeared in The New Yorker on April 21 1962. Enjoy!

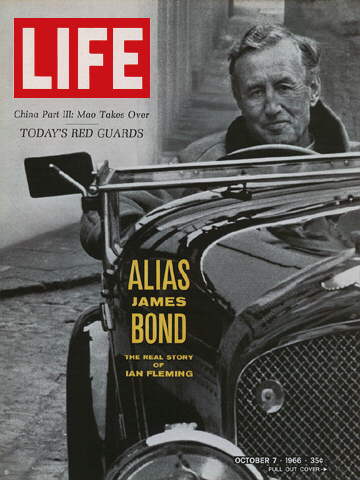

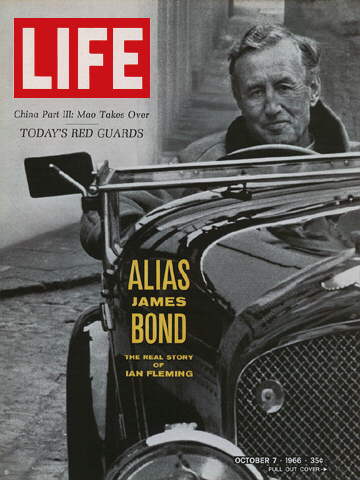

Bond's Creator Ian Fleming, whose nine Secret Service thrillers ("Casino Royale,"

"Doctor No," "For Your Eyes Only," "From Russia with Love,"

"Live and Let Die," "Moonraker," "Goldfinger," "Diamonds

Are Forever," and "Thunderball") have had phenomenal sales in

this country and abroad (more than eleven hundred thousand hardcover

copies and three and a half million paperbacks), was here for a weekend

recently en route from his Jamaica hideaway to his London home, and we

caught him on a Sunday morning at his hotel, the Pierre, where he

amiably stood us a lunch. He ordered a prefatory medium-dry Martini of

American vermouth and Beefeater gin, with lemon peel, and so did we.

"I'm here to see my publishers and assorted crooks," he said.

"Not other assorted crooks, mind you. By 'crooks' I don't mean

crooks at all; I mean former Secret Service men. There are one or two

of them here, you know."

"Who?" we asked.

"Oh, men like the boss of James Bond, the operative who's the chief

character in all my books," said our host. "When I wrote the first

one in 1953, I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man

to whom things happened; I wanted him to be a blunt instrument. One of

the bibles of my youth was 'Birds of the West Indies,' by James

Bond, a well-known ornithologist, and when I was casting about for a

name for my protagonist I thought, My God, that's the dullest name

I've ever heard, so I appropriated it. Now the dullest name in the

world has become an exciting one. Mrs. Bond once wrote me a letter

thanking me for using it."

Mr. Fleming, a sunburned, tall, curly-haired, blue-eyed man of

fifty-three in a dark blue suit, blue shirt, and blue-dotted bow tie,

ordered another Martini, and so did we. "I've spent the morning in

Central Park," he said. "I went to there to see if I'd get

murdered, but I didn't. The only person who accosted me was a man who

asked me how to get out. I love the park; it was so wonderful to see

the brown turning to green. I went to the Wollman skating rink and saw

all those enchanting girls skating around, and then I thought, This is

the place to meet a spy. What a wonderful place to meet a spy! A spy

with a child. A child is the most wonderful cover for a spy, like a dog

for a tart. Do tarts here have dogs? I was interested to see that in

the bird reservation in the Park there was not a single bird. There are

no people there--it's fenced in, you know, with a sign--but no

birds either. Birds can't read."

Mr. Fleming lit a Senior Service cigarette and, in answer to some

questions from us, said he was a Scot, that he had been brought up in a

hunting-and-fishing world where you shot or caught your own lunch, and

that he was a graduate of Eton and Sandhurst. "I shot against West

Point," he said. When I got my commission, they were mechanizing the

Army, and a lot of us decided we didn't want to be garage hands

running those bloody tanks. My poor mamma, in despair, suggested I try

for the diplomatic. My father was killed in the '14-'18 war. Well,

I went to the Universities of Geneva and Munich and learned extremely

good French and German, but I got fed up with the exams, so in 1929 I

joined Reuters as a foreign correspondent and had a hell of a time.

Wonderful! I went to Moscow for Reuters. My God, it was fun! It was

like a tremendous ball game."

He ordered a dozen cherrystones and a Miller High Life, and we followed

suit. "I like the name 'High Life,'" he said. "That's why I

order it. And American vermouth is the best in the world."

He added that he had been with Reuters for four years, and we asked

what happened next.

"I decided I ought to make some money, and went into the banking and

stock-brokerage business--first with Cull & Company and then with

Rowe & Pittman," he said. "Six years altogether, until the war came

along. Those financial forms are tremendous clubs, and great fun, but I

never could figure out what a sixty-fourth of a point was. We used to

spend our whole time throwing telephones at each other. I'm afraid we

ragged far too much."

We inquired about the war, from which, according to the British Who's

Who, Mr. Fleming emerged a naval commander, and he said, "I was

personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence, so I went

everywhere."

We asked what he'd done after the war.

"I joined the editorial board of the London Times," he said. "I

still write articles for it, and I'm a stockholder. And in 1952, when

I was in Jamaica, Cyril Connolly asked me to write an article about

Jamaica for his magazine, Horizon. It was rather a euphoric piece,

about Jamaica as an island for you and me to go to. "

We promised to go, and he said, "How about some domestic Camembert?

It's better here than the French."

During this and coffee, he reverted to the non-ornithological James

Bond. "I think the reason for his success is that people are lacking

in heroes in real life today," he said. "Heroes are always getting

knocked--Philip and Mountbatten are examples of this--and I think

people absolutely long for heroes. The thing that's wrong with the

new anticolonialism is that no one has yet found a Negro hero.

They're scratching around with Tshombe, but...Well, I don't regard

James Bond precisely as a hero, but at least he does get on and do his

duty, in an extremely corny way, and in the end, after giant despair,

he wins the girl or the jackpot or whatever it may be. My books have no

social significance, except a deleterious one; they're considered to

have too much violence and too much sex. But all history has that. I

finished the last one, my tenth James Bond story, in Jamaica the other

day; it's long and tremedously dull. It's called 'The Spy Who Loved

Me,' and it's written, supposedly, by the girl. I think it's an

absolute miracle that an elderly person like me can go on turning out

these books with such zest. It's really a terrible indictment of my

own character--they're so adolescent. But they're fun. I think

people like them because they're fun. A couple of years ago, when I

was in Washington, and driving to lunch with a friend of mine, Margaret

Leiter, she spotted a young couple coming out of church, and she

stopped our cab. 'You must meet them,' she said. 'They're great

fans of yours.' And she introduced me to Jack and Jackie Kennedy.

'Not the Ian Fleming!' they said. What could be more gratifying

than that? They asked me to dinner that night, with Joe Alsop and some

other characters. I think the President likes my books because he

enjoys the combination of physical violence, effort, and winning in the

end-like his PT--boat experiences. I think James Bond may be good for

him after the dry pack of the day."

Mr. Fleming is married to the former wife of Lord Rothermere and has a

nine-year-old son, Caspar, who is away at boarding school. "He

doesn't read me, but he sells my autographs for seven shillings a

time," his father said.

Main Page

|

Most thrillers are written

by tired hacks, who sit in front of a typewriter 14 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Most are overweight, overtired, and have no life experience beyond their word

processors. They work out their stories as if they were doing their homework in

the fourth grade. Their love is in the craftsmanship, their plots are more like

math problems than high adventure.

Most thrillers are written

by tired hacks, who sit in front of a typewriter 14 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Most are overweight, overtired, and have no life experience beyond their word

processors. They work out their stories as if they were doing their homework in

the fourth grade. Their love is in the craftsmanship, their plots are more like

math problems than high adventure.