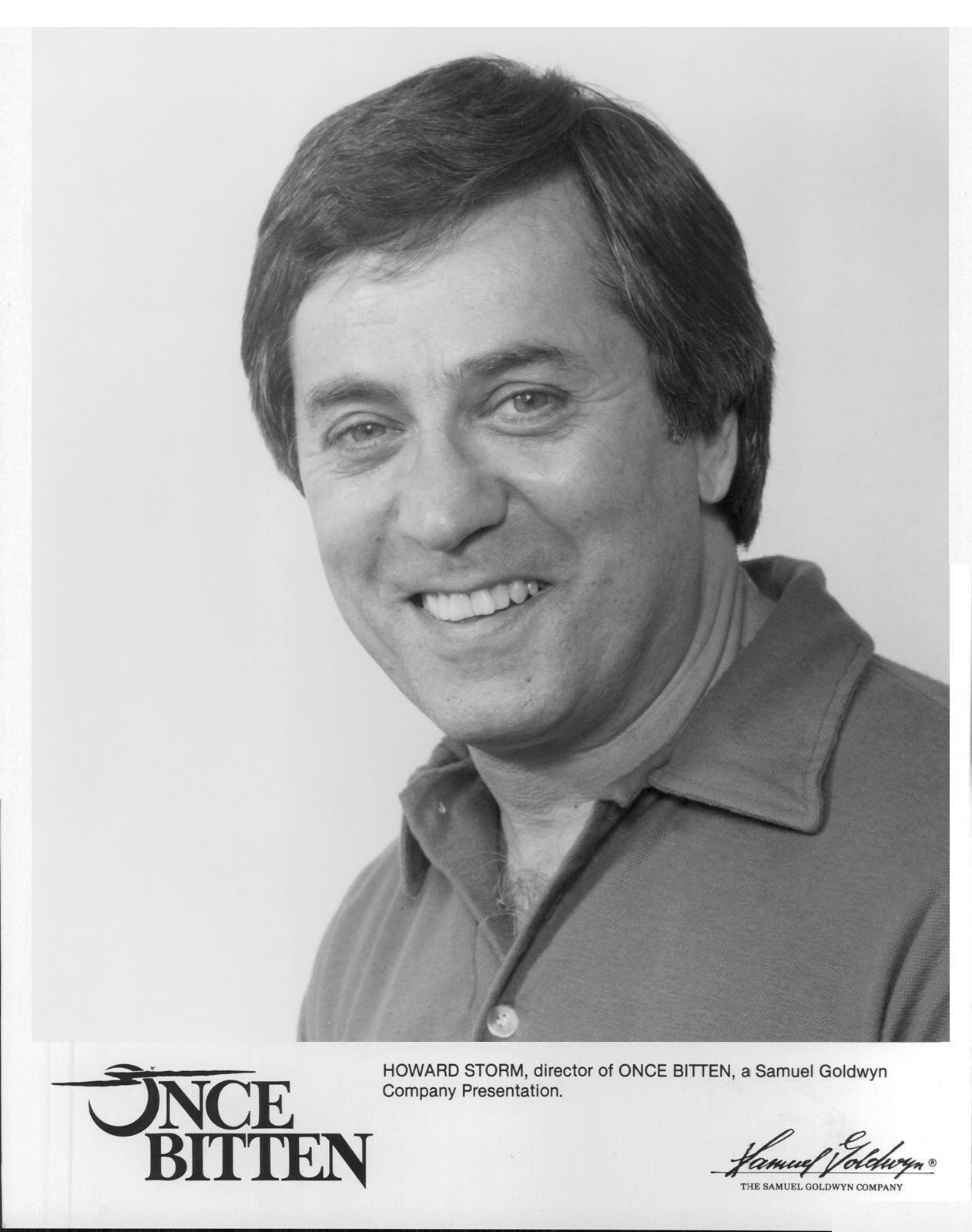

HOWARD STORM, ANNOTATED

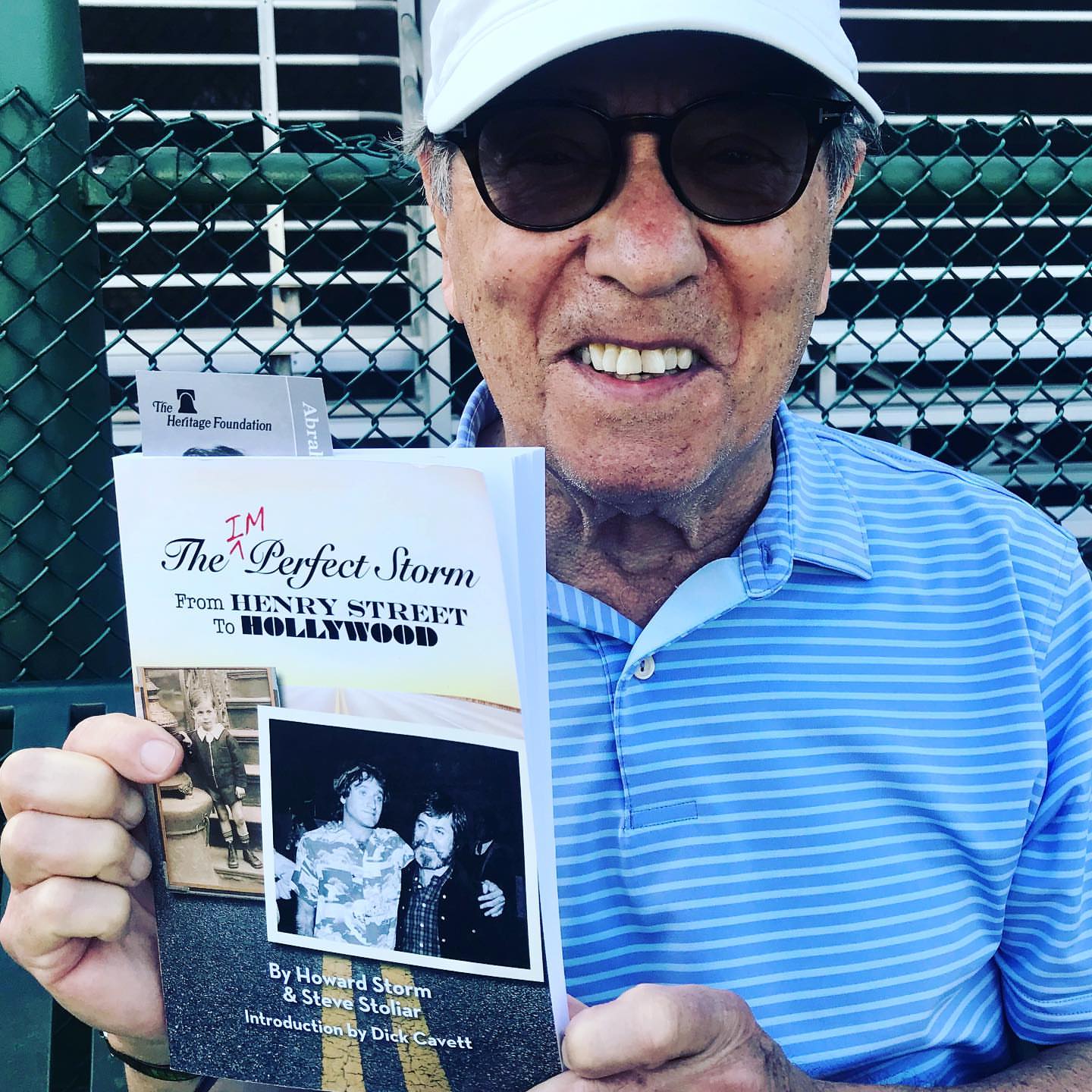

"THE IMPERFECT STORM: From Henry Street To Hollywood (Publication Date: October 2, 2019), by Howard Storm & Steve Stoliar, is, according to the advertising, "the improbable—and vastly entertaining—story of Howard Storm (nee Howard Sobel), who grew up on the mean streets of New York's Lower East Side during the Great Depression and went on to become a successful standup comic, actor, improv teacher, and television director." "THE IMPERFECT STORM: From Henry Street To Hollywood (Publication Date: October 2, 2019), by Howard Storm & Steve Stoliar, is, according to the advertising, "the improbable—and vastly entertaining—story of Howard Storm (nee Howard Sobel), who grew up on the mean streets of New York's Lower East Side during the Great Depression and went on to become a successful standup comic, actor, improv teacher, and television director."

The following is transcribed from the autobiography of Howard Storm, pertaining to his work on the film Once Bitten. Our film is a minor blip on his pretty spectacular career... but after 25 years of putting up with my account of things on this page, he gets to blast me back! Come for the lamentable Once Bitten anecdotes, stay for the stories of Robin Williams' brilliance. Let me say upfront that this book was written by an 86-year-old man, recounting his entire career to a writer, who then records each hazy event as he interprets it, so a 35-year-old story can change completely, through nobody's fault. I have no desire to spoil the pride of an old man looking back over a great TV career at his one theatrical film. So I will say that my responses are just the events as I remember them, and Howard is welcome to his own opinion. The text from the book is in a white-colored font, and my notes on each passage are in yellow. (Notice how the yellow patches grow larger as I get more angry.)

"Imperfect Storm," Chapter 28 (Pages 165-169)

Page 165: "After Mork & Mindy runs its course, one of the show's writers, Ed Scharlach, teams up with Sam Goldwyn Jr.'s wife, Peggy, to write scripts. One day, Sam asks Ed, 'Do you know of a television director that can work fast and knows comedy?' Ed says, 'Yeah, Howard Storm.' Another writer, Wally Dalton, has a meeting with Sam about another project and he's asked the same question. Wally answers, 'Yeah, Howard Storm.' I get a call from Mr. Goldwyn, who tells me, 'It's really interesting. I spoke to two different people and both of them gave me your name.'"

MY NOTE: Originally, the Samuel Goldwyn Company had looked at established film guys, and even some music video directors. Many of the candidates felt the mix of horror and comedy would be hard to pull off. I had always heard that Howard was first suggested by producer Dimitri Villard's receptionist, Shelley, who was Richard Pryor's ex-wife and knew Howard personally—and it was actually Dimitri who had convinced Samuel Goldwyn Jr. to look at him. I guess Howard's story could be true, too. My only question would be, why was Goldwyn looking for a TV director, specifically, when doing a film? I don't remember all of the directors they interviewed, but we were already several drafts into the script before they finally hired Howard. My account of the entire experience can be read here.

Page 165: "Sam gives me a script called Once Bitten, I read it, then meet with him to discuss it. We agree on the script's strengths and weaknesses, then make a deal to do the movie. It's a terrific experience."

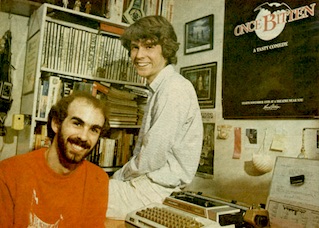

| Two fresh-faced, foul-mouthed kids—trying to fake it 'til they make it. We pose here in Dave's chicken coop house for the cover of a local magazine upon the film's release. We were sure that the corresponding "after" photo was going to look incredible!! |

|

MY NOTE: I think they felt the main weakness of the script was... us—Dave Hines and me. We were both barely 20 years old—raw, with no experience. We had no mentors to guide us; no agent, no manager—all of our friends were still in college (I was a junior at Long Beach State, until Goldwyn made me quit). Frankly, we were in way over our heads. Goldwyn was used to dealing with experienced pros, but we had never done rewrites before, so our first pass was a complete page-1 do-over, giving them a totally different script in tone and approach than the script they had bought (we made vampirism an allegory for herpes). After the initial freak-out by the production team, the comedy was restored with our next draft... but I think by that point, Goldwyn had decided to bring on a comedy vet to keep us in-line for future drafts. Unfortunately, Howard was just not that guy—he had no interest in teaching two doofus rookies the art of comedy (which is understandable, since he was busy enough trying to make his first feature) and was used to a veteran TV writers room, where they delivered changes without much guidance or fuss. We never met with him, never worked in the room with him, never discussed our progress, and flat-out never talked. We just saw him with everybody else in production meetings after we turned in each draft.¹ Goldwyn was loyal to writers (if he wasn't, I'm sure our jobs would have gone to more experienced writers like Scharlach or Dalton right after that first rewrite), but we just didn't click with Howard. It's telling that Howard writes he met with Goldwyn to talk about the strengths and weaknesses of our script, but he never says that he liked our script; I think he just wanted to direct a feature film when his time on Mork and Mindy ended, and this was the script he was offered.

Page 165: "The film isn't intended as a Jim Carrey vehicle. We see a load of different actors, but when Jim comes in, he really connects. We read him two or three times before we sign him. Jim is very easy to work with and he's very happy to have the lead in a movie, because this is his first feature film." Page 165: "The film isn't intended as a Jim Carrey vehicle. We see a load of different actors, but when Jim comes in, he really connects. We read him two or three times before we sign him. Jim is very easy to work with and he's very happy to have the lead in a movie, because this is his first feature film."

MY NOTE: Read "ANECDOTE #1 here. Goldwyn and the producers actually went to see Carrey perform standup at a comedy club after he auditioned (not sure if Howard attended), but according to one of them, Carrey bombed. He did so poorly that he finally crawled into the grand piano onstage and closed the lid behind him. After the host finally came back out and introduced the next act, Carrey quietly climbed out and crept offstage. (I have heard that Carrey actually did this on more than one occasion, but would he have carried a grand piano around with him for one joke?) Anyway, climbing out of that wooden compartment must have seemed enough like emerging from a coffin that they gave him the part.

Page 165: "The writers and producers want to go with Cassandra Petersen (sic)—TV's Elvira, Mistress of the Dark—for the female vampire lead. I tell them, 'That's a cartoon. That's ridiculous. I don't want to do that. Let's get a real actress to play it,' so we bring in Lauren Hutton, who is just wonderful in the part."

MY NOTE: Not that it matters to this story, but since we're mentioned, we didn't push for Cassandra Peterson. In fact, we offered no suggestions for the role of the Countess at all in our casting notes to the studio. In the months before the Samuel Goldwyn Company became involved with the project, producers Dimitri Villard and Robby Wald were in negotiations with Peterson (who is actually a pretty good actress) to play a scarier, vampiric version of her "Elvira" character—which was never a vampire in concept; in fact, she was a witch in her own movie, filmed a couple of years later. She wasn't going to be "Elvira" in the film, she was going to play "The Countess." Dimitri and Robby definitely didn't want her to just be her TV character (which was only on local TV then, and probably would have meant attaching other producers); They knew Peterson was funny, but they wanted her to stretch and be scary. After that fell through, Dimitri and Robby had approached Patti Smyth of the group Scandal to play the Countess in a musical version of the film, to be scored by the new wave/synth-pop band Sparks and directed by Michael Peters, who choreographed Michael Jackson's videos (including Thriller, which had a big influence on the first draft of our script). However, by the time the Samuel Goldwyn Company purchased the script, the musical idea had been dropped and it was submitted with no actors attached. MY NOTE: Not that it matters to this story, but since we're mentioned, we didn't push for Cassandra Peterson. In fact, we offered no suggestions for the role of the Countess at all in our casting notes to the studio. In the months before the Samuel Goldwyn Company became involved with the project, producers Dimitri Villard and Robby Wald were in negotiations with Peterson (who is actually a pretty good actress) to play a scarier, vampiric version of her "Elvira" character—which was never a vampire in concept; in fact, she was a witch in her own movie, filmed a couple of years later. She wasn't going to be "Elvira" in the film, she was going to play "The Countess." Dimitri and Robby definitely didn't want her to just be her TV character (which was only on local TV then, and probably would have meant attaching other producers); They knew Peterson was funny, but they wanted her to stretch and be scary. After that fell through, Dimitri and Robby had approached Patti Smyth of the group Scandal to play the Countess in a musical version of the film, to be scored by the new wave/synth-pop band Sparks and directed by Michael Peters, who choreographed Michael Jackson's videos (including Thriller, which had a big influence on the first draft of our script). However, by the time the Samuel Goldwyn Company purchased the script, the musical idea had been dropped and it was submitted with no actors attached.

As I remember, Howard actually wanted to cast Morgan Fairchild in the role of the Countess, because she had worked with him on Mork & Mindy (here is how I took the news in my sketchbook), but apparently she said no or was unavailable. IMDb lists Kathleen Turner as another candidate, but at the time she was making much larger films like The Jewel of the Nile and Prizzi's Honor, so I sincerely doubt it. Francis Ford Coppola, who directed her next film, called Peggy Sue Got Married, actually requested to see rough footage of Carrey in Once Bitten and then hired him for a supporting role in that film.

|

Page 165: "As originally written, Lauren's assistant is a bald, heavyset mute. He doesn't say a word in the entire film. I say, 'To make it more interesting, why don't we get a black guy who's very elegant and erudite and proper?' The first one we go after is Roscoe Lee Browne. I did a bit with him in a TV movie called The Big Rip-Off ten years earlier and I think he's terrific. Roscoe isn't available, so we go with Cleavon Little, who's so great in Blazing Saddles. He's a pleasure to work with, a great actor, and he knows where 'funny' is. Changing Lauren's assistant from a heavyset mute white guy to Cleavon Little brings a whole new tone to the film."

MY NOTE: There was never a "heavyset mute white guy," unless one was added after we left the project. Originally, the Countess had a number of zombie-like former victims who were her attendants, dressed in plaid disco suits and punker clothes (inspired by Michael Peters and Thriller, with its walking-dead dancers). Howard's idea was to add a "Renfield" character for the Countess, in the form of a bumbling valet named "Otto" who did a lot of pratfalls—which we did, but everybody hated it (especially us). It was clumsy physical comedy with no point or context, i.e., it had no reason to be in the film because it had no effect on the plot, so it wasn't ever going to be funny—it just made all the scenes longer. We removed the pratfalls in the next draft and made "Otto" a more typical Renfield-style valet (describing him as "a tall, immaculately groomed black gentleman"), but I don't remember adding anything new for Otto, either, so he was probably pretty bland at that point, and I could see Howard wanting to make him more interesting.

We met with Russ Thacher a few days later over lunch and quit the project, saying we had nothing left to add after two years of rewrites (for which we were earning about $500 a month, when you break it down, and as a result Dave was living in a converted chicken coop with his new wife and I had moved back in with my parents, inspiring my sketchbook drawing, at right). Besides, we hadn't been adding anything about vampires for months: In our last pass, while removing the clumsy valet, we had added bits for the characters of "Russ" and "Jamie," trying to pick up women in a pretty funny laundromat scene, and then a pointless one at a women's prison, which was cut. We never said goodbye to Howard... who immeditely brought in another writer named Jonathan Roberts and did a polish, including their infamous talking parrot (footnote #5). We met with Russ Thacher a few days later over lunch and quit the project, saying we had nothing left to add after two years of rewrites (for which we were earning about $500 a month, when you break it down, and as a result Dave was living in a converted chicken coop with his new wife and I had moved back in with my parents, inspiring my sketchbook drawing, at right). Besides, we hadn't been adding anything about vampires for months: In our last pass, while removing the clumsy valet, we had added bits for the characters of "Russ" and "Jamie," trying to pick up women in a pretty funny laundromat scene, and then a pointless one at a women's prison, which was cut. We never said goodbye to Howard... who immeditely brought in another writer named Jonathan Roberts and did a polish, including their infamous talking parrot (footnote #5).

Howard's note about the valet being "elegant and erudite and proper" eventually evolved over his draft with Jonathan Roberts into the character of "Sebastian" in the finished film, which became a lazy gay caricature. Roscoe Lee Brown spent his entire career avoiding stereotyped roles, so I'm guessing as soon as he read that the character stepped out of the closet wearing the Countess's scarf, saying elegant and erudite things like "I came out of the closet centuries ago" and talking about attacking Little Leaguers , he became extremely "unavailable." (Sebastian's punchline about venturing into the suburbs for Little Leaguers was cut from the film after the first couple of test audiences gasped; as a result, the line now ends abruptly with the set-up line, "Chicken McNuggets.") However, the main problem with the character is he's competely unnecessary—which is why he changed completely in every draft without altering the story at all—in Dracula, Renfield had a story and moved the plot (he was a lawyer who traveled to Transylvania to assist the title character in moving out of the country, then became his victim/slave, like our disco guys, and we watch his descent into madness), but Sebastian is just a butler; even in Howard's own draft, "Sebastian" has no backstory, no impact on the other characters, or any of the scenes, and is so inconsequential that the story would play exactly the same if you removed him; In fact, after the first couple of scenes, he is just standing next to the Countess every time you see him, with no purpose. I always advocated for cutting him completely and giving the Countess more to do, again.

I mean, here's the problem: Who the f@$& is Sebastian???? Is he another vampire? If so, why is he a butler? Is he Renfield? Is he a "familiar" like Guillermo in What We Do in the Shadows? Was he a past victim like the other minions in the basement? Howard and Roberts never told us who he was in the movie and obviously didn't care. He was just a gay joke with no backstory, and had no effect on the film's plot at all; by the end of the film he was just standing around frowning with nothing to do. It was lazy, horrible writing and we got the blame.

Page 166: "In the script, Jim Carrey's two friends work in a hamburger joint. I say, 'Jim should have a job, too. If his two friends work, it looks a little strange if he's not working. But we need to find a job where he can be out and about, because he has to run into Lauren.' We come up with an ice cream truck that he drives after school and that works out nicely." Page 166: "In the script, Jim Carrey's two friends work in a hamburger joint. I say, 'Jim should have a job, too. If his two friends work, it looks a little strange if he's not working. But we need to find a job where he can be out and about, because he has to run into Lauren.' We come up with an ice cream truck that he drives after school and that works out nicely."

MY NOTE: Plenty of kids don't work at a job while they're in high school... but the ice cream truck is fine, I guess (the only problem is it's an involved, budgeted effect that could have been better spent on, say, some decent VAMPIRE MAKE-UP). Carrey's two friends work in a burger joint, but that doesn't prevent them from being "out and about" with Carrey's character in Hollywood, so it's not exactly crucial that they drive an ice cream truck into Hollywood instead of a family station wagon, like in our script... but whatever. Note for completists: The ice cream truck in this film was actually blown to bits a year later in the Andy Griffith Show TV movie reunion, entitled Return to Mayberry.

Page 166: "Sam Goldwyn Jr. screens Terminator for me and suggests Polish cinematographer, Adam Greenberg, as my Director of Photography. I tell him, 'His stuff looks great.' We set up a lunch meeting with Adam and the producer and throughout the entire meeting, all I get from Adam is 'Yes' and 'No.' I can't get any conversation going with him. Later, I tell Sam, "I have to be able to communicate with my cinematographer, but I got nothing from him except yeses and nos. I've got to have a guy that relates to me.' Sam says, 'Would you be willing to fly to Vegas where Adam's shooting a movie and discuss that with him and maybe give him a second shot?' (Greenberg was shooting a teen sex comedy called Jocks, that was so bad it was never released, followed by Private Resort, a teen sex comedy so bad that stars Johnny Depp and Rob Morrow swore a pact to track down and destroy every copy.) I tell him, 'Sure.' I go to Vegas and Adam takes me to a Chinese restaurant, then proceeds to tell me his amazing life story about being a little boy in Poland when the Nazis invaded, escaping with his family to Israel, and eventually becoming a cameraman. After that, we get along great and I'm delighted to bring him onboard as our cinematographer." Page 166: "Sam Goldwyn Jr. screens Terminator for me and suggests Polish cinematographer, Adam Greenberg, as my Director of Photography. I tell him, 'His stuff looks great.' We set up a lunch meeting with Adam and the producer and throughout the entire meeting, all I get from Adam is 'Yes' and 'No.' I can't get any conversation going with him. Later, I tell Sam, "I have to be able to communicate with my cinematographer, but I got nothing from him except yeses and nos. I've got to have a guy that relates to me.' Sam says, 'Would you be willing to fly to Vegas where Adam's shooting a movie and discuss that with him and maybe give him a second shot?' (Greenberg was shooting a teen sex comedy called Jocks, that was so bad it was never released, followed by Private Resort, a teen sex comedy so bad that stars Johnny Depp and Rob Morrow swore a pact to track down and destroy every copy.) I tell him, 'Sure.' I go to Vegas and Adam takes me to a Chinese restaurant, then proceeds to tell me his amazing life story about being a little boy in Poland when the Nazis invaded, escaping with his family to Israel, and eventually becoming a cameraman. After that, we get along great and I'm delighted to bring him onboard as our cinematographer."

MY NOTE: We basically had the same experience with Howard. Goldwyn set us up at a hotel in Beverly Hills (you can read the story here).

Page 166: "As a first-time feature film director, I'm a little shaky, so Adam helps me a lot. I set up one shot and he tells me, 'Y'know, Howard, I was thinking: Why don't we put the camera here and then move the camera? Then we wind up where you wanted to start your shot.' I say, 'In other words, you're saying, 'Move the camera. Don't be static.' I'm so used to working on weekly television shows, I don't always think of creative ways to use the camera."

MY NOTE: This is why I question the story of Sam Goldwyn Jr. only looking for TV sitcom directors. Now, I need to admit something here, because I'm about to get very critical: While I'm very forgiving of the mistakes made by newbies Dave and me in these stories, I'm less charitable with Howard, even though it was his first movie, too. That's very unfair. All of us—Howard included—were learning how to build a story and pace a 90-minute film, which is a lot different than creating a 20-minute network sitcom with an A-story, a B-story, and three commercial breaks (that form of sitcom is actually gone now, as Howard laments in his chapter for Everybody Loves Raymond, one of the last of the type).² During the 1980s, film and television were two very different mediums. Sitcoms usually had three video cameras set up for every scene ("Mork and Mindy" had four, with an extra camera to follow Robin Williams if he improvised). The camera crew basically recorded everything as if it was a play, in long-shot, mid-range and close-up, and then the scene was assembled in the editing room. It was a factory environment, and there wasn't any thought put into camera movement, style, or making one episode appear different from another. In fact, the goal was to look just like every other episode (Howard actually complains that they changed Mork & Mindy too much between seasons, and caused it to fail).

It goes beyond just the look, however: Sitcom writing was different than film, because there was no character development: Mork from Ork in season three was supposed to be the same as Mork from Ork in season one, and all of Howard's disputes with Robin Williams in this book were over Robin complaining that his character would change over time, and he was tired of saying, "Shazbot" and "Nanu-nanu," and being completely naïve to the ways of Earthlings after fifty episodes. Howard's job as a TV director was to keep everything from drifting or changing. That way you don't have to go to the writer working on episode #10 and say, "Change everything! We just decided that Mindy is an alien in hiding, too, while re-writing episode #5!" Plus, the audience can watch the entire run of the show out of order in syndication and never be confused. A film isn't like that—characters each have an arc with a beginning, middle and end, and their conflicts need resolution. For instance, in our written ending, Russ and Jamie become confident vampires rather than remain high school outcasts, but the finished film never reveals that—the last time we see them, they're flirting with vampire girls, using the same pick-up lines and mannerisms that they had in the Phone-A-Date club an hour earlier in the film, with no pay-off. As for the main characters, we were supposed see the downside of being a vampire through Mark's dreams, which show him as a lonely undead teenager, living alone in a creepy graveyard, harming the people he loves (Robin, a peasant girl), with angry villagers pursuing him with torches and stakes. As Mark physically starts to change in his daily life, his dreams become more real until they actually overtake reality at the school dance (this was mixed in with the stuff about him winning 'best costume' as a vampire, and disappearing in the mirror). Howard threw all of our dreamscape stuff out and made them all unrelated set pieces (for instance, in one dream the Countess runs her foot up Mark's thigh in a restaurant). Because of this, it's hard to understand why Mark doesn't want to be a vampire—he'd give up his sexually frustrated life with Robin and live forever with a hot blonde giving him foot-jobs in nice restaurants, without aging. Even a scene we had showing that Mark would not be together with the Countess, but instead would live in a coffin with the other undead in the crowded lair below (his coffin had Star Wars sheets) was cut out of the film. It goes beyond just the look, however: Sitcom writing was different than film, because there was no character development: Mork from Ork in season three was supposed to be the same as Mork from Ork in season one, and all of Howard's disputes with Robin Williams in this book were over Robin complaining that his character would change over time, and he was tired of saying, "Shazbot" and "Nanu-nanu," and being completely naïve to the ways of Earthlings after fifty episodes. Howard's job as a TV director was to keep everything from drifting or changing. That way you don't have to go to the writer working on episode #10 and say, "Change everything! We just decided that Mindy is an alien in hiding, too, while re-writing episode #5!" Plus, the audience can watch the entire run of the show out of order in syndication and never be confused. A film isn't like that—characters each have an arc with a beginning, middle and end, and their conflicts need resolution. For instance, in our written ending, Russ and Jamie become confident vampires rather than remain high school outcasts, but the finished film never reveals that—the last time we see them, they're flirting with vampire girls, using the same pick-up lines and mannerisms that they had in the Phone-A-Date club an hour earlier in the film, with no pay-off. As for the main characters, we were supposed see the downside of being a vampire through Mark's dreams, which show him as a lonely undead teenager, living alone in a creepy graveyard, harming the people he loves (Robin, a peasant girl), with angry villagers pursuing him with torches and stakes. As Mark physically starts to change in his daily life, his dreams become more real until they actually overtake reality at the school dance (this was mixed in with the stuff about him winning 'best costume' as a vampire, and disappearing in the mirror). Howard threw all of our dreamscape stuff out and made them all unrelated set pieces (for instance, in one dream the Countess runs her foot up Mark's thigh in a restaurant). Because of this, it's hard to understand why Mark doesn't want to be a vampire—he'd give up his sexually frustrated life with Robin and live forever with a hot blonde giving him foot-jobs in nice restaurants, without aging. Even a scene we had showing that Mark would not be together with the Countess, but instead would live in a coffin with the other undead in the crowded lair below (his coffin had Star Wars sheets) was cut out of the film.

Page 166: "We're shooting the scene where Lauren seduces Jim. I decide to shoot it in sequence. The last shot of the night is Lauren telling Jim, "I'm going to go upstairs and slip into something more comfortable." In the morning, we're going to shoot her coming down the steps in a negligee, looking very sexy. I add a moment where she bites the buttons off his shirt, top to bottom, one at a time, and spits them out, then her head disappears out of frame. It's a lot of sexy fun." Page 166: "We're shooting the scene where Lauren seduces Jim. I decide to shoot it in sequence. The last shot of the night is Lauren telling Jim, "I'm going to go upstairs and slip into something more comfortable." In the morning, we're going to shoot her coming down the steps in a negligee, looking very sexy. I add a moment where she bites the buttons off his shirt, top to bottom, one at a time, and spits them out, then her head disappears out of frame. It's a lot of sexy fun."

MY NOTE: First off, we added the button biting in our last draft (although Howard may have suggested it), but is it really "sexy fun?" I'm beginning to understand why Howard's been married three times. Secondly, she was really biting the buttons off of actual shirts? That couldn't have been easy with fake fangs.

Page 166-7: "The next morning, I come to the set and I have all my shots set up. I talk things over with Adam and we're ready to go. Suddenly, Lauren appears at the top of the stairs wearing black lipstick and black nail polish and her hair is in a completely different style than it was the previous night. I ask Lauren, 'What is this? You go up to change into a negligee and you take all your makeup off and you put fresh makeup on, take all your nail polish off and put fresh nail polish on and you change your hair-do? That would take two and a half hours.' She says, 'I want to look sexy for him.' I tell her, 'That's ridiculous. No woman in the world that wants to seduce a guy would go upstairs and take two and a half hours to get ready.' I turn to the makeup guy and ask, 'Who allowed this?' He says, 'She told me you said it was okay.' I call the heads of all the departments together and I tell them, 'Nobody accepts anything unless you come to me and clear it first.' I lose two and a half hours. Lauren has to go back, take off all the makeup, and get back to looking like she did when she went upstairs. All through the shoot, Lauren is telling me, 'I should have spiked hair.' I tell her, your character wouldn't have spiked hair.' She says, 'Oh, but it would look so cool!' I tell her, 'Lauren, when you direct your own movie, you can have spiked hair, but I'm directing this one." She calls me a wuss, but she has a great personality and I really love working with her. In another scene, Lauren is in the dressing room of a department store and Ted, the lighting director, is up on a ladder, setting the light. Lauren calls out, 'Ted!' He looks down just as she flashes her tits at him. He almost falls off the ladder. She does goofy things like that constantly, which is a lot of fun."

MY NOTE: The first time the director saw the lead actress that morning was when they were shooting her first take in front of the camera??? Sounds like I wasn't the only one Howard didn't communicate with. Anyway, Hutton did try to run the set sometimes—at least she did when Dave and I visited the shoot at the Whisky A Go-Go in West Hollywood.³ The camera crew had set up an overhead shot of Hutton sitting in a low-cut outfit at the bar, and every member of the film crew had found a reason to be up with the camera, in order to get a look down her top. Producer Russ Thacher, who was introducing us around, was then informed that Hutton had made the crew change the tracks that were laid on the floor for a moving camera shot—completely altering how the scene would be filmed—and that Howard was upset, so apparently he and Hutton butted heads more than once. Russ then left to deal with that—he didn't introduce us to Hutton, because he was afraid she would start demanding script changes. (Which is understandable, I guess. When she signed on, it was a vampire movie with teens in it. By the time it was shot, it was a teen movie with a vampire in it.) So we stayed silent, didn't introduce ourselves as the original writers, and quietly looked down her top with the rest of the crew. MY NOTE: The first time the director saw the lead actress that morning was when they were shooting her first take in front of the camera??? Sounds like I wasn't the only one Howard didn't communicate with. Anyway, Hutton did try to run the set sometimes—at least she did when Dave and I visited the shoot at the Whisky A Go-Go in West Hollywood.³ The camera crew had set up an overhead shot of Hutton sitting in a low-cut outfit at the bar, and every member of the film crew had found a reason to be up with the camera, in order to get a look down her top. Producer Russ Thacher, who was introducing us around, was then informed that Hutton had made the crew change the tracks that were laid on the floor for a moving camera shot—completely altering how the scene would be filmed—and that Howard was upset, so apparently he and Hutton butted heads more than once. Russ then left to deal with that—he didn't introduce us to Hutton, because he was afraid she would start demanding script changes. (Which is understandable, I guess. When she signed on, it was a vampire movie with teens in it. By the time it was shot, it was a teen movie with a vampire in it.) So we stayed silent, didn't introduce ourselves as the original writers, and quietly looked down her top with the rest of the crew.

Page 167: "I find a spot to put my kids, Casey and Anthony, in the film. They ride their bikes up to Jim Carrey to buy ice cream. Jim turns around and he's got the vampire fangs and they both take off running. (Wrong. There weren't even FANGS! Again, DECENT VAMPIRE MAKEUP would have been nice. It's all Carrey pantomiming, with no pointy teeth, no monster character design, nothing—yet people jumped; that's how good Carrey was.) I have the camera set up so that when Jim turns around and looks in the mirror, he sees the steeple of a church behind him and he runs into the church to talk to a priest. I tell Adam, 'When he comes into the church, I'd like to put a camera up in the balcony and shoot down on him with a wide lens. As he walks down the aisle, we tilt up and reveal the entire church.' Getting that shot requires a lot of lighting and a lot of hiding of the lights." Page 167: "I find a spot to put my kids, Casey and Anthony, in the film. They ride their bikes up to Jim Carrey to buy ice cream. Jim turns around and he's got the vampire fangs and they both take off running. (Wrong. There weren't even FANGS! Again, DECENT VAMPIRE MAKEUP would have been nice. It's all Carrey pantomiming, with no pointy teeth, no monster character design, nothing—yet people jumped; that's how good Carrey was.) I have the camera set up so that when Jim turns around and looks in the mirror, he sees the steeple of a church behind him and he runs into the church to talk to a priest. I tell Adam, 'When he comes into the church, I'd like to put a camera up in the balcony and shoot down on him with a wide lens. As he walks down the aisle, we tilt up and reveal the entire church.' Getting that shot requires a lot of lighting and a lot of hiding of the lights."

PAGE 168: "Adam says, 'You know what we can do? I can lay some track and we can follow him and see the archways and then we'll get to the altar.' I tell him, 'I want it to be Chaplinesque. I want it to look like he's in this giant church and he's a small figure who's all alone, so I want the wide lens and I want it up high so that he looks smaller than he really is. Then we tilt up and reveal the whole church.' Adam is trying to avoid the problems and the time it will take to light a scene like that. The producer (probably Russ Thacher) comes in and says, 'Adam's right. You can just lay some track.' I tell him, 'I know, but I want that shot. I know it's going to take a long time to set up the lights, but I'm willing to take some other shots out to make up for it, because this is important to me.' We do it my way and at the dailies, Sam turns to me and says, "Howard, that is a great shot."

MY NOTE: Greenberg knew they were needlessly filming two establishing shots in a row; the first was the shot of Carrey seeing the church's steeple in a side-view mirror on that friggin' ice cream truck (that wasn't a process shot and also took a lot of work and time to set up), so the location of the scene was already established and you didn't need another shot to pan up and reveal the church a second time.

Plus, this shows that Howard had no feel for the material, and didn't understand the story. The church scene wasn't about Mark being seen as a tiny figure inside a giant religious institution; at that moment in the story, Mark is scared that he's becoming a vampire—eternally damned as an enemy of the church—so a chapel would feel scary and unnatural to him with its flaming candles, holy water, bright light streaming through stained-glass windows, and crosses looming everywhere—not just... large. As for the shots that Howard said he sacrificed... I'm just going to assume they were more of our jokes.

Anyway (calming down)... Goldwyn watched the dailies every night, and one of the producers told us that Sam was panicking, and so he was constantly calling the set, demanding re-shoots, without revising the budgets. The completed vampire dream sequences all had to be re-shot because Goldwyn thought they looked too dark and old-fashioned. A graveyard set was scrapped and replaced with a hastily-devised white bedroom with walls made of what appear to be clear shower curtains; bright light shines through the window (vampire, Sam... no sunlight); The campy 'old-time-movie' element of the dream sequence was therefore gone, and it just looked like a modern scene with bad effects. Anyway (calming down)... Goldwyn watched the dailies every night, and one of the producers told us that Sam was panicking, and so he was constantly calling the set, demanding re-shoots, without revising the budgets. The completed vampire dream sequences all had to be re-shot because Goldwyn thought they looked too dark and old-fashioned. A graveyard set was scrapped and replaced with a hastily-devised white bedroom with walls made of what appear to be clear shower curtains; bright light shines through the window (vampire, Sam... no sunlight); The campy 'old-time-movie' element of the dream sequence was therefore gone, and it just looked like a modern scene with bad effects.

An intentionally cheezy-looking bat was visible through the brightly-lit window, and was now an obvious anachronism, flapping its plastic wings robotically. A person sitting in front of me at a preview screening whispered, "Couldn't they get a more realistic bat?" As much as I disagreed with Howard, I always felt bad for him that Goldwyn undermined him that way. In the end, though, this was Sam's movie: In the original theatrical posters, his name is over title ("Samuel Goldwyn Jr.'s Once Bitten")—not Howard's or Hutton's or Carrey's (and definitely not ours)—and he called the shots: His movie, his vampire, his shower curtains. Still, photos of the actors rehearsing on the old-fashioned sets were chosen to sell the film on posters and video boxes—even though those scenes weren't used in the film, itself—because they actually looked like they were out of a vampire movie. An intentionally cheezy-looking bat was visible through the brightly-lit window, and was now an obvious anachronism, flapping its plastic wings robotically. A person sitting in front of me at a preview screening whispered, "Couldn't they get a more realistic bat?" As much as I disagreed with Howard, I always felt bad for him that Goldwyn undermined him that way. In the end, though, this was Sam's movie: In the original theatrical posters, his name is over title ("Samuel Goldwyn Jr.'s Once Bitten")—not Howard's or Hutton's or Carrey's (and definitely not ours)—and he called the shots: His movie, his vampire, his shower curtains. Still, photos of the actors rehearsing on the old-fashioned sets were chosen to sell the film on posters and video boxes—even though those scenes weren't used in the film, itself—because they actually looked like they were out of a vampire movie.

Page 168: "In another scene, Cleavon disappears into the kitchen. You can't see him, but you hear glasses tinkling and then he appears with a tray and he goes up a staircase. He makes a turn and continues going up the steps. I want the camera to follow him up, which means putting a high hat on the camera, which is a metal attachment that gives you more space to shoot. Poor Adam has to stand on his toes in order to look into the frame, but we get the shot and it works out fine. Then I notice that at the top of the set, there's a ledge that isn't painted, because it wasn't going to be in the shot as originally planned. Every time I watch the movie, I notice that, but I don't think anybody else does."

MY NOTE: Have you noticed a consistent theme here through all of Howard's changes? It's that none of his work has had anything to do with vampires—or even setting the tone for a vampire movie. They're all just about gay butlers and wide-angle church shots, and suburban kids looking out of place in upper-class Beverly Hills (like every other teen sex comedy being made at the time). Now, I get that when Hutton is biting the buttons off of Carrey's shirt, you don't want to play it like she's a vampire—you want to film a typical '80s sex comedy blowjob scene with our twist at the end that she's going to bite him down there. But the others: a two-minute scene of Cleavon Little wandering around a house dusting and straightening picture frames, mixing drinks offscreen while we wait, then carrying a tray up two flights of stairs (it became the entire title sequence); Two separate establishing shots of a church that took all day to shoot, including a misguided "Chaplinesque" angle that took extra hours to set up and forced him to sacifice other shots; An ice cream truck that doesn't factor into the story in any way; And changing a sleazy, dimly-lit bar in Hollywood full of goths and punks where a vampire could hide into a lame "Phone-a-Date" club in Beverly Hills with valets, a uniformed doormen, and formally-dressed patrons communicating via lip-shaped land lines; This is a director trying to be showy in a way that doesn't help the film, the theme, or the story. Howard never tried to film our screenplay in a way that served the subject matter (vampires), or the satire (Hollywood as Transylvania); he took the story out of Hollywood and instead dropped a fantasy figure into the suburbs—essentially the set-up for his last job, Mork & Mindy—making it a 90-minute situation comedy, playing to what he perceived to be his strengths (instead of the screenplay's). Howard was given a script in which a modern boy (Michael J. Fox, who became Jim Carrey during the course of casting) was dropped into an updated vampire movie. Instead, Howard reversed that and dropped the vampire into Orange County, muting Carrey's comic style and making him the straight man, and transferred all the fish-out-of-water comedy to Lauren Hutton, who wasn't a trained comic actor like Williams or Carrey. Suddenly the comic and horror possibilities are a lot more limited—the Countess just became a rich Beverly Hills MILF slumming it with an inexperienced middle-class teenager, playing like every other teen comedy of the time, beat-for-beat, with Hutton in the generic Sybil Danning/Sylvia Kristel 'rich-experienced-MILF' role. (Did I just compare Mork from Ork to a MILF? Well, I guess he did give birth to Jonathan Winters in one episode.)

"I'm as stubborn about the material as I am about getting the shots I want. In the original version of the scene where Jim goes into the church, there's a homeless wino, played by Gary Goodrow from The Committee. He's sitting in a confessional and he turns to the priest through the little window, asking, 'Do you have any toilet paper? I'm all out.' I tell the writers, 'There's no way I'm going to shoot this joke.' I tell Sam, 'I'm not shooting this joke. The guy is shitting in a confessional in a church! It's insulting to Catholics and it's insulting to me—and I'm not a Catholic.'"

MY NOTE: Howard COMPLETELY mis-remembers here. Even his description of the scene is wrong: Gary Goodrow does not ask a priest for toilet paper. The actual scene has a desperate Carrey enter the church and run into Goodrow's "wino" character, who is sleeping in a pew; Carrey then enters the confessional. The wino watches him, then goes into the next door, beside Carrey's. Hearing somebody enter the other side of the booth, Carrey begins his confession and admits his sin of premarital sex, and reveals that because of his transgression he's becoming a vampire... but when he's done confessing and asks for guidance, the voice coming from the other side of the booth responds, "You got any toilet paper on that side? I'm all out over here." The Confessional Scene was filmed as written, and we saw it play that way in a rough cut at the Goldwyn screening room, sitting next to songwriters Billy Steinberg and Tom Kelly (who wrote Like a Virgin for Madonna—and they laughed HARD at this joke, by the way). But Samuel Goldwyn Jr. had it re-dubbed in post, because of a potential Catholic church backlash (the offending punchline was replaced with Howard's golden zinger, "You're in deep shit," which I guess they felt would be a favorite line of the Pope's). In fact, in the finshed film you can still hear the "wino" grunting and straining as he defecates in the next booth—so this supposed "I won't shoot it" tirade directed at us just never happened. (Howard barely talked to us at all, let alone about this scene in particular; and he didn't even change it after he brought in his own writer.) We found out that they changed the line—in post—when we attended a test screening in San Diego; After watching the entire audience sigh at the new punchline, my note to the producers was to remove the entire scene—because without the payoff it had no reason to exist... but without a church scene, there would be no "Chaplinesque" establishing shot, and then there would be no ice cream truck scene to set it up—meaning Howard's kids would have been cut out of the picture. Howard was never going to cut any of that. So instead of removing a dull, pointless scene, we're stuck with what we have left in the finished movie: "Shit." (Take that any way you want.) MY NOTE: Howard COMPLETELY mis-remembers here. Even his description of the scene is wrong: Gary Goodrow does not ask a priest for toilet paper. The actual scene has a desperate Carrey enter the church and run into Goodrow's "wino" character, who is sleeping in a pew; Carrey then enters the confessional. The wino watches him, then goes into the next door, beside Carrey's. Hearing somebody enter the other side of the booth, Carrey begins his confession and admits his sin of premarital sex, and reveals that because of his transgression he's becoming a vampire... but when he's done confessing and asks for guidance, the voice coming from the other side of the booth responds, "You got any toilet paper on that side? I'm all out over here." The Confessional Scene was filmed as written, and we saw it play that way in a rough cut at the Goldwyn screening room, sitting next to songwriters Billy Steinberg and Tom Kelly (who wrote Like a Virgin for Madonna—and they laughed HARD at this joke, by the way). But Samuel Goldwyn Jr. had it re-dubbed in post, because of a potential Catholic church backlash (the offending punchline was replaced with Howard's golden zinger, "You're in deep shit," which I guess they felt would be a favorite line of the Pope's). In fact, in the finshed film you can still hear the "wino" grunting and straining as he defecates in the next booth—so this supposed "I won't shoot it" tirade directed at us just never happened. (Howard barely talked to us at all, let alone about this scene in particular; and he didn't even change it after he brought in his own writer.) We found out that they changed the line—in post—when we attended a test screening in San Diego; After watching the entire audience sigh at the new punchline, my note to the producers was to remove the entire scene—because without the payoff it had no reason to exist... but without a church scene, there would be no "Chaplinesque" establishing shot, and then there would be no ice cream truck scene to set it up—meaning Howard's kids would have been cut out of the picture. Howard was never going to cut any of that. So instead of removing a dull, pointless scene, we're stuck with what we have left in the finished movie: "Shit." (Take that any way you want.)

See? Now I'm starting to get mad, again...

"We're having lunch and one of the producers, Robby Wald, comes into the restaurant. He gets on his knees and says, 'Please, please! You gotta do that joke! Without that joke the movie dies!' I tell him, 'Robby, what the hell are you talking about? It's not gonna die. It's one joke and not even a good joke. It's a tasteless joke and I'm not gonna shoot it. That's it.' I stand my ground, we change the gag to something else, and it's fine."

MY NOTE: In two paragraphs, we've gone from the inspiring phrase, "I'm stubborn about the material" to the much less inspiring phrase, "we change the gag to something else, and it's fine." This story is at least partially true. As related to me by two different sources, Robby Wald did actually do this, but he was asking for a vibrator gag from the opening scene of the script (at lover's lane) to be put back into the film, not the confessional scene—and thus Robby had gotten down on his knees in the restaurant and loudly begged, "Please re-insert the vibrator." (Which is a whole lot funnier than the actual gag.) Once again, Howard FILMED the confessional scene, so it wasn't that.⁴

We saw Howard two more times, first in a meeting to fix the ending, because the talking parrot they added had been cut and they needed a new end line (footnote #5, here), and then we saw him again at the cast and crew screening, when he walked over and said, "Fuck the critics." (The film had just gotten destroyed by two reviewers in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.) I didn't know what to say to him, because I agreed with the critics.

Page 169: "Years later, I'm having lunch with Sam Goldwyn Jr. and I tell him, 'Y'know, I think I made a mistake by sitting on Jim Carrey and holding him down, because I didn't want him too over-the-top.' Sam says, 'I think you're right. I should've seen that, too.' But while we're shooting, I don't want him mugging. I want him to be real, because he's a teenager who's being followed by a beautiful woman that he doesn't realize is a vampire. If I'd really let Jim run with it, it would've been a different movie. It would've been a cartoon." Page 169: "Years later, I'm having lunch with Sam Goldwyn Jr. and I tell him, 'Y'know, I think I made a mistake by sitting on Jim Carrey and holding him down, because I didn't want him too over-the-top.' Sam says, 'I think you're right. I should've seen that, too.' But while we're shooting, I don't want him mugging. I want him to be real, because he's a teenager who's being followed by a beautiful woman that he doesn't realize is a vampire. If I'd really let Jim run with it, it would've been a different movie. It would've been a cartoon."

MY NOTE: So four pages later in the autobiography, cartoons are GOOD, now? Interesting... The weird thing is that Howard's best-known work was Mork and Mindy... which was a comedy/fantasy featuring a stand-up comic who Howard allowed to improvise unceasingly—but for this comedy/fantasy, Howard decided that a stand-up comic improvising on the material was a bad thing. Hell, I'm one of the writers, so I'm all for sticking to the words—but just watching Carrey walk across the nightclub, you wanted to see what other great bits he could add... I mean, did you see that dance scene? Howard tried to get a writing credit for this film, so maybe he felt more ownership of the material—but we're talking about a comic genius, here, who was already outshining Howard and us. Despite declaring that Carrey "really connects" with the character, Howard continued "sitting on Jim Carrey and holding him down" (and after that last talking parrot rewrite, the film needed all the help it could get).

Page 169: "Nevertheless, I am very proud of Once Bitten and it remains a high point of my career." Page 169: "Nevertheless, I am very proud of Once Bitten and it remains a high point of my career."

MY NOTE: Sure, I wish it was funnier, but I'm proud to have been part of it, too—although I'm frustrated that it still makes me so angry, 35 years and dozens of scripts later. It survives because of Carrey's popularity (which he's not happy about), but as the film gets older, its flaws are forgiven and are just seen as being part of their time—such as the homophobia (Sebastian in the closet, the transvestite in the Phone-a-Date club calling Russ a "sissy," and the shower scene that Dave and I wrote—read footnote #3 here), the '80s fashions and music; the neon-lit music video montage of Beverly Hills; the slow pacing (my theory is that after years of TV directing, Howard unconsciously paced the scenes like they were going to have a sitcom laugh track), the bad makeup (Mark wins "Best Costume" at the high school dance for wearing sunglasses, an overcoat, and having his hair slicked back), a guy with an Indian accent who is supposed to be funny because... he has an Indian accent... (I could go on, but this will become longer than Howard's entire book!) Now they are kind of looked upon as kitschy historical markers, instead of the bad choices they were deemed to be during the original release. (Besides, our competition was stuff like Jocks and Private Resort—both also shot by Greenberg—and we're Oscar material compared to those teen comedies.)

For me, Howard added two great scenes to the film: The first was when the Countess is made up by her non-"heavyset mute white guy," Sebastian. She sits before an empty mirror frame on her makeup table, and Sebastian reaches through the frame to apply her makeup, because as a vampire she can't see a reflection to do it herself. We never wrote that, and I think it's terrific. (And it actually involves vampires!) The other addition was in the school locker room, when the two friends check the hero for bite marks. Howard added a "sort of comic ballet" (as described in his re-write with Roberts, but with no action noted, so this was all created in Howard's head, and works beautifully). Howard tracks Russ and Jamie as they follow the hero around the locker room and are constantly frustrated as they are about to inspect his crotch. Howard builds the suspense until they finally grab him and check him for sores in the shower, sending the other boys there into a panic (the joke in our script was that to straight middle-class kids, homosexuality was actually scarier than vampires). Anyway, Howard shot the sequence perfectly, the actors were great, and it made our payoff in the showers a hundred times funnier than it read on the page. Unlike the 'Clumsy Valet' stuff, THIS was physical comedy that added tension and advanced the plot—and it worked perfectly. For me, Howard added two great scenes to the film: The first was when the Countess is made up by her non-"heavyset mute white guy," Sebastian. She sits before an empty mirror frame on her makeup table, and Sebastian reaches through the frame to apply her makeup, because as a vampire she can't see a reflection to do it herself. We never wrote that, and I think it's terrific. (And it actually involves vampires!) The other addition was in the school locker room, when the two friends check the hero for bite marks. Howard added a "sort of comic ballet" (as described in his re-write with Roberts, but with no action noted, so this was all created in Howard's head, and works beautifully). Howard tracks Russ and Jamie as they follow the hero around the locker room and are constantly frustrated as they are about to inspect his crotch. Howard builds the suspense until they finally grab him and check him for sores in the shower, sending the other boys there into a panic (the joke in our script was that to straight middle-class kids, homosexuality was actually scarier than vampires). Anyway, Howard shot the sequence perfectly, the actors were great, and it made our payoff in the showers a hundred times funnier than it read on the page. Unlike the 'Clumsy Valet' stuff, THIS was physical comedy that added tension and advanced the plot—and it worked perfectly.

The film sort of set up unrealistic expectations for us, as well—our first film script was produced and so we just assumed everything else we'd write would get made—so we kind of abandoned Once Bitten when we were offered another script that became Meatballs III... which we also abandoned after the first story conference (at a bar), in order to write another spec script called For Better or Worse for Dimitri and Robby, with director Mark Lester. (Goldwyn Producer Russ Thacher even helped us with the story.) Fortunately, that script (finally) got us an agent—unfortunately, it was canceled just before casting started—we were already pushing for Carrey as the lead, since Back to the Future ($250 million gross) and Teen Wolf ($80 million gross) had opened and there was no way we could afford Michael J. Fox, anymore. After that movie fell apart, and our next script at Disney died when their "Sunday Movie" series was canceled, we slowly started to realize that every script we wrote wasn't going to get made, let alone debut in the #1 spot at the box office... and that maybe we should have stuck around and tried to make Howard's ideas work better instead of sulk and quit when he didn't use ours. What did happen is that every other director we worked with in our careers would meet us at any hour for coffee, drinks, lunch or dinner, hang around at each other's houses and offices, and talk, argue and spitball for hours in order to create a consistent vision, so that we could give that director the best version of the script he or she wanted to make. Never happened here.

After Once Bitten got all those horrible reviews and fizzled, our new agent sired us around town. We were presented as fresh newcomers in our early twenties, and he expressly told us not to mention Once Bitten in meetings! Unfortunately, I did mention it once, anyway. A producer on the show Brothers brought up the film during a meet-and-greet, so I defensively said the director had changed the script (in a snotty way, I'm sure) and it turned out that Howard was back working in TV and was directing the show. Howard will be happy to know that we were then summarily booted from the office.

FOOTNOTES:

¹—We had totally different visions for the film, but we never talked it through with him. The screenplay that Goldwyn bought dropped modern teens into a horror movie that played out in the setting of Hollywood, which was filled with bloodsuckers and out of virgins. Howard did the opposite with the script; it was what he helped do with Mork & Mindy: Take a fantasy character (a space alien in that show, and in our case, a vampire), move it out of its element, and drop it into the suburbs. Now, we deferred to Howard and definitely helped in that process, moving the scenes out of Hollywood over the course of two years' rewriting, but the Countess never left Hollywood in our original script—sort of a modernized Transylvania—and she lured Mark into her world, where she was in charge. Howard disagreed with that approach and wanted scenes of the Countess chasing Mark around Orange County (thus Sebastian's line about the Little Leaguers), which we argued was already the plot of Love at First Bite, right down to the big dance number, with the suburbs replacing New York City in a fish-out-of-water plot. It also made the story choppy and opened massive holes in the plot. In our original script, the Countess doesn't know where Mark lives and must lure him back to Hollywood through his dreams, and he can't resist that temptation; In the finished film, the Countess somehow knows where Mark lives and where he goes to school—and even where his girlfriend works (at a mall clothing store), and what time he'll be visiting her there. (How does she know Robin will make him try on sweaters in a changing booth—not to mention which booth he will go into? I DON'T KNOW.) She confronts Mark there, and decides that it would be the perfect moment to bite his inner thigh for a second time, while he's waiting for Robin to get him a new sweater... and then, after all that, she just LEAVES!!! (Why is the Countess leaving Mark in Orange County with the girlfriend he's trying to sleep with, when she still needs a third infusion of his virgin blood to survive??? Is it almost daylight? Is Robin wearing a cross? Are they serving too much garlic in the pizza at the food court next door? I DON'T KNOW.) Next, the Countess shows up at Mark's high school dance. (How does she know where the school is, what time the dance is, and why does she think this is a good time to bite him in front of a couple hundred witnesses? I DON'T KNOW!) The Countess and Robin then have a big showdown on the dance floor that turns into a dance-off—none of the faculty seem to care that an adult woman is attempting to stab one student and bite another—the Countess then... doesn't bite him and JUST LEAVES AGAIN!!! After she does that, the stalled plot that we wrote simply resumes on the dance floor, unchanged, with everybody ignoring what just happened and awarding Mark the "best costume" prize for slicking his hair back (i.e., being dressed as a vampire). You could literally pull the dance out of the story and nobody would know it was ever there. There's no cause and effect—it's just a set piece, dropped into the story for no particular reason. That kind of thing works much better in ten-minute sitcom intervals, between commercial breaks, than for 90 uninterrupted minutes onscreen in which you need the story to build, and for the audience to believe it, stay engaged, and root for or against the characters. The Countess just comes and goes for no particular reason, and it destroys the suspense, diffuses the feeling of being stalked or chased, negates all the urgency of the Halloween night ticking clock, and removes dramatic tension from the storyline (fancy theories for a dopey teen sex comedy, I know, but it matters). Finally, for the third and final bite, the Countess rides by limo to where Mark's friends work in Orange County (Sebastian is now reduced to being a driver with no lines) and she kidnaps... Robin (???), so that Mark (who watches all of this, a hundred feet away) will follow them back to her lair. (How would the Countess know where Mark's friends work, when Mark will be there, and when Robin will just happen to be in the parking lot, to kidnap her? I DON'T KNOW!!! And why wouldn't the Countess just bite Mark right there in the parking lot to get the third transfusion so she can continue to survive? I STILL DON'T KNOW! QUIT BOTHERING ME!!) Worse yet, there's been no progression leading up to this—she could have kidnapped Mark or Robin or whoever she wanted at any time in the story (not to mention when they're alone and nobody can stop her), but it's happening now because, well, just because the movie has to end. ¹—We had totally different visions for the film, but we never talked it through with him. The screenplay that Goldwyn bought dropped modern teens into a horror movie that played out in the setting of Hollywood, which was filled with bloodsuckers and out of virgins. Howard did the opposite with the script; it was what he helped do with Mork & Mindy: Take a fantasy character (a space alien in that show, and in our case, a vampire), move it out of its element, and drop it into the suburbs. Now, we deferred to Howard and definitely helped in that process, moving the scenes out of Hollywood over the course of two years' rewriting, but the Countess never left Hollywood in our original script—sort of a modernized Transylvania—and she lured Mark into her world, where she was in charge. Howard disagreed with that approach and wanted scenes of the Countess chasing Mark around Orange County (thus Sebastian's line about the Little Leaguers), which we argued was already the plot of Love at First Bite, right down to the big dance number, with the suburbs replacing New York City in a fish-out-of-water plot. It also made the story choppy and opened massive holes in the plot. In our original script, the Countess doesn't know where Mark lives and must lure him back to Hollywood through his dreams, and he can't resist that temptation; In the finished film, the Countess somehow knows where Mark lives and where he goes to school—and even where his girlfriend works (at a mall clothing store), and what time he'll be visiting her there. (How does she know Robin will make him try on sweaters in a changing booth—not to mention which booth he will go into? I DON'T KNOW.) She confronts Mark there, and decides that it would be the perfect moment to bite his inner thigh for a second time, while he's waiting for Robin to get him a new sweater... and then, after all that, she just LEAVES!!! (Why is the Countess leaving Mark in Orange County with the girlfriend he's trying to sleep with, when she still needs a third infusion of his virgin blood to survive??? Is it almost daylight? Is Robin wearing a cross? Are they serving too much garlic in the pizza at the food court next door? I DON'T KNOW.) Next, the Countess shows up at Mark's high school dance. (How does she know where the school is, what time the dance is, and why does she think this is a good time to bite him in front of a couple hundred witnesses? I DON'T KNOW!) The Countess and Robin then have a big showdown on the dance floor that turns into a dance-off—none of the faculty seem to care that an adult woman is attempting to stab one student and bite another—the Countess then... doesn't bite him and JUST LEAVES AGAIN!!! After she does that, the stalled plot that we wrote simply resumes on the dance floor, unchanged, with everybody ignoring what just happened and awarding Mark the "best costume" prize for slicking his hair back (i.e., being dressed as a vampire). You could literally pull the dance out of the story and nobody would know it was ever there. There's no cause and effect—it's just a set piece, dropped into the story for no particular reason. That kind of thing works much better in ten-minute sitcom intervals, between commercial breaks, than for 90 uninterrupted minutes onscreen in which you need the story to build, and for the audience to believe it, stay engaged, and root for or against the characters. The Countess just comes and goes for no particular reason, and it destroys the suspense, diffuses the feeling of being stalked or chased, negates all the urgency of the Halloween night ticking clock, and removes dramatic tension from the storyline (fancy theories for a dopey teen sex comedy, I know, but it matters). Finally, for the third and final bite, the Countess rides by limo to where Mark's friends work in Orange County (Sebastian is now reduced to being a driver with no lines) and she kidnaps... Robin (???), so that Mark (who watches all of this, a hundred feet away) will follow them back to her lair. (How would the Countess know where Mark's friends work, when Mark will be there, and when Robin will just happen to be in the parking lot, to kidnap her? I DON'T KNOW!!! And why wouldn't the Countess just bite Mark right there in the parking lot to get the third transfusion so she can continue to survive? I STILL DON'T KNOW! QUIT BOTHERING ME!!) Worse yet, there's been no progression leading up to this—she could have kidnapped Mark or Robin or whoever she wanted at any time in the story (not to mention when they're alone and nobody can stop her), but it's happening now because, well, just because the movie has to end.

This also created a severe tonal issue. We wanted more of a What We Do in the Shadows or Young Frankenstein-style authenticity to offset the humor, but they went in another direction. So we bent the plot to Howard's wishes, (e.g., moving the second bite from Hollywood to a house of mirrors in a run-down amusement park on the outskirts of Hollywood). Howard didn't fight us—he just let us noodle around with scenes he didn't want to shoot, and waited for us (and Dimitri and Robby, more importantly), to be gone—then did what he wanted without our arguing (e.g., moving the second bite from the house of mirrors at the run-down amusement park in Hollywood to a single mirror in a changing booth at a mall in Orange County). Then Howard went pretty much blameless when critics accused Dave and me of bad plotting, lazy storytelling, and ruining Cleavon Little's career.

²—In the case of Dave and I, it would take us many years of rewriting film scripts to realize that if a scene wasn't working, it was usually due to story problems, and you couldn't just throw more jokes and characters at it, to make it funnier (e.g., clumsy Otto)—because you'll actually stop the momentum and lose the audience. The secret was using cause and effect to propel the story forward in a way that was logical—seemingly inevitable—but not predictable (this doesn't happen enough in films because it's such hard, time-consuming work); an example of something we got right in this script would be staging the scene in the vampires' lair at the climax—the audience was expecting the cornered heroes to defeat the vampire by driving a stake into her heart, or breaking open a window and letting the morning light in, or some other horror movie trope (or even for the vampire to win, which happened in the first draft), but our final twist was that in the short minute it took for the vampires to break down the doors and catch up to our heroes in the lair, they had screwed in a bouncing, rattling coffin (a call-back to all the squeaking cars in the first scene)—so while it foils the vampires (who need a virgin, making Mark and Robin useless to them), it also connects the ending scene to the opening scene, bringing the story full-circle, and in doing so solves the initial conflict between Mark and Robin regarding pre-marital sex. Using those set-ups planted in the first few scenes, the resolution feels inevitable from a storytelling perspective, but the audience was still surprised (at least they were in 1985). I still have the Los Angeles Times review, calling it, "an elaborate ploy to motivate and justify Carrey's loss of virginity, and it's a maneuver so sly you have to smile upon recognizing it." I was so proud that we pulled that off, even if it took six drafts. (Plus, who can resist a premature ejaculation joke when it actually serves the plot?) I wish we would've/could've sat down with Howard and really worked through the entire script like that, instead of leaving him without a proper story, forcing him to lob Phone-a-Date clubs, transvestite jokes, ice cream trucks, faux-Indian booksellers, and scarf-stealing valets into the scenes to make them pointless, isolated set pieces that had nothing to do with the plot and couldn't resonate with the audience. ²—In the case of Dave and I, it would take us many years of rewriting film scripts to realize that if a scene wasn't working, it was usually due to story problems, and you couldn't just throw more jokes and characters at it, to make it funnier (e.g., clumsy Otto)—because you'll actually stop the momentum and lose the audience. The secret was using cause and effect to propel the story forward in a way that was logical—seemingly inevitable—but not predictable (this doesn't happen enough in films because it's such hard, time-consuming work); an example of something we got right in this script would be staging the scene in the vampires' lair at the climax—the audience was expecting the cornered heroes to defeat the vampire by driving a stake into her heart, or breaking open a window and letting the morning light in, or some other horror movie trope (or even for the vampire to win, which happened in the first draft), but our final twist was that in the short minute it took for the vampires to break down the doors and catch up to our heroes in the lair, they had screwed in a bouncing, rattling coffin (a call-back to all the squeaking cars in the first scene)—so while it foils the vampires (who need a virgin, making Mark and Robin useless to them), it also connects the ending scene to the opening scene, bringing the story full-circle, and in doing so solves the initial conflict between Mark and Robin regarding pre-marital sex. Using those set-ups planted in the first few scenes, the resolution feels inevitable from a storytelling perspective, but the audience was still surprised (at least they were in 1985). I still have the Los Angeles Times review, calling it, "an elaborate ploy to motivate and justify Carrey's loss of virginity, and it's a maneuver so sly you have to smile upon recognizing it." I was so proud that we pulled that off, even if it took six drafts. (Plus, who can resist a premature ejaculation joke when it actually serves the plot?) I wish we would've/could've sat down with Howard and really worked through the entire script like that, instead of leaving him without a proper story, forcing him to lob Phone-a-Date clubs, transvestite jokes, ice cream trucks, faux-Indian booksellers, and scarf-stealing valets into the scenes to make them pointless, isolated set pieces that had nothing to do with the plot and couldn't resonate with the audience.

³—We thought the Whisky would be perfect: a dark, musty club at the time—just the type we had in our script... but it had been converted into a brightly-lit "Phone-a-Date" club with doormen in uniforms and valet parking, full of well-dressed, middle-aged singles calling each other on lip-shaped telephones stationed at each table. (Dave and I saw this set and wondered if any of the filmmakers had actually been in a singles bar in the last 20 years; they definitely hadn't been to any in West Hollywood.) The other thing we noticed was that Howard had made the scene completely static. Nobody moved or conversed like they would in a real singles bar where people were trying to meet—they just sat at tables and talked over their lip-shaped phones (it played sort of like a Love, American Style gimmick, out of the '70s: "Love and the Phone Date" or "Love and the Vampire"). This made the scene easier to shoot, because everybody was sitting still for the camera instead of moving around and intermingling—but it was death to a movie in which you wanted action, and chemistry, and conflict; There was no interaction or eye contact; so now instead of Carrey walking up to the bar and meeting Hutton naturally, we had a needless expository section added in which the characters stared straight ahead and spoke into their phones, with lines like, "You're the woman at the bar in a black dress drinking a martini, and you'd like to meet with the one of us who is wearing a tan jacket and blue tie?" and, "She said to come on over!" Not much of a 'meet-cute.' ³—We thought the Whisky would be perfect: a dark, musty club at the time—just the type we had in our script... but it had been converted into a brightly-lit "Phone-a-Date" club with doormen in uniforms and valet parking, full of well-dressed, middle-aged singles calling each other on lip-shaped telephones stationed at each table. (Dave and I saw this set and wondered if any of the filmmakers had actually been in a singles bar in the last 20 years; they definitely hadn't been to any in West Hollywood.) The other thing we noticed was that Howard had made the scene completely static. Nobody moved or conversed like they would in a real singles bar where people were trying to meet—they just sat at tables and talked over their lip-shaped phones (it played sort of like a Love, American Style gimmick, out of the '70s: "Love and the Phone Date" or "Love and the Vampire"). This made the scene easier to shoot, because everybody was sitting still for the camera instead of moving around and intermingling—but it was death to a movie in which you wanted action, and chemistry, and conflict; There was no interaction or eye contact; so now instead of Carrey walking up to the bar and meeting Hutton naturally, we had a needless expository section added in which the characters stared straight ahead and spoke into their phones, with lines like, "You're the woman at the bar in a black dress drinking a martini, and you'd like to meet with the one of us who is wearing a tan jacket and blue tie?" and, "She said to come on over!" Not much of a 'meet-cute.'

| Our cast and crew disappeared after the film left theaters. |

|

⁴—What Howard doesn't include is that after Robby warned that the film would die, one of the other producers added, "You know Howard, if this film dies, you'll never get to direct another one." Howard then called him a "cocksucker," but guess which guy turned out to be more correct? (Advantage: cocksucker.) The truth is, nobody got any work after this film. It's looked back on kind of benignly now, its flaws easily forgiven, but it was critically reviled at the time... and though it opened at #1, the box office drop was STEEP (I still think we were just a couple laughs and 2-3 scares from an ongoing hit... and, yes, some decent vampire makeup would have helped... but it was what it was). Russ Thacher never got another movie made, and died in 1990; Hutton gave up features and started doing cheap TV movies and mini-series; Even Carrey needed another decade to right the ship, when he finally landed a job on In Living Color that turned things back around. (One of the producers recalled Carrey entering his office and screaming, "You ruined my career! Nobody will hire me!") Cleavon Little retreated to TV sitcoms like ALF and didn't get another movie until Fletch Lives, four years later; Karen Kopins was part of a failed Charlie's Angels TV re-boot, then became a stay-at-home mom; Skip Lackey became a game show host, then went into motivational speaking; and I have no idea what happened to the rest of the cast (when I look them up, many apparently went into real estate—all you need to know about show business is that California real estate is viewed as the safer, more stable career).

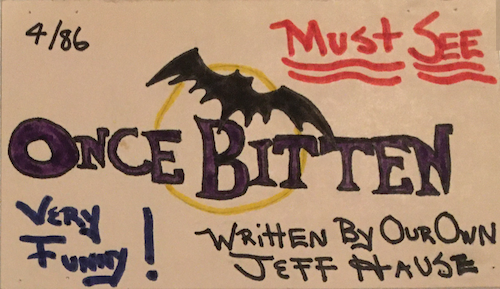

| The actual promo card on the "NEW RELEASES" video rack at the Licorice Pizza where I worked. |

|