Samuel John Goldwyn (7 Sep 1926 - 9 Jan 2015)

Samuel Goldwyn Jr. Dies at 88, by Carmel Dagan, Variety Staff Writer; January 9, 2015 8:52PM PT

Samuel Goldwyn Jr., the son of a fiercely independent-minded Hollywood mogul and the producer of many independent films in his own right including "Mystic Pizza" and studio hits including "Master and Commander," died Friday at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He was 88. His son John Goldwyn told the New York Times he died of congestive heart failure.

Goldwyn Jr. received his final credit as a producer, together with son John and others, on Fox's long-gestating remake of the Goldwyn Sr.-produced classic "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty," starring and directed by Ben Stiller and released in December 2013.

The courtly and soft-spoken scion was known for shepherding independent and foreign films and got his start in documentary filmmaking, in contrast to his brash father, who made his way from a youth of poverty in Poland to a partner in MGM.

"I love it. If you don't love this business, don't go near it. Don't go near it to get rich," he told Britain's the Independent in 2004. "And just remember, if you're right 51 per cent of the time in this business, you're a genius."

As producer of the Peter Weir-directed "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World" together with Weir and Duncan Henderson, Goldwyn Jr. shared that film's Oscar nomination for best picture in 2004. (The film received a total of 10 nominations and won two Oscars.)

After a failed merger and lawsuit resulting from MGM's acquisition of the distributor, Goldwyn Jr. relaunched his company as Samuel Goldwyn Films in the early 2000s. Though it was not nearly as active as the earlier incarnation, the new entity released indies such as "The Squid and the Whale," "2 Days in Paris" and "Robot & Frank."

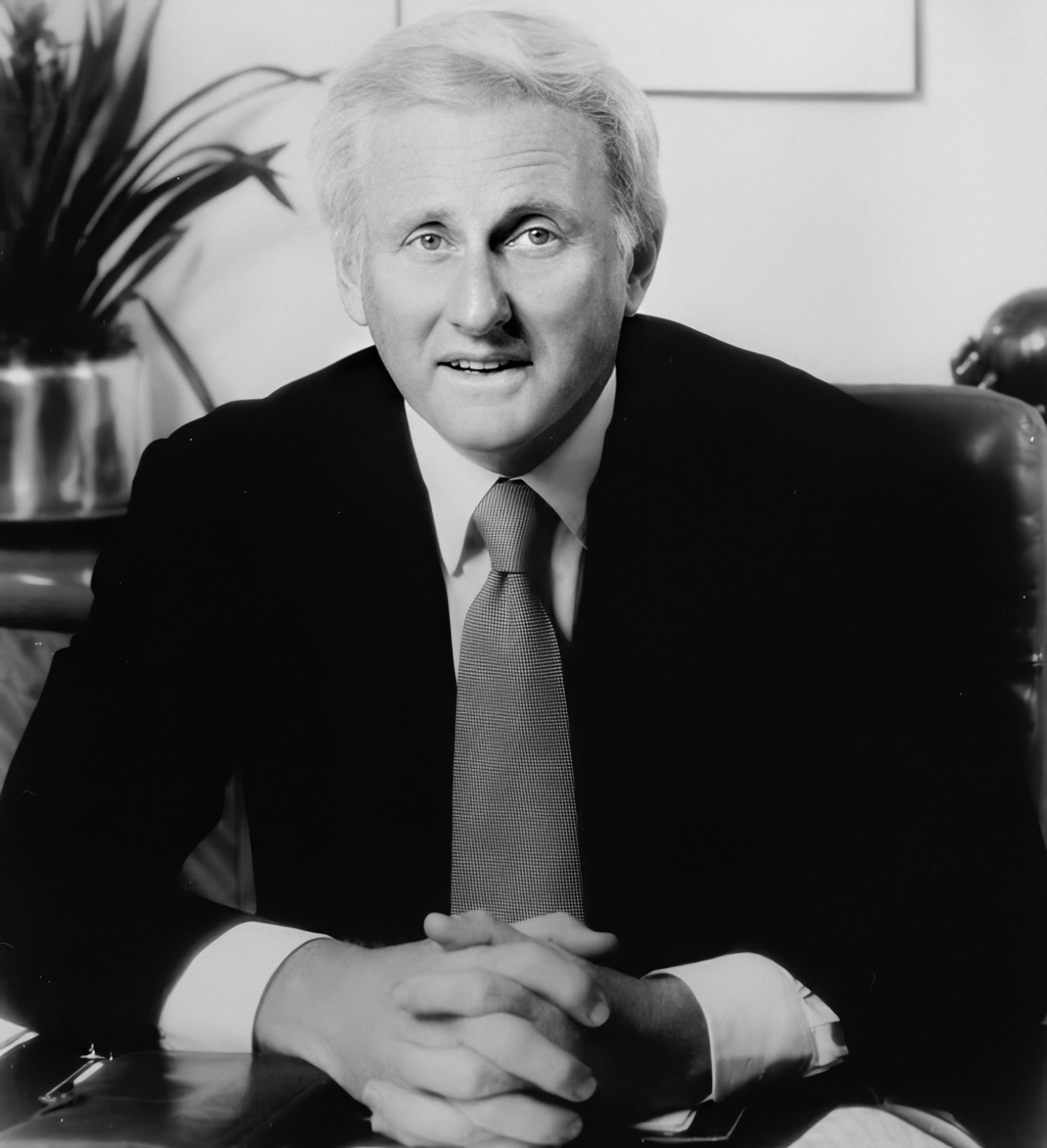

In a 2004 New York Times profile, the tall, silver-haired Goldwyn was described as resembling not so much his father "as a combination of Kirk Douglas and Paul Newman."

But Goldwyn Jr. gloried in his father's achievements, eventually returning to live as an adult in the vast Beverly Hills estate built by his father and tending to the library of films. The films Samuel Goldwyn Sr. produced, including "The Best Years of Our Lives" and "Guys and Dolls," are handled by the Samuel Goldwyn Jr. Family Trust and currently licensed to Warner Bros. for U.S. distribution.

Sam Goldwyn Sr. was one of the pioneers of Hollywood, and his production company, Goldwyn Pictures Corp., became part of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1924, but Goldwyn Sr. had no involvement with MGM and was independent of the studio system after that.

Goldwyn Jr., however, did not "trade on his father's name," Tom Rothman, who began his career at the Samuel Goldwyn Company, told the New York Times.

Goldwyn Jr. grew up in Los Angeles as a self-confessed "Hollywood brat"—his mother was actress Frances Howard, he attended his first Oscar ceremony at age 11 and worked in editing rooms during summer vacation. He then spent a long period away from Los Angeles, attending prep school in Colorado and the U. of Virginia. After serving in the Army, he then took a job in England working for J. Arthur Rank, where he earned his first film credit as associate producer on the British crime thriller "Good-Time Girl," Diana Dors' first film, in 1948. Goldwyn Jr. rejoined the military in 1950, where he produced and directed documentaries for the staff of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Back in the U.S., he worked under Edward R. Murrow at CBS News and co-produced docu series "Adventure."

When the young Goldwyn returned to Hollywood in the mid-1950s, Goldwyn Sr.'s career was in decline. In 1955 Goldwyn Jr. launched his production company Formosa Prods. (his father's Samuel Goldwyn Studio was located at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Formosa Avenue) and produced his first film, uncredited, the same year: the Robert Mitchum Western "Man With the Gun."

Via Formosa Prods. he also produced "The Sharkfighters" (1956), "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" (1960) and, in the early 1970s, "Cotton Comes to Harlem" and "Come Back, Charleston Blue." Goldwyn Jr. directed one film, "The Young Lovers," starring Peter Fonda and Sharon Hugueny, in 1964.

In addition to his film work, Goldwyn Jr. produced the Academy Awards ceremony twice, in the late 1980s, winning an Emmy in 1988 for his effort.

His family's charitable contributions are evident throughout the city: Samuel Goldwyn Foundation sponsors the yearly Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards, created the Samuel Goldwyn Foundation Children's Center day care facility, built the Academy of Motion Pictures theater and constructed the Hollywood Public Library in memory of Frances Howard Goldwyn.

He was married three times, to writer Peggy Elliott, with whom he had two children, and to actress Jennifer Howard, with whom he had four. He is survived by his current wife Patricia Strawn; four sons, producer John; actor Tony; Francis, and Peter, senior VP of Samuel Goldwyn Films; and two daughters Catherine, and Elizabeth; and nine grandchildren.

(Pat Saperstein contributed to this report.)

Samuel Goldwyn, Jr.: 1926 - 2015

by Once Bitten co-writer David Hines, January 10, 2015

Samuel Goldwyn, Jr.—the man who produced and financed our first film, Once Bitten—passed away today at the age of 88.

Shit.

You've heard me bitch about various aspects of my experience on Once Bitten, and no doubt will again.

But you've never heard me bitch about Samuel Goldwyn, Jr. While I certainly didn't always agree with him (as a snot-nosed 22-year old), I recognized that Mr. Goldwyn always treated us kindly and fairly. Frankly, Jeff and I still get royalty checks to this day because he saw to it.

He was a good and decent man to a couple of greenhorn screenwriters who I guarantee were more trouble than we were worth. He took a big gamble on us, didn't fire us when he had every right to after we turned in a terrible second draft, and gave us the experience of having written a movie that debuted at #1 at the box office. He gave us our start, our first credit, and an amazing experience. I'll always love him for that.

Safe journey, sir. And I'm really, really sorry I yelled at you at the Friar's Club that time.

But more than anything, thank you, thank you, thank you.

Dan Perri's Title Design Blog: The Samuel Goldwyn Film Logo

Film Title Sequence Designs and Adventures of Dan Perri.

August 25, 2017 ~ Dan Perri

Quite early in my career I worked on many independent non-studio films. Along the way I worked with an old time publicist who had been in the business for a very long time.

This guy had worked for the original Sam Goldwyn at The Goldwyn Studios as his personal publicist for many years. Well, when the famed movie mogul died in 1974, the industry wondered what would become of his film studio in the heart of Hollywood.

There was rumor that Goldwyn's son, Sam Jr. wasn't interested in running the company, so, in early 1975 it was a surprise when Sam Jr. did take over his father's storied film studio and moved into his huge, second story corner office overlooking Santa Monica Blvd. in Hollywood.

So, it was there that I was summoned to a meeting at by Mr. Goldwyn Sr's old time publicist to meet Sam Jr. and offer design ideas for a new, modern Samuel Goldwyn Studios film logo that would be at the beginning of all Goldwyn releases.

After a brief and pleasant greeting and quick once over, Sam Jr. gave me the green light to bring him some ideas on how to represent his dad's company in the 1970s, effectively updating the old, somewhat stodgy formal type treatment that was the Goldwyn logo since the late 1930s.

The following week I came storming into his office with a whole pack of different ideas. Original and modern and—in my mind—great solutions to his unique problem.

Well, after exhaustive pitches and descriptions on how to treat each idea on the screen it became clear that Sam Jr. didn't seem to want contemporary modern ideas because he had rejected every single one that I'd presented to him.

With shared disappointment he thanked me and I turned to the door to leave. But, just as I approached the door an idea stopped me in my tracks. I threw it over my shoulder in a rapid fire description thinking that he could use it without any of my involvement, since to me it seemed so simple and by this time obvious. That was to see Samuel Goldwyn's signature being written on the screen.

Sam suddenly lit up. He loved it and immediately asked me to go and design it and bring it back. Excitedly, I shot out of there and went back to my little, tiny office nearby to create this title treatment that was to live on to this day and still be used by The Samuel Goldwyn company.

I returned with all of these storyboards. Different ideas seeing an elegant fountain pen come into frame and smoothly glide across the screen leaving behind a fountain pen script of the signature. Another of seeing a hand holding a fountain pen move into frame and write the name across the screen.

With each idea I would always start by referring to Sam's dad's signature and how it would come on. But as soon as I mentioned Sam's dad, Sam Jr. grabbed my arm and stopped me. Almost angrily he said, "Wait a minute, Dan, this isn't going to be my Dad's signature, this is going to be MY signature."

Suddenly I realized why he was so high on the signature idea. It would allow him to put his own actual stamp on the company. And it would modernize and perpetuate his father’s name all at the same time. It was a perfect design solution.

We finally arrived at the essence of the concept: a simple, white, elegant script that invisibly writes on the name in smooth, real-time strokes from an invisible pen.

When I returned to receive the actual signature to animate the finished film title from, Sam handed me a big stack of pages. I saw where he had written his name over and over until he got how he wanted it to look. Together we chose the final version and I went off to create the film elements to film the final screen version.

Since it was to be on the screen as its primary application, it had to be white against a black screen. This was done because of how the beginning of film reels usually gets very scratched and if it were black on white it would soon look like black on a field of little hairy scratches and endless bits of dirt. White on black would also be much more elegant. As it turned out, Sam opted for a medium dark blue background, instead.

I hand animated each frame with a series of 'reveal' mattes laid over a film cel of the actual signature, backlit photographed on an animation camera stand.

After creating the actual film elements I then had to create a theatrical widescreen version, a normal 16:9—originally known as 1.85—theatrical version and a television version—known as 1.33—of the logo so it could be integrated into both old and new films and TV versions.

Sam also wanted a full complement of printed materials for office use proudly displaying his actual signature. I have always been very pleased with its usage and Sam—until his death—never failed to thank me for creating it every time I saw him.

(Dan Perri has been designing titles for major motion pictures for decades. He has designed hundreds of titles for the most influential films that have now become iconic and is still an active designer. From 'Star Wars' to 'In the Valley of Elah', Dan continues to shape the industry title sequences.)

Liz Goldwyn Remembers When the Oscars Were Her Playground

Growing up as showbiz royalty, the filmmaker, artist, and writer remembers the days when she roamed the Oscars rehearsals with free rein.

by Liz Goldwyn for Vanity Fair; February 15, 2016

My father, movie producer Samuel Goldwyn Jr., produced the Academy Awards for two years running, in 1987 and again in 1988, for which he won an Emmy. He looked every inch the "Hollywood producer" in his Savile Row suits, a blue-and-white striped Turnbull & Asser shirt, 60s aviator glasses—a silver fox. I didn't yet have his sense of style. I was an awkward 10-year-old when he started rehearsals for the '87 awards—with a bad perm and too short bangs I'd cut myself. Hollywood was my backyard, not the high-school cafeteria run by the football team I would later know it to be.

My brother Peter and I treated the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, in downtown Los Angeles, where the ceremony was held, as our personal playground; we ran rampant through the corridors and basement, up and down the lushly carpeted grand staircase, killing time while our father ran through the show. We had free rein to explore, as long as we didn't get in anyone's way or make trouble. Much of my childhood I remember like this—being in the most fabulous places with extraordinary people, more concerned with stealing sugar packets from dining tables and playing hide-and-seek.

Dad gave Peter and me autograph books to use during rehearsals, so we could collect the names of the nominees and presenters. It was a game for us—whoever collected the most achieved superiority. I still have mine—brown leather with gilt lettering, the pages now brittle and loose. I keep it on my bookshelf, a snapshot of an in-between time in Hollywood. The auditorium was filled with blockbuster stars of the day and the last of the golden-era leading ladies and men, who showed up for my dad to present on the show, out of respect for him and their long relationships with my grandfather—Samuel Goldwyn—with whom many of them had worked and played. Audrey Hepburn, Jennifer Jones, Gregory Peck, Elizabeth Taylor...

Peter and I were too young to know who these legends were—or to be intimidated by their star power. We were more interested in when RoboCop and Pee-wee Herman showed up for rehearsal. I look at family photos my mother took—Robin Williams giving Peter a noogie for good luck on the steps of the stage; me posed stiffly next to Oprah Winfrey in a dressing room—and cringe at how lucky and ignorant I was, but back then it was nothing more than visiting Dad at the office.

I had never seen my father nervous before—that is, until an old lady showed up for rehearsal. She was quickly ushered backstage. Dad pulled me aside and insisted I go with him to greet her. My father and I stood outside the closed door of her dressing room. He cleared his throat and hesitated before knocking. Entering, I was practically blinded by the bright lights surrounding her makeup mirrors. She sat with her back to us with an enormous jar of Pan-Cake makeup in front of her. She chatted with my father while scooping her hand into the jar, slathering foundation over wrinkled skin. I watched, transfixed, not adding much to the conversation. My father gave me a nudge and whispered, "Go on—ask for her autograph, Lizzie." I did what I was told, eager to get back out into the theater, worrying that Peter had already collected more signatures than I.

Almost bowing deferentially, my father and I exited, and he closed the door behind him. I could tell he was annoyed with my impatience. "Don't you realize that you were just in the presence of greatness? Show some respect." I looked down at my autograph book, at the looping Magic Marker scrawl, dumbstruck even now—"Hello to Liz, Bette Davis."

|