|

"RING-TAILED ROARER"

Davy Crockett On Stump, Stage and Screen

Excerpts from the upcoming book by Jeff Hause

"Almost all non-literate mythology has a trickster-hero of some kind. ... And there's a very special property in the trickster: he always breaks in, just as the unconscious does, to trip up the rational situation. He's both a fool and someone who's beyond the system. And the trickster represents all those possibilities of life that your mind hasn't decided it wants to deal with. The mind structures a lifestyle, and the fool or trickster represents another whole range of possibilities. He doesn't respect the values that you've set up for yourself, and smashes them."

—Joseph Campbell, interviewed by Michael Toms in "An Open Life" |

"Movies are hardly ever about what they seem to be about. Look at a movie that a lot of people love, and you will find something profound, no matter how silly the film may be."

—Roger Ebert, "Life Itself" |

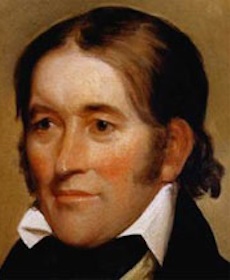

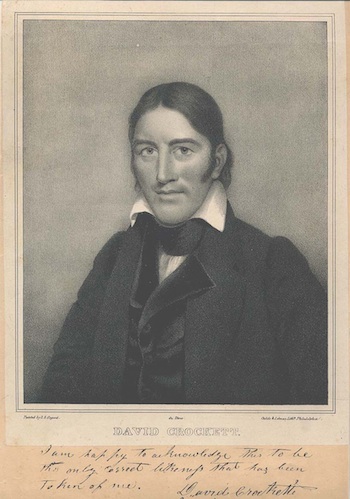

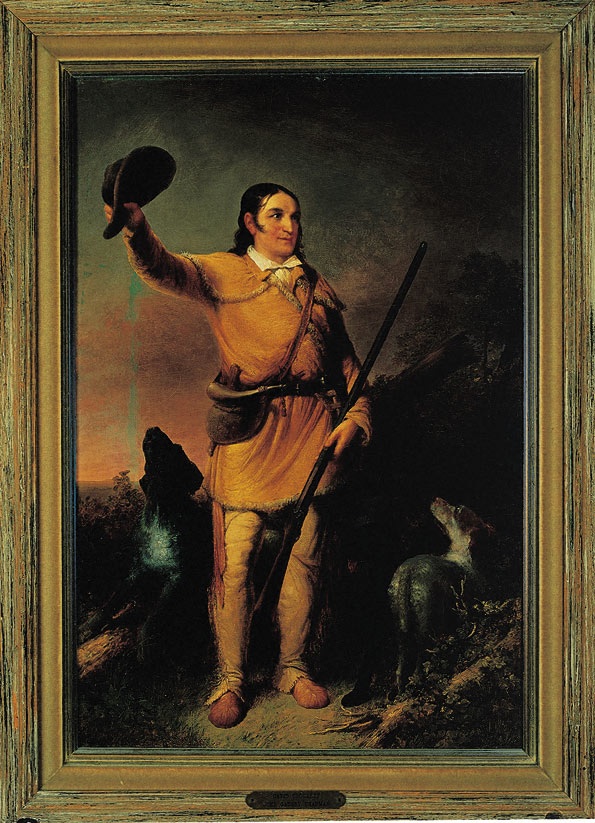

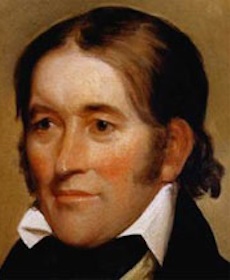

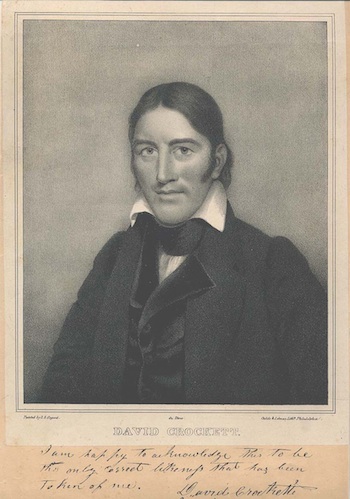

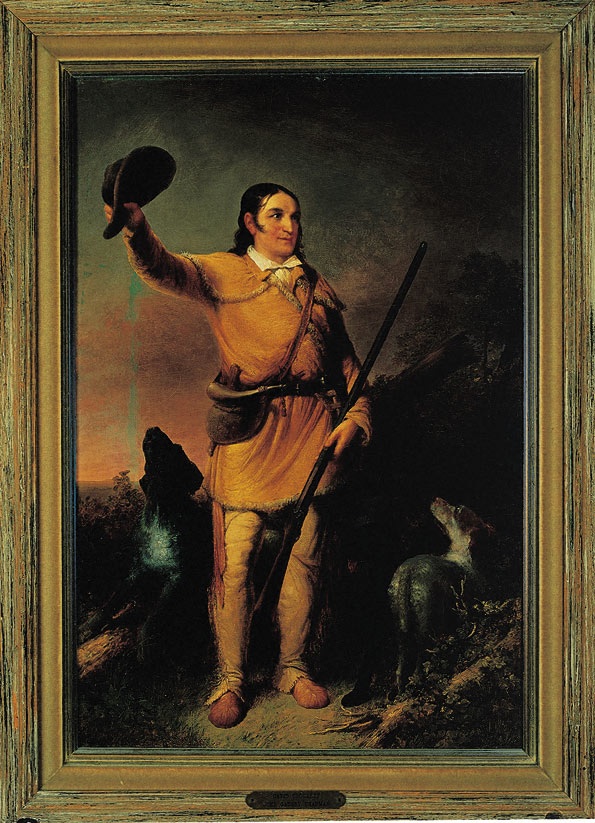

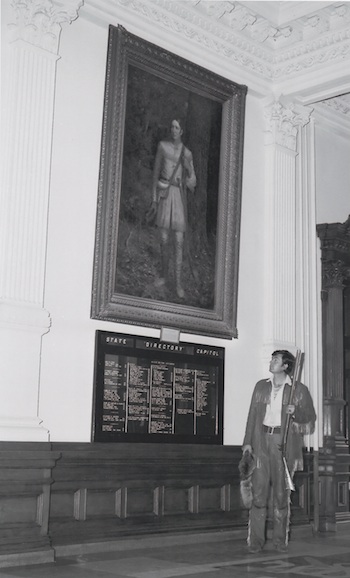

Portrait of David Crockett (1786-1836) painted by S.S. Osgood. Writing at bottom with signature and inscription: "I am happy to acknowledge this to be the only correct likeness that has been taken of me." Image: Tennessee State Library and Archives, 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, TN 37243. |

David Crockett was born first on August 17, 1786, in North Carolina, near the mouth of Limestone Creek on the Nolichucky River—the fifth son to John and Rebecca Crockett. I wrote "born first," because several decades later, he was born again—this time to "Davy Crockett senior," who could "grin a hail storm into sunshine," and his momma, who could "jump a seven rail fence backwards and dance a hole through a double oak floor." This Crockett was raised in cradle made from the "12-foot shell of a 600-pound snapping turtle," varnished with the oil of fifteen rattlesnakes, and covered in wildcat skins! A hundred years later, Crockett was born yet again—this time on a mountaintop in Tennessee, and he "kilt him a bear when he was only three." The first scenario is biographical fact, the second is taken from an almanac written twenty years after the first Crockett's death, and the last was written into a film script during the mid-20th Century, at the dawn of the New Frontier. All are as truthful as they need to be.

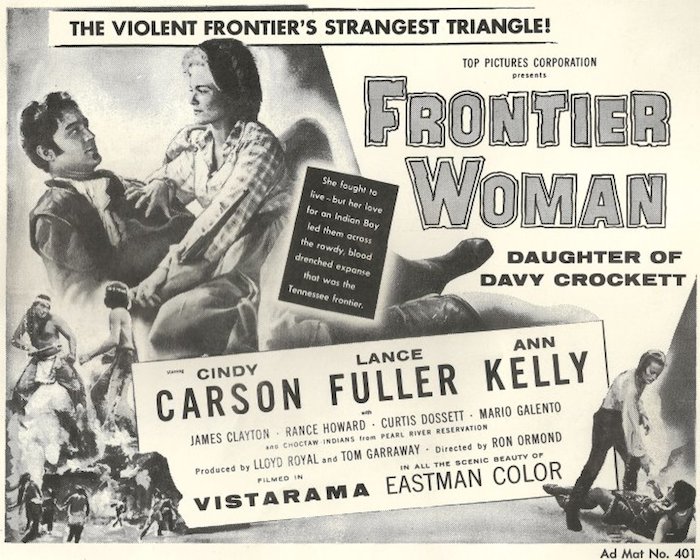

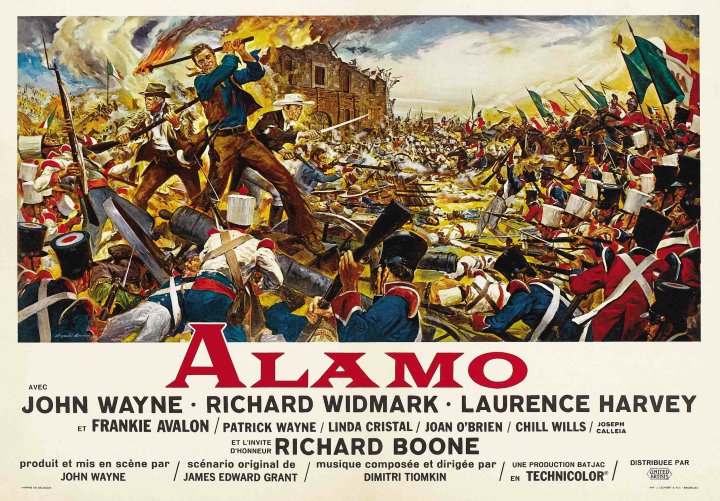

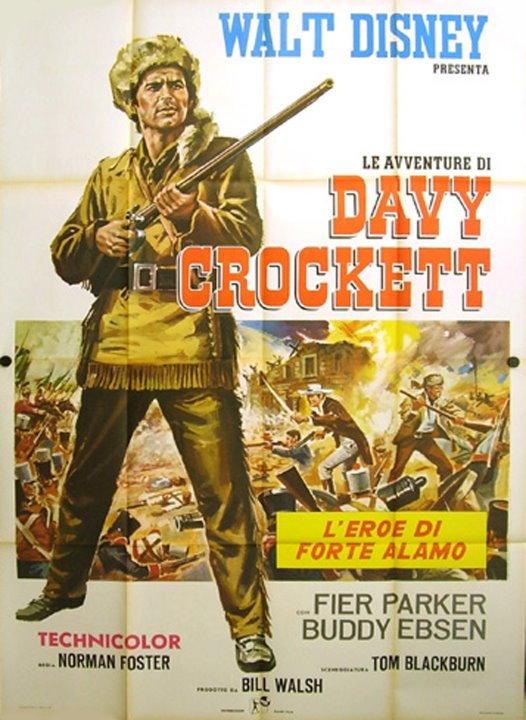

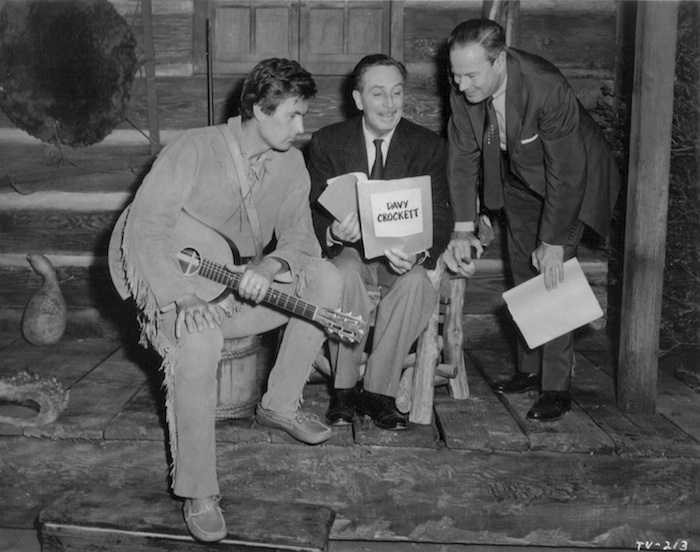

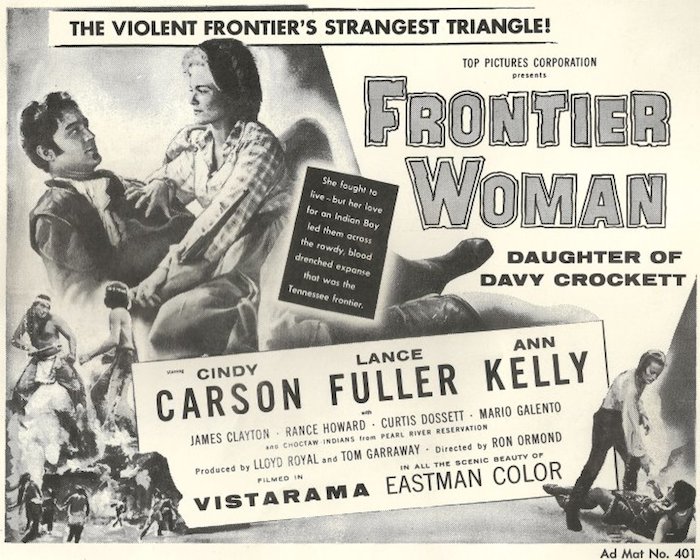

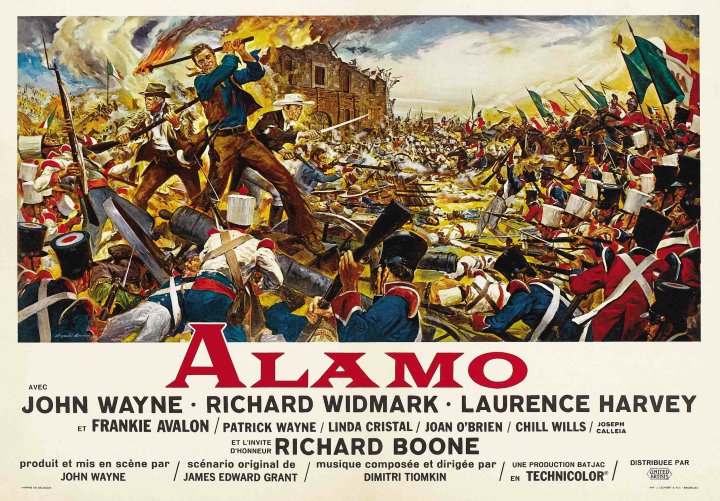

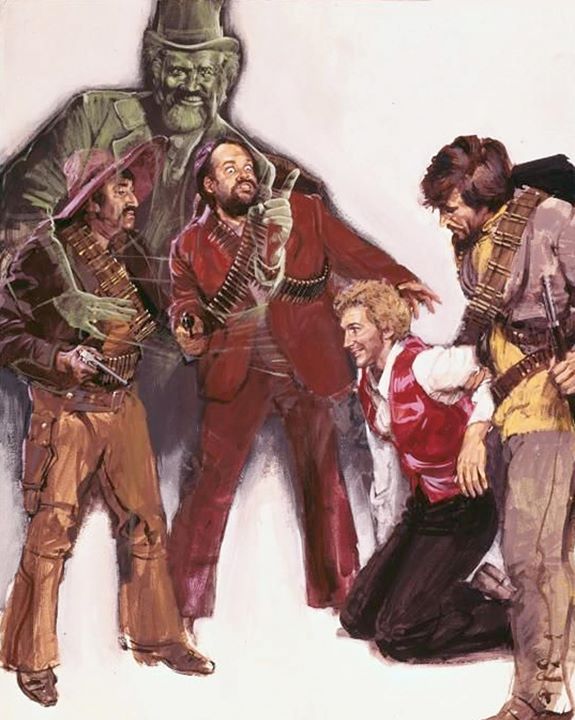

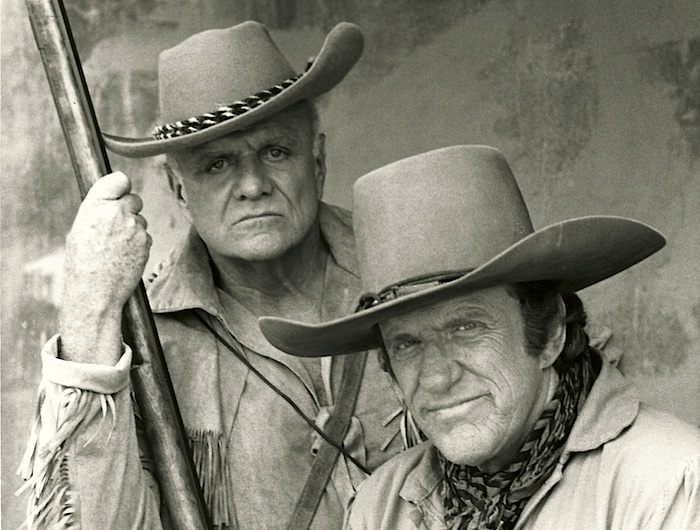

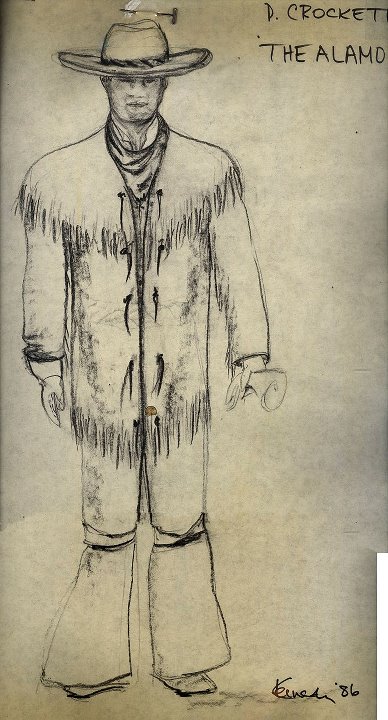

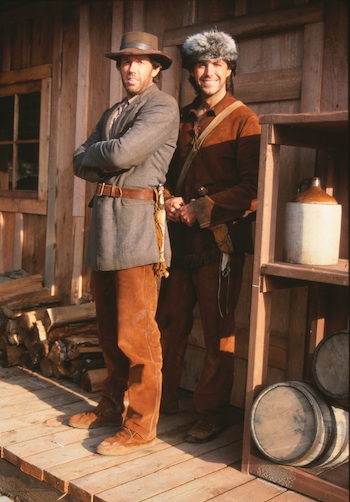

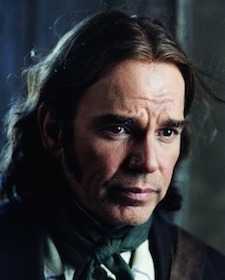

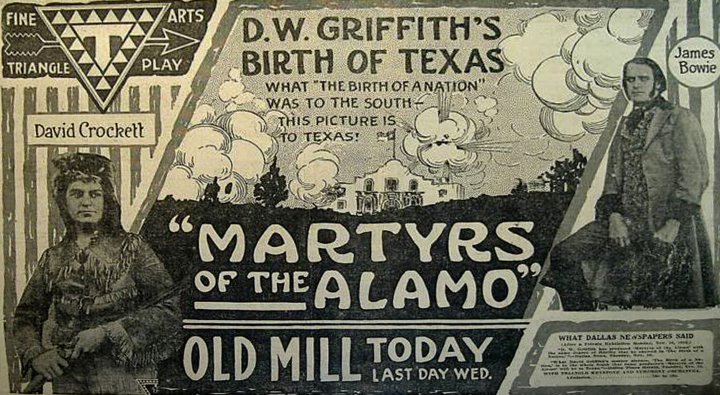

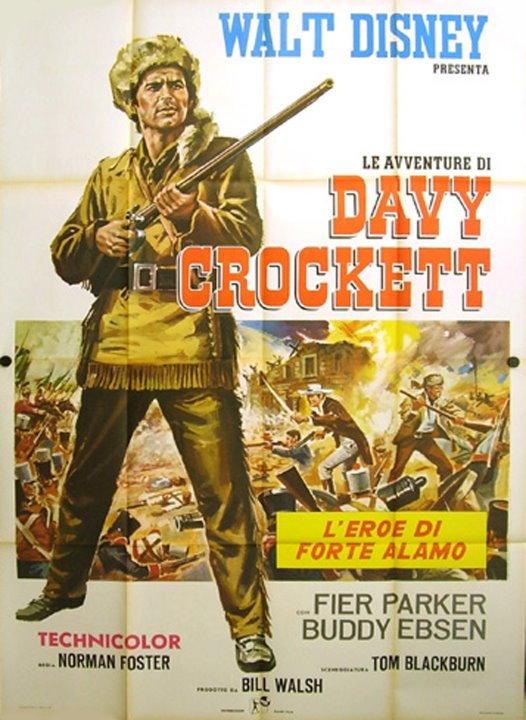

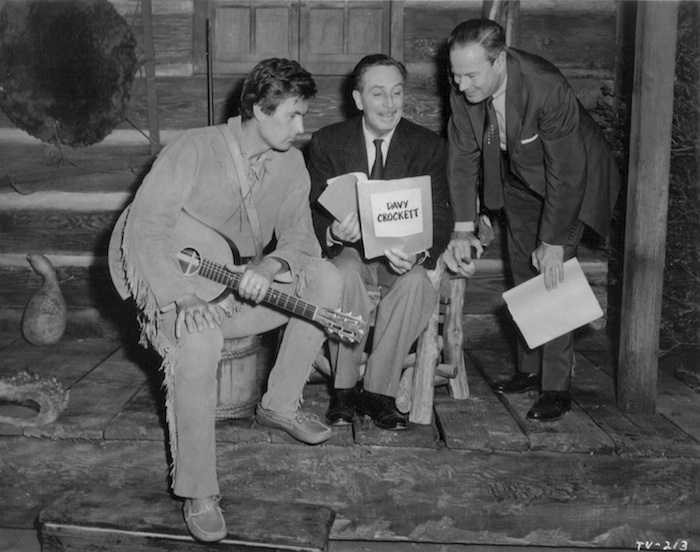

The real David "Davy" Crockett was a soldier, a U.S. Congressman, and died heroically at the Alamo, but his greatest contribution to the American culture was that he inspired the first truly unique, nationally-recognized comic character. The real Crockett was brash, cocksure and adventurous, and he symbolized the ever-expanding West. Since then, however, Crockett has been portrayed in remarkably diverse ways—interpreted by succeeding generations in terms that made sense to those particular times. As a result, each "Davy" representation will tell you more about the period the portrayal was created in than about the real David: In the years after his death, Crockett lost his anti-Jackson political affiliations and was characterized as a brash, uncouth "yaller flower o' the forest"—based on a fiction that the real Crockett helped popularize. Then in the latter part of that century, as the frontier began to disappear, Davy became a sentimental figure—a noble, illiterate backwoodsman still living with his mother. In the Twentieth Century, Davy kept the world safe for white women in producer D.W. Griffith's racist Alamo silent picture... and then Disney came along and cleaned him up for the kids. After that, John Wayne made him political again, even gave him a Mexican love interest, and played him as, well, John Wayne; Brian Keith played him as... well, I have no idea what Brian Keith was thinking. In 2004, Billy Bob Thornton's Davy was seen as a man trapped in a fiction; a celebrity Crockett for the star-obsessed twenty-first Century when people were just 'famous for being famous'.

As Michael A. Lofaro put it on Crockett's 200th birthday: "One of the primary reasons that assures the continuance of Davy Crockett as a quintessential American hero is his ability to be nearly all things to all people. So great a quantity of primary material from the popular press and media exists that when eager readers or critics delve into the various 'autobiographies,' tall tales in newspapers and especially almanacs, dime novels, plays, movies, and television shows, they invariably manage to discover a good deal of evidence to support the virtues or vices, the significance or lack of it, that they think or hope they might find in his character."

This book considers the evolution of Crockett in performance. Most enduring fictional characters change with the actor and the times. But David Crockett was real, and different aspects of the actual man were exploited or discarded with each succeeding generation over the course of 200 years—nearly the entire history of the United States. Some portrayals, like Fess Parker's and John Wayne's, became sensations and their characterizations say a lot about the culture of the time. Of course there will be portrayals listed in this book that didn't catch on—but that says something about the culture of the time, too.

The real David Crockett's story ended on a cold morning in 1836—but his legend has proven to be much more resilient, and much more malleable to fit the times. Therefore, this isn't just the story of David Crockett—this is the story of a country, and of us.

1: THE STUMP

"When I set out electioneering, I would go prepared to put every man on as good footing when I left him as when I found him. I would therefore have me a large buckskin hunting shirt made, with a couple of pockets holding about a peck each ... in one I would carry a big twist of tobacco, and in the other my bottle of liquor; for I knowed when I met a man and offered him a dram, he would throw out his quid of tobacco to take one, and after he had taken his horn, I would out with my twist and give him another chaw. And in this way he would not be worse off than when I found him; and I would be sure to leave him in a first-rate good humour."

—"A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee" by David Crockett (with Thomas Chilton) |

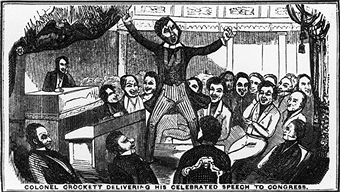

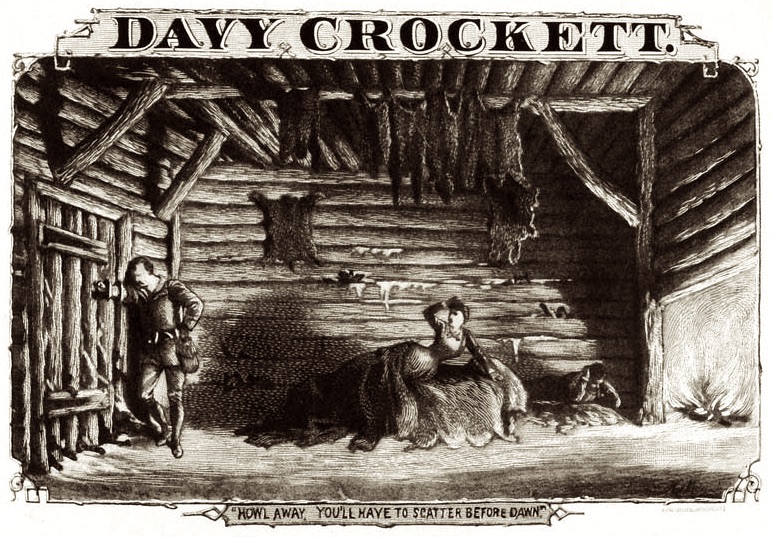

Image from "Life of Davy Crockett, the original humorist and irrepressible backwoodsman." Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1865. |

The first person to play Davy Crockett onstage was... well, Crockett himself. Therefore, any examination of the growth of the legend must begin with the real man—or at least the man Crockett portrayed.

A poor farmer (but a great hunter), he told tall tales about himself and became famous enough to get elected to Congress three times.

David first campaigned for the Tennessee state legislature in 1821. At debates, he always waited to speak until after his opponents, so that he could learn the local issues on the fly. If he was forced to talk first, he would tells a few jokes, then invite everyone to the nearest bar—with the drinks on him. (This is a tactic he would employ many times during his political career.)

In 1823, David was convinced to run again for the legislature in a much larger district, and was looking for a hook in order to reach more voters and make a name for himself. Crockett reinvented himself politically as a wild backwoodsman. He claimed to be "half-horse and half-alligator," and that he waded the Mississippi with a steamboat on his back. "I don't want it understood that I have come electioneering. I have just crept out of the cane, to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks," David said.

David was easily elected, now representing ten different counties. Known throughout the state, David was urged to run for the U.S. Congress.

A better-funded opponent narrowly beat Crockett in the next election, so he attempted to improve his financial lot and started a stave business. Between bear hunts in the spring of 1826, David attempted to run two boats of 30,000 staves to New Orleans, but they sank in the Mississippi River. Crockett was nearly drowned, until pulled from below deck of the sinking ship. Stranded in Memphis, David met wealthy Marcus B. Winchester,¹ who took immediately to David and urged him to run for Congress again. Winchester bankrolled Crockett's next political campaign with a loan of $250. While electioneering, Crockett began using the "brag and boast" hyperboles of the Mississippi flatboatmen that he had met while operating the stave business. He appeared all over the state, stumping with his usual tales of grinning animals to death and jumping rivers. David's opponent, Colonel John W. Cooke, attacked David on the grounds of decency (namely drunkenness and adultery). But for every charge Cooke made, David would make up a worse charge about Cooke. Eventually, Cooke planned to trap Crockett by presenting witnesses to refute him at their next debate. At the event, Crockett stepped up first, out-doing himself with slanderous accusations, then starts to sit... but suddenly he stepped back onstage, announcing that he knew his opponent was planning to trap him: "Fellow citizens, I did lie. They told stories on me, and I wanted to show them, if it came to that, that I could tell a bigger lie than they could. Yes, fellow citizens, I can run faster, walk longer, leap higher, speak better, and tell more and bigger lies about my competitor, and all his friends, any day of his life!" David then proposed that both sides drop all the accusations, and invited the crowd to the local tavern for a drink before Cooke could rebut, leaving to cheers. Cooke withdrew from the race, saying he would not consent to represent people who would applaud an acknowledged liar.

So in 1827, David was elected the House of Representatives, serving in the Twentieth Congress. The Jackson Gazette reported that he, quote, "arrived in Washington City on the 8th day of Dec. and took his seat. It was reported before his arrival there, that he was wading the Ohio towing a disabled steamboat and two keels." (In reality, Crockett arrived in Washington after a recurrence of malaria. Several bloodlettings, the accepted frontier cure at the time, left him in worse health than the sickness.)

David's rustic appearance caused a buzz in Washington. He was ridiculed by his political enemies as a vulgarian. Rumors even circulated that he mistakenly drank out of a finger bowl at a White House dinner for President Adams—which became so talked about that he had to have it rebutted in newspapers. But a strange response occurred: The attacks made David more popular! The generation of Americans inheriting the country from the Founding Fathers, the first to be born in an independent nation, was looking for a new kind of hero to represent that independence. David, the trash-talking son of poor squatters who had risen to the heights of Congress, became the confident, outspoken symbol of the new society—using the distinctively bawdy, humorous language of the frontier. Politics would never be the same.

David's notoriety and political career were still growing (he was called the "gentleman from the cane" as an insult, but it caught on). His main ambition in Congress was to pass a land bill that would help the poor squatters in his constituency obtain land for a reasonable price, by allowing for transfer of the federal lands in Tennessee to state control—and their sale by the state to the public at pennies on the dollar. But Crockett found it hard to navigate the back-room games and compromises in Washington, and the bill stalled.

In 1829, Crockett was re-elected to serve in the Twenty-first Congress while his general in the Creek War, Andrew Jackson, was elected President. Promoting himself as the leader of the common man, Jackson invited "the people" to eat at the White House and celebrate his victory. To Jackson's regret, thousands of revelers swarmed into the White House, wrecking furniture, smashing several thousand dollars worth of china and glassware, and generally destroying the place. Finally, to draw the crowd outside, tubs of liquor were placed on the lawn. Jackson snuck out of the place through a back window. He then slept in a hotel while repairs were made to the residence. While it isn't known if Crockett attended, it wouldn't be surprising if he did.

While Jackson was sleeping in that hotel, Crockett took up residence at the boarding house of Mary Ball. Boarding houses were a common dwelling for 19th-Century politicians to eat and sleep. Congressmen typically chose which Capitol Hill boarding house they would lodge in based on their state or on their political affiliation, and these groups were known as "messes." Crockett was lodged in the same room at Mary Ball's as a new Representative from Kentucky, named Thomas Chilton (1798-1854). The two men rapidly became friends and would spend the better part of the next six years as political allies, and Chilton would be instrumental in the creation of the Crockett legend.²

"I have no other feelings towards Colonel Crockett than those of pity for his folly."

—James K. Polk |

Image from a Crockett Almanac |

On May 19, 1830, David proved his independent nature—being independent both of political parties and his constituents: He spoke out fiercely against President Jackson's 'Indian removal bill'—virtually the only Congressman to do so. The bill was to move all Native Americans from their homes, to lands west of the Mississippi. But Crockett represented many Indians who had settled in his districts and even married into established families. In a speech to Congress on May 19, 1830, according to the record: "Mr. C said that four counties of his district bordered on the Chickasaw Country. He knew many of their tribe; and nothing should ever induce him to vote to drive them west of the Mississippi." Disgusted by the government's handling of Native Americans, David said that he had remained a Jackson man—even though Jackson hadn't, and declared he would "set up shop for himself." Still, David had to suppress the record of his speech, because his constituency (most of who want the cheap Indian land as well) was for Jackson and the bill.

In 1831, David ran for reelection, and the Jackson political machine set out to destroy him: They successfully conspired to table his land bill in Congress (thus destroying the dreams of many of their own citizens in the process, but hey—that's politics), then published his speech against Indian removal all over the state. "It would seem that the sufferings of a hungering people excites no pity with our President," Crockett wrote in a February 1831 campaign circular, "and that all the miseries of famine, brought on by his own acts, are to be used as the instruments for their extermination or removal."

David fought back as best he could as he ran for re-election, but the attacks were fierce. The Missouri Republican newspaper printed this supposed campaign speech by David: "Friends, fellow citizens, brothers and sisters: Governor Carrol's a statesman—Jackson's a hero and Crockett's a horse!!! . . . they accuse me of adultery, its a lie. I never ran away with any man's wife that wasn't willing in my life. They accuse me of gambling; it's a lie—for I always plank the cash. Finally . . ., they accuse me of being a drunkard; it's a damned lie, for whisky can't make me drunk!"

During the course of these attacks against his ethics, David seems to have lost his most valuable asset—his sense of humor. In Paris, Tennessee, he threatened to thrash political opponent William Fitzgerald in public for saying that he rarely showed up for roll calls in Congress. Fitzgerald stood to speak, saying he'd prove his charges, and Crockett angrily rushed the stage to fight. In response, Fitzgerald pulled a pistol from under a handkerchief, aiming it at Crockett's chest. Crockett sat back down, humiliated in front of the large crowd. While it was probably a smart move for David to back down, it wasn't what the public expected or even wanted to see from "Davy."

So, very un-heroically, David lost the election—due to both his opposition to Indian removal and his support for high tariffs and for internal improvements (sorry, all you Conservative Davy-lovers who think he stood for smaller government)—all highly unpopular in Tennessee . . . And along with his loss, Tennessee citizens continued to lose their land, the 'Indian bill' passed, and the Trail of Tears began. Driven out of Congress and still deeply in debt, David went home—a failure once more.

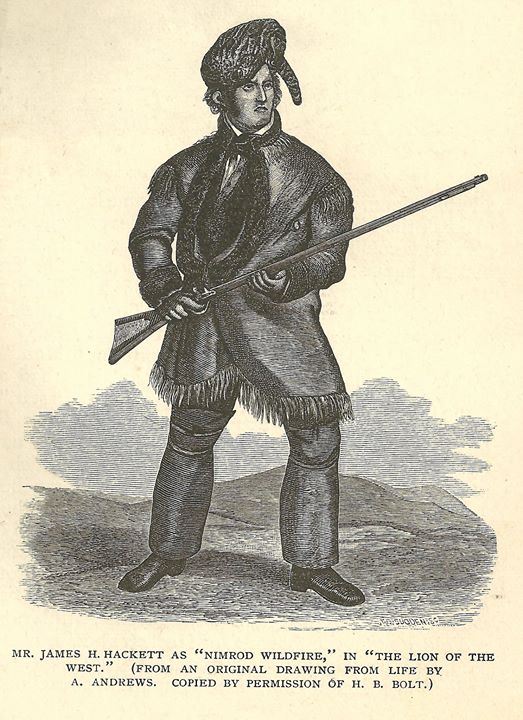

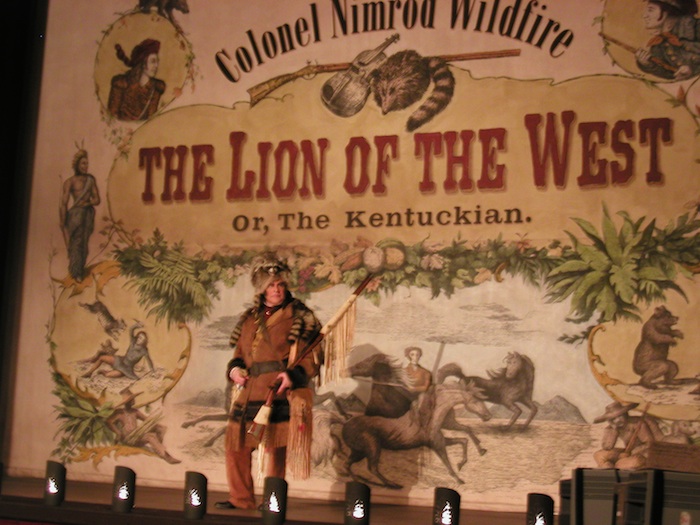

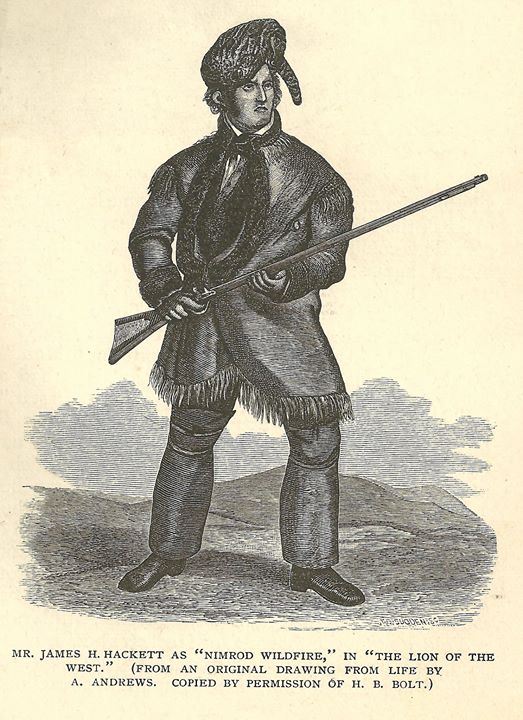

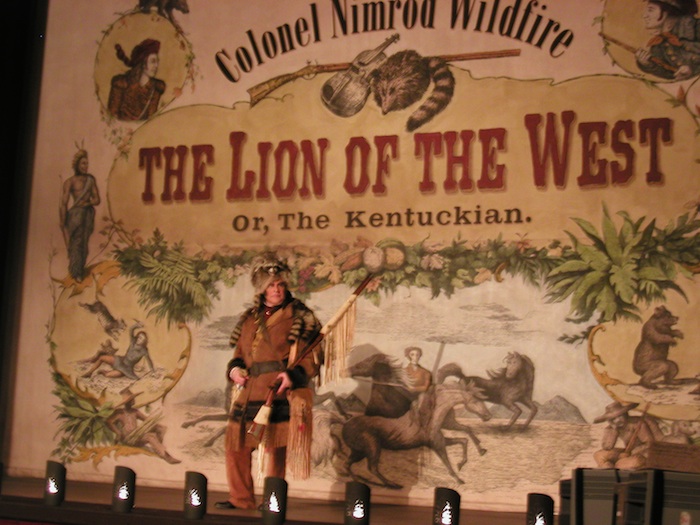

While "Old Hickory Face" had driven David out of office, he was not out of the public's eye. On April 25, 1831, James Kirke Paulding's play The Lion of the West opened at the Park Theater in New York City. James Hackett played the hero: Nimrod Wildfire, a colonel, a congressman, a great hunter, and a "gentleman from the cane." He wore an outrageous animal pelt on his head and made fanciful boasts, repeating many of the things David had said. Crowds immediately made the association, and the play was a huge success for both Hackett and Crockett.

2: THE STAGE

"It is time that the principal events in the history of our country were dramatized, and exhibited at the theatres on such days as are set apart as national festivals."

—Andrew Jackson, quoted in 'The Making of the American Theatre,' by Howard Taubman, published New York: Coward McCann, Inc., 1965, p. 71-72 |

"What a pity it is that these theatres are not contrived that everybody could go; but the fact is, backwoodsman as I am, I have heard some things in them that was a leetle too tough for good women and modest men; and that's a great pity, because there are thousands of scenes of real life that might be exhibited, both for amusement and edification, without offending."

—'An Account of Colonel Crockett's to the North and Down East, in the Year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Thirty Four,' by David Crockett (and William Clark). Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart. 1835 |

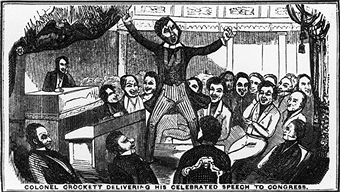

Image from "Scribners" (Collection of the author) |

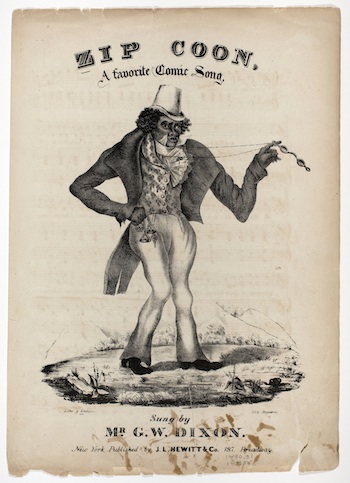

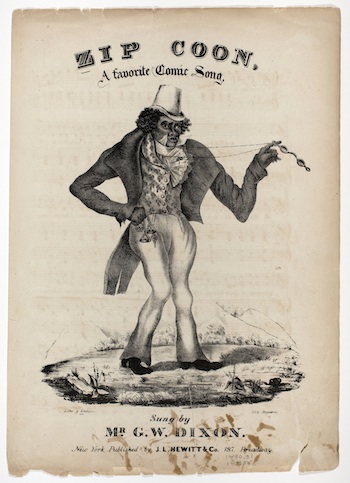

There were various theatrical representations of Crockett while he was in Congress. Songs about Crockett were performed all over the country in concerts and minstrel shows. (See Appendix C.) For instance, J.C. Mossie was touring the theater circuit in a show that featured his impressions of Crockett, Clay, Webster, and Van Buren. In the show, the Crockett monolog was titled, "Crockett's protests against the dandified, the soft talkers, and the effected." (Massachusetts Salem Gazette, May 6, 1834)

Still, the most popular stage characterization based on Crockett during his lifetime was named Nimrod Wildfire, an uncouth Congressman from out of the West. He even drawls when he writes: "I'm half horse, half alligator, a touch of the airth-quake, with a sprinkling of the steamboat! 'If I an't, I wish I may be shot. Heigh! Wake, snakes, June bugs are coming.' Good bye. Yours to the backbone. Nim Wildfire." The character was originated by James Henry Hackett (1800-71), a New York-bred actor and manager. He had studied law and went into business before making his acting debut at the Park Theater in 1826. Hackett was considered the finest Shakespearean comedian of his day, but to most playgoers he was a favorite because of his Yankee characterizations.

On Saturday, November 27, 1830, Hackett announced the winner of a play competition he had created for "an original comedy whereof an American should be the leading character." The prize was $300, and William Cullen Bryant, Fitz-Greene Halleck, James G. Brooks, James Lawson, Prosper M. Wetmore, and William Leggett were the judges. The winner was one of the foremost figures in American literature at the time—James K. Paulding. The bigger winner, however, would be David Crockett. In 1830, Paulding asked well-traveled painter John Wesley Jarvis to supply "a few sketches, short stories & incidents, of Kentucky or Tennessee manners, and especially some of their peculiar phrases & comparisons... If you can, add or invent a few ludicrous Scenes of Col. Crockett at Washington." (Crockett was then serving his second term in the House of Representatives.) Paulding used them to invent the character of Colonel Nimrod Wildfire of Kentucky, a harsh-talking Congressman, "half horse, half alligator."

Two days after the announcement, the New York Courier and Enquirer said Paulding hoped the play "might come to be relished by an American audience, and at length become the vehicle of national character and national feeling," and that the hero was "a member of Congress from Kentucky, full of amusing eccentricity of character and peculiarity of expression."

Everybody knew who the hero was based on: He was then serving his second term in the House of Representatives. Word in newspapers of the work, and word of mouth from the public, immediately connected the character to Crockett. Not wanting to offend, Paulding sent Crockett a message on December 15, 1830, through Congressman Richard Henry Wilde of Georgia: "You will also I hope do me the favour to assure him, provided your knowledge of me will justify the assurance, that I am incapable of committing such an outrage on the feelings of any Gentleman." Crockett wrote back, assuring him no offense was taken, thanking him for his "civility in assuring me that you had no reference to my peculiarities." Crockett biographer James Shackford speculated "a literary hoax which may have been an essential part of the whole wig campaign to make David a more powerful anti-Jackson weapon in the hands of the friends of the U.S. Bank."

Paulding started a campaign of his own, as well. The New York Mirror reported the week before the opening: "The prize play, the 'Lion of the West,' will, we understand, be brought out on Monday evening next, for the benefit of Mr. Hackett. The manner in which this piece has been announced in some of the newspapers, with the most friendly intentions certainly, is, we think, calculated to excite expectations which will not be realized. It may, therefore, be proper to state, in justice to the author, and we do so at his request, that it does not aspire to the rank of a regular comedy. It was written with the desire to introduce Mr. Hackett to the public in a new character, and to aid in producing a taste for dramatic performances, founded on domestic incidents and native manners. The author had no idea of becoming a candidate for the prize offered by Mr. Hackett, but circumstances induced him to consent that it should take that course. Another error has likewise been propogated through the same medium. It has been stated that the principal part was designed to represent a member of congress, somewhat noted for his eccentricities. The author disclaims such an intention." (4, p. 335)

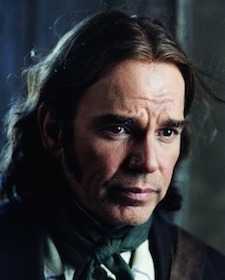

James Kirke Paulding (Collection of the author) |

Paulding used stories like this to invent the character of Colonel Nimrod Wildfire of Kentucky, a harsh-talking Congressman, "half horse, half alligator." Brash, cocksure and adventurous, he symbolized the ever-expanding West. Crockett had risen to a position of true power in government that had never been possible for someone from his station before, using that very character—and Crockett's influence made the character even funnier. This was a new, very American phenomenon in which a poor Tennessee farmer could promote himself to a level in society previously reserved for the very wealthy or through supposed divine right... it was a naturally funny, fish-out-of-water situation, and it was real, damn it!

But not everybody was in on the joke. French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville visited the country in 1831 to research his book De la Démocratie en Amerique (1835). After meeting Crockett, he pondered the problem with letting the lower classes vote: "Two years ago the inhabitants of the district of which Memphis is the capital sent to the House of Representatives in Congress an individual named David Crockett, who had received no formal education, could read only with difficulty, had no property, no fixed dwelling, but spent his time hunting, selling his game for a living, and spending his whole life in the woods."

The play was the first American-made blockbuster, with Hackett averaging a nightly box-office take of $900 during November of 1831. However, while the character of Wildfire was a hit, the play was not satisfying to Hackett and Paulding, so it was immediately withdrawn for revisions, which Paulding allowed John Augustus Stone to write. Stone retained only the basic plot and the character of the Congressman, and then added a reserved British woman named Albina Towertop for contrast to Wildfire. Hackett then took The Lion of the West on a national tour throughout 1831 and 1832. Afterwards, new material by Paulding was incorporated after a series of newspaper columns he had written in July and August for the New York Mirror, in which he satirized Mrs. Frances Trollope, British author of a travel book entitled Domestic Manners of the Americans.³ The articles told of an imagined meeting between her and Wildfire, "one of the most decidedly celebrated and popular men in America." The character of Albina Towertop was then changed to Mrs. Amelia Wollope from England, whom has come to New York to "ameliorate the manners of the Americans."

In the new story, Wildfire hears that she's in New York and offers to visit. He is told to send up a card, and he sends up a king of clubs. Finally, they meet:

MRS. WOLLOPE: May I offer you a cup of tea?

WILDFIRE: Much objected to you, madam. I never raise the steam with hot water—always go on the high pressure principle — all whisky.

MRS. WOLLOPE: A man of spirit! Are you stationed in New York, sir?

WILDFIRE: Stationed—yes! But don't mean to stop long. Old Kaintuck's the spot. There the world's made upon a large scale.

MRS. WOLLOPE: A region of superior cultivation—in what branch of science do its gentlemen excel?

WILDFIRE: Why, madam, of all the fellers either side of the Alleghany hills, I myself can jump higher-squat lower-dive deeper-stay longer under and come out drier.

MRS. WOLLOPE: Here's amelioration! And your ladies, sir?

WILDFIRE: The galls! Oh, they go it on the big figure too-no mistake in them. There's my late sweetheart, Patty Snaggs. At nine year old she shot a bear, and now she can whip her weight in wild cats. There's the skin of one of 'em. [Takes off his cap.]

Hackett then took the show to Covent Garden in London, and he had it rewritten by William Bayle Bernard, cutting it down from three acts to two. It was re-titled The Kentuckian, or a Trip to New York, and the character of Mrs. Wollope was changed to "Mrs. Luminary," as not to offend British audiences. Completely rewritten twice, the only constant in the play was the character of Colonel Nimrod Wildfire.

Enter servant, with letter.

SERVANT

A letter, Mr. Freeman.

FREEMAN

Ha, from my nephew, Colonel Wildfire.

MRS. FREEMAN

Indeed!

FREEMAN

It is dated Washington, and he is now on the road to New York to spend the summer with us.

MRS. FREEMAN

I regret to hear it.

FREEMAN

Regret!

MRS. FREEMAN

Unless he has corrected that barbarity of which I have heard such descriptions.

FREEMAN

Come, come—consider the circumstances of his education. My sister emigrated to the heart of the Backwoods when they were much less settled than at present. This Nimrod was born a thousand miles from good society, and if his manners are abrupt, they convey a native humour which I think highly entertaining. Listen to this letter.

(Reads.)

"Uncle Peter—Washington, July 1st. Here I am, only two day's journey from New York! The very day I got your coaxing letter I packed up my shirts and some other plunder and set right off a horse-back under high steam. On my way I took a squint at my wild lands along by the Big Muddy and Little Muddy to Bear Grass Creek, and had what I call a rael roundabout catawumpus, clean through the deestrict. If I hadn't I wish I may be te-to-taciously ex-flunctified."

MRS. FREEMAN

There, Mr. Freeman, what do you term that?

FREEMAN

The veritable Kentucky vocabulary. Stay—hear the conclusion.

(Reads.)

"But, Uncle, don't forget to tell Aunt Polly that I'm a full team going it on the big figure! And let all the fellers in New York know—I'm half horse, half alligator, a touch of the airth-quake, with a sprinkling of the steamboat! 'If I an't, I wish I may be shot. Heigh! Wake, snakes, June bugs are coming.' Good bye. Yours to the backbone. Nim Wildfire."

Despite their assurances to each other that no connection should be inferred between Wildfire and Crockett, both David and Hackett obviously loved the attention the association brought. Shackford wrote that the play "tremendously nationalized and pictorialized the name reputation of David Crockett, and precipitated about his name much of the current tall-tale legend of the West."

By 1832, David's fame was growing wildly... even though he was not taking part in it. Around this time, Matthew St. Clair Clarke, a rich eastern Whig who worked as the Clerk of the House of Representatives, visited Crockett at his home in Weakly County, Tennessee. Clarke reportedly found Crockett living alone, deeply in debt, sleeping on the earthen floor of his cabin in animal skins, and eating meals of bear meat with a Bowie knife and cane fork. Clarke informed Crockett that the Whig Party was looking at him as their answer to Democratic President Andrew Jackson — as the true representative of the "common man" — and that the party was interested in backing Crockett as their candidate in the next Congressional election.

To energize David's campaign, they agreed to publish a book of his exploits (and possibly to pay back some of the Whigs that have been loaning David money). St. Claire Clarke returned home and either wrote or commissioned (depending on whose account you believe) The Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee, by "Anonymous." The book was later re-titled Sketches and Eccentricities of Colonel David Crockett, and its authorship was attributed to Whig writer James Strange French. When the biography was re-published by a larger company out of New York it became immensely popular, although David received no royalties from the sales. It is part biography and part humor book, with several chapters being folk tales written in a thick Dutch accent (which is a popular form of storytelling at this time on the frontier). David now became the second most famous man in the country — after Andrew Jackson. But David's fame wasn't based on war heroics or political achievement — it was based on his personality. He became the first man in American history to be famous just for being famous — the first "celebrity."

STAGE VERSION: "I'm half horse, half alligator, a touch of the airth-quake, with a sprinklin' of the steamboat! 'If I an't I wish I may be shot! Heigh! Wake snakes, June bugs are coming.'"

—"The Lion of the West" (1831) |

BOOK VERSION: "I am that same David Crockett, fresh from the backwoods, half-horse, half-alligator, a little touched with the snapping turtle; can wade the Mississippi, leap the Ohio, ride upon a streak of lightning, and slip without a scratch down a honey locust; can whip my weight in wild cats, --and if any gentleman pleases, for a ten dollar bill, he may throw in a panther,--hug a bear too close for comfort, and eat any man opposed to Jackson."

—"The Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee" (1833) |

Strangely enough, David's notoriety was growing so quickly that it began to fold in on itself: In creating dialogue for David in the book, the writer incorporated dialogue from The Lion of the West (which had, in turn, incorporated dialogue from David's speeches). Suddenly the real David and legendary Davy are stealing from each other, several times over.

Crockett was supposedly outraged by the caricature that the book presented of him, but found once again that it made him even more popular. Thanks to the media blitz of books and plays, he was now one of the best known men in the United States. The Whigs then backed him for reelection. Whig leader Nicholas Biddle, who ran the United States Bank, even loaned David money, then struck the debt from his accounts.

"I have seen a great man. No less of one than Col. Crockett. I . . . sat close by him so I had a good opportunity of observing his physiognomy. . . . He is wholly different from what I thought him. Tall in stature and large in frame, but quite thin, with black hair combed straight over the forehead, parted from the middle and his shirt collar turned negligently back over his coat. He has rather an indolent and careless appearance and looks not like a 'go ahead' man."

—Seventeen-year-old Helen Chapman to her mother in 1834, in a letter which she tells of seeing David Crockett in New York City. |

Chapman's portrait of Crockett |

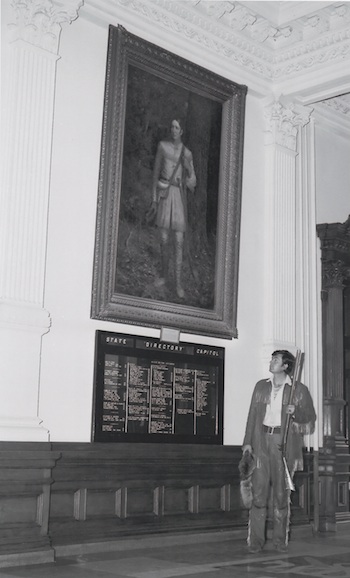

In 1833, David ran again for the Twenty-third Congress, and won. Now he played to his legend completely, posing for several portraits, but complained they made him look like "a sort of cross between a clean-shirted Member of Congress and a Methodist Preacher." In an attempt to create a painting that is more in line with his image, David posed for a full-length portrait with hunting dogs (he wanted mutts that looked like their tails had been bitten off by bears), a linsey-woolsey hunting shirt, broad rounded hat (no coon-skin), leggings and moccasins — none of which he personally had, and rounded up from all around Washington. Painter John Gadsby Chapman attempted to write David's name on his hunting knife as an engraving, but could only fit in enough letters to spell "Crocket." David approved of the spelling, saying the second 't' was totally unnecessary.

Chapman wrote that Crockett "rarely, if ever, exhibited either in conversation or manner, attributes of coarseness of character that prevailing popular opinion very unjustly assigned to him." One day they met on Pennsylvania Avenue, as Crockett was coming out of a long congressional debate, looking "very much fagged." Chapman said, "You look tired, Colonel, as if you had just gone through a long speech in the House." Crockett answered, "Long speech to thunder ... there's plenty of 'em up there for that sort of nonsense, without my making a fool of myself, at public expense. I can stand good nonsense — rather like it — but such nonsense as they are digging up yonder, it's no use trying to — I'm going home."

Finally, Hackett brought the show to the nation's capital in 1833, when Hackett played Wildfire scenes from the play in a command performance for the Washington elite, with David Crockett himself in attendance:

The New York 'Spirit of Times', reported on 21 December 1833:

| "The Washington Correspondent of the Patriot, says: "Col. Crockett made a prodigious figure last night at the Theatre. Hackett was to play Nimrod Wildfire — and Col. Crockett attended by invitation. A whole box was assigned the Colonel, —and the Col. bowed and Nimrod Wildfire bowed, both at each for a long time, as if old acquaintances, —while the Theatre rung with the cheers of the multitude assembled." |

Francis Hodge's Biography of a Lost Play, 'Lion of the West', noted that "the line between the man in public life and the nineteenth-century actor was not clearly discernible, and as far as the public was concerned the actor frequently took second place in the continuing competition between the platform and the stage."

During his tour of the Eastern states in 1834, Crockett also visited theatres in New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia that had featured the play, and he began to feel exploited. In New York in 1834, "I found a bill for the Bowery Theatre; and it stated I was to be there. Now I knew I had never given the manager any authority to use my name, and I determined not to go. After some time, I was sent for, and refused; and then the head manager came himself. I told him I did not come for a show; I did not come for the citizens of New York to look at, I come to look at them. However, my friends said it would be a great disappointment, and might harm the managers; so I went, and was friendly received. I remained a short time, and returned. So ended the first day of May, 1834." The theatre was featuring a play at that time about Major Jack Downing, "a sort of Yankee Davy Crockett," and Crockett's name was likely placed on the bill by the Whig politicians who were promoting his East Coast tour through April and May, and the managers knew his "real life" appearance would be publicized more than any stage actor portraying a folk hero.

The character of Wildfire was such a success that Laurence Hutton wrote, "many contemporary imitators, who copied his dress, his speech and his gait and stalked through the deep-tangled wildwoods of East Side stages for many years, to the delight of city-bred pits and galleries." But none of those characters could match Nimrod Wildfire.

During 1834, in an effort to correct the image of him presented in both the play and in Sketches and Eccentricities of Colonel David Crockett (and after seeing how much that book was making while he received no royalties), David worked with fellow Congressman Thomas Chilton on a new book, part life-story, part campaign literature, entitled A Narrative in the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. Why did Crockett need a co-writer? The following correspondence should tell you — it's a letter David sent to publishers Carey and Hart on February 23rd:

| "Gentlemen: For Some days I have been anxiously expecting the arivel of a Copy of my book which you had the goodness to promis to Send me So Soon it was finished. But as you were mistaken in its length when you Stipulated the time at which I would receive a Copy I Suppose its completion has been probably delayed by that Circumstance I desire it early as may Suit your Convenience." |

But illiteracy has never been much of a stumbling block in national politics. David was given a tour of the East and New England, where huge crowds greeted him. (Before leaving, he met with former Tennessee Governor Sam Houston, who has just returned from years in seclusion living with the Cherokee. Sam was hoping to obtain a grant to sell land in Texas, a province of Mexico, and told David of the huge tracts of game-filled land, available for very little money. David was intrigued, and began writing of Texas more and more in his correspondence.

But Texas is a long way off—David is placing himself in position to run for President of the United States, touring the Eastern states. David is showered with gifts and praise, and is starting to believe his own press. He wears a fashionable wool overcoat presented to him by a Boston manufacturer. Philadelphia presents him with a beautiful rifle he names "Pretty Betsey." and two more books quickly follow—an account of his tour of the Eastern states and a biography of Martin Van Buren), but both are ghost-written by other authors, with Crockett supplying notes. David enjoyed his notoriety and began to dress and act like a cultured, refined man—which is, of course, just what the public didn't want. They wanted "Davy"—and if David wouldn't give them that, there were plenty of hack writers who would.

Davy Crockett almanacs started appearing—entirely devoted to tall tales of him. Readers were told they were printed in Nashville, under his authorship, but in fact were created back East, and David has no control over them, or their content. The early editions just copied tales from his books, but soon the real writers were creating newer, more outrageous adventures that had nothing to do with the real man. The language grew cruder and less literate. The Davy of the almanacs crowed: "It isn't every member of Congress that knows how to authorise as well as to speechify. And it remains to be larnt whether I shall go down to posteriors with most credit as a Congressman or a writer." (1836 Almanac, page 2). As a result, David became the butt of the joke as often as he was the hero. He waded the Mississippi in stilts to keep his feet dry and his whiskey undiluted; he was caught naked while sleeping with the wife of a stage driver, and had to subdue the husband with a fireplace poker, thrusting it down his throat. The stage driver was so impressed by David's fighting prowess that he promised to vote for him in the next election. To help the realism, Davy adds: "This adventure I never told to Mrs. Crockett" (1836 Almanac, pages 33-34).

David's legend was now growing apart from him, and even beyond him. He began to grow tired of meeting people who were shocked, quote, "at finding me in human shape, and with the countenance, appearance, and common feelings of a human being." But he could do little to stop it: When Halley's comet appeared; it was said that his political nemesis, President Andrew Jackson, has commissioned him to climb the Alleghenies and wring its tail off in order to snap a cold spell:

"One winter, it was so cold that the dawn froze solid. The sun got caught between two ice blocks, and the earth iced up so much that it couldn't turn. The first rays of sunlight froze halfway over the mountain tops. They looked like yellow icicles dripping towards the ground. Now Davy Crockett was headed home after a successful night hunting when the dawn froze up so solid. Being a smart man, he knew he had to do something quick or the earth was a goner. He had a freshly killed bear on his back, so he whipped it off, climbed right up on those rays of sunlight and began beating the hot bear carcass against the ice blocks which were squashing the sun. Soon a gush of hot oil burst out of the bear and it melted the ice. Davy gave the sun a good hard kick to get it started, and the sun's heat unfroze the earth and started it spinning again. So Davy lit his pipe on the sun, shouldered the bear, slid himself down the sun rays before they melted and took a bit of sunrise home in his pocket."

—Folktale re-told by S. E. Schlosser |

In real life, Crockett said he'd rather wring Jackson's tail than Halley's, and then "authored" another book—this time a mock biography, trumpeting Jackson's protégé, the bald Martin Van Buren, as "hair-apparent" to the presidency. In response, Jackson killed off David's land bill one last time, hoping to finally rid the Congress of "Crockett and company." The Jacksonians conspired to make sure that David can't get a single bill on the floor of the House. They use David's new image to ridicule him, calling him "the Western David," and "David of the River" (shades of "gentleman from the cane"). David's Whig friends didn't help, either — their policy was not to give away public lands in small tracts to the poor, but to give it away in large tracts to themselves. They also concluded that Crockett was too unpredictable to make a useful president, and let him flounder alone.

Despite being a legend in his own time, the real David was now fighting for his political life. He ran for reelection against Adam Huntsman, a one-legged man due to a wound he received during the Indian wars. Huntsman calls David's Congressional record sorry—for six years he's sat in Congress, accomplishing nothing. In three terms, he's failed to get a single bill passed. David's land bill has fallen again with a loud thud. Huntsman points out that Crockett's tour of the East to promote his autobiography took place over three weeks at the height of the Congressional session, when David should have been working. He also accuses David of neglecting duties, womanizing, and being a drunk.

David was eventually defeated by "the timber-toe" in his bid for reelection. As far away as Arkansas, the Jackson press celebrates Huntsman's victory over "the buffoon, Davy Crockett." David discovers too late that being a ring-tailed roarer makes him nationally known, but it doesn't make him a successful Congressman. The American people want Davy Crockett exploring the wilderness, not spewing useless Anti-Jackson rhetoric on the floor of the House and watching Bills die in Congress. And David's not that excited about it anymore, either.

Politics had finally succeeded where poverty, malaria, and Indian wars could not—the "Go Ahead" man finally gave up. David stated he was tired of the constant campaigning, the arguing, the partisanship, and most of all, the compromise. He was even tired of Tennessee. He decided to start over yet again. He headed off for a fresh start in a new country—the unspoiled paradise in Mexico that Sam Houston told him about in 1834: Texas.

"My friends, I suppose you all are aware that I was recently a candidate for Congress. I told the voters that if they would elect me I would serve them to the best of my ability; but if they did not, they might go to hell, and I would go to Texas. I am on my way now!"

—David Crockett to former constituents at McCool's Saloon, 1835 |

The Lion of the West and its various incarnations outlived Crockett himself, who was brutally killed on a cold March morning in 1836. Nimrod Wildfire was still bragging, flag-waving and entertaining while David was left to die outside of the United States, out of bullets, and out of brag. Still, there were reports of Crockett surviving the battle and being held prisoner while working in Mexican mines appearing every so often in newspapers. Eldest son John Wesley Crockett even had one of the reports investigated, but it proved to be untrue. (The rumor would go on to inspire at least three film projects in the 1980s and 1990s. Much like the resurrected Crockett, the films never materialized.)

Hackett toured with The Lion of the West for decades after Crockett's death. It played in England, Ireland, and all over the United States. It was in Chicago as late as 1858. It became the most-often performed play on the American stage until Uncle Tom's Cabin.

But 200 years later, the only surviving document of this Southwestern frontier archetype was actually written by a British playwright. Now that's funny...

"Although Crockett was once an actual entity he is now no more than the immaterial excuse for an infinity of legend."

—"Scribner's Monthly," Vol. XVIII, No. 3; July, 1879. "The American On The Stage," by J. Brander Matthews |

"Melodrama exalted the traditional values to which people clung in the face of fundamental change, audiences credited melodrama with being more real than reality, a higher truth that transcended everyday experience. An ideal statement of the way life ought to be, melodrama made evil and corruption easy to identify and solutions easy to find; it made heroes of common, simple people; and it made virtue and the virtuous triumph."

—Robert Toll, "On with the Show! The first century of Show Business in America" (p. 147) |

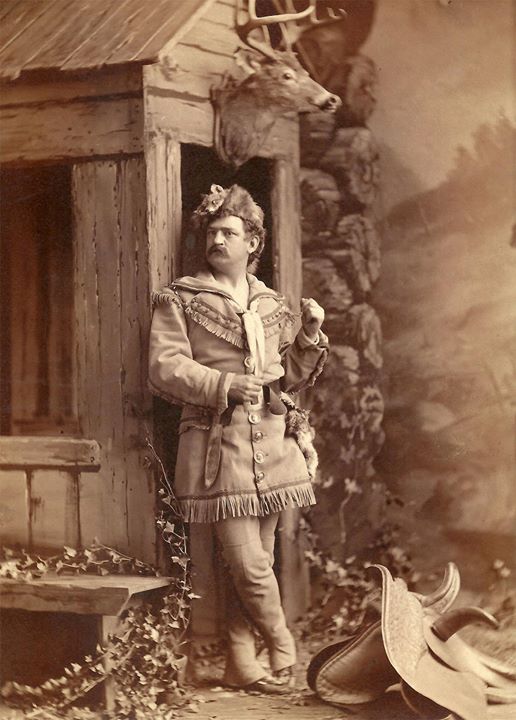

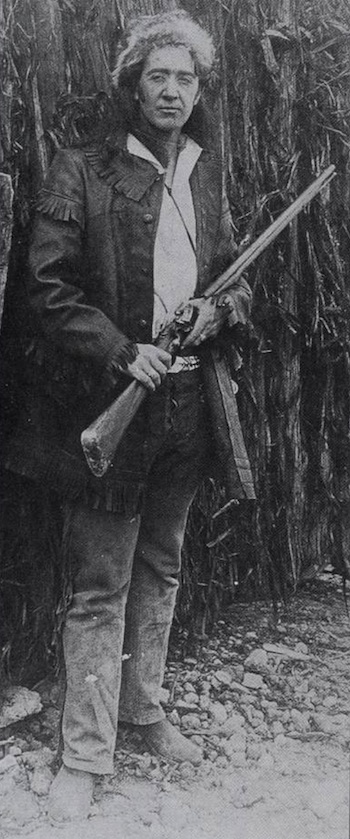

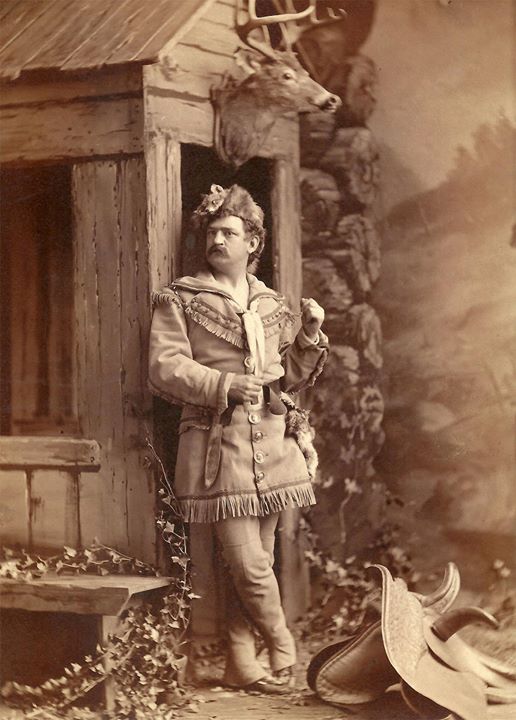

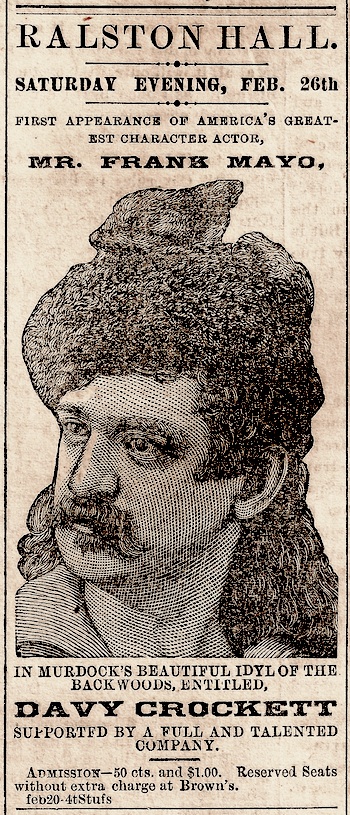

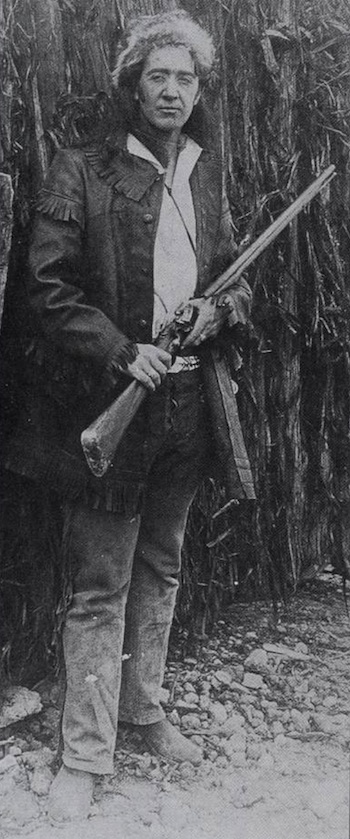

Cabinet photo of Mayo in costume. Collection of the author |

After Crockett's death, his political clout was felt everywhere: In 1840, the Whigs' presidential candidate William Henry Harrison won the presidential election with a "log cabin and hard cider" campaign, wearing a fur cap and pretending to be a frontiersman. The Whigs pushed him as a man of the people and "backwoods democracy," ala their former hero, Crockett. He even became the first presidential candidate to make stump speeches around the country, ala David... But he was no Crockett — after riding into Washington on a white stallion, he caught pneumonia and died. The Whigs died soon after, folding into the Republican Party.

In 1841, David's son, John Wesley, was elected to Congress. Calling on the memory of his father, John Wesley finally passed the long-stifled land bill, completing David's dream. (It became what is now known as the Homestead Act.) John Wesley told Congress: "You have doubtless seen the account of my father's fall at the Alamo in Texas. He is gone from among us, and is no more to be seen in the walks of men, but in his death like Sampson, he slew more of his enemies than in all of his life. Even his most bitter enemies here, I believe, have buried all animosity, and joined the general lamentation over his untimely end."

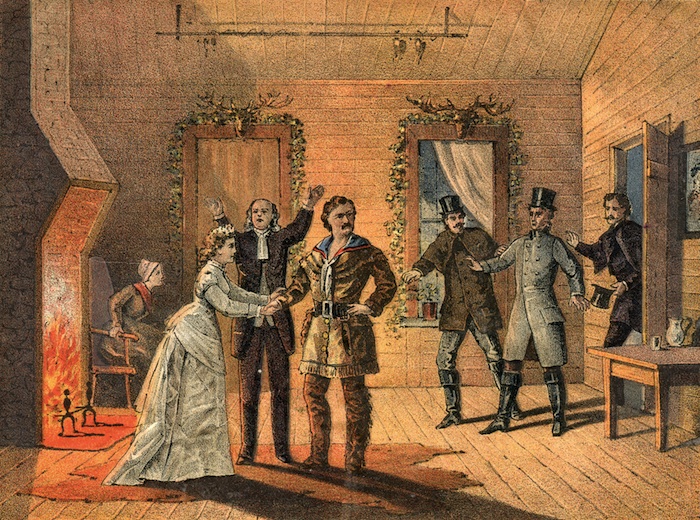

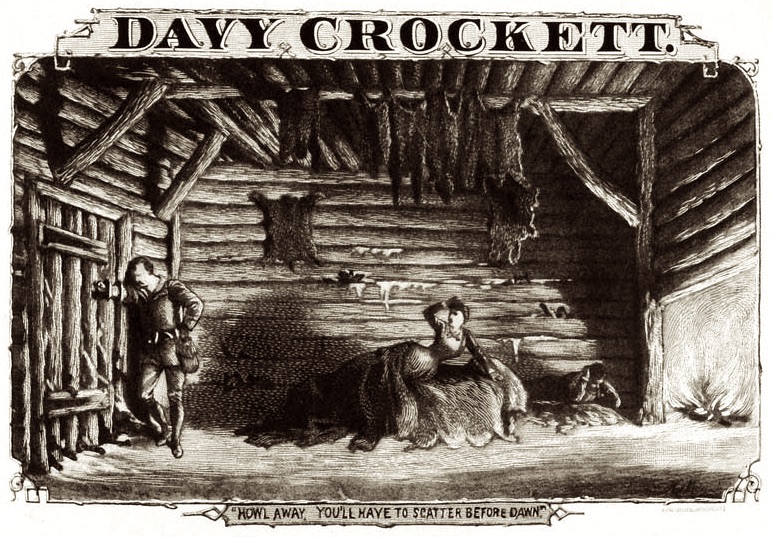

As the 19th century progressed, the wild frontier became more of a memory than a reality. Farms replaced forests, towns replaced settlements, trains replaced wagon trains, and bragging, slave-holding Southern backwoodsmen were relaced by surrendered ex-Confederates. The national character known as Davy Crockett had to be tamed just like the wilderness he lived in, and underwent his own Reconstruction. Davy became a cleaned-up version of what was being lost — not a "screamer," a buffoon, or a politician (is there a difference?). Davy became nostalgia, representing a sentimental, even romantic figure. In the most famous play of the period, Davy Crockett, he was portrayed as a noble, romantic backwoodsman who was unlucky in love. This Davy has almost no relation to the real man: He is 25 and still living with his mom (the real Crockett was married and working on his third child); he still hunts — but killing the creatures makes him "shudder." Despite the time frame of the play being before the Civil War, and written just a handful of years after the conflict, there are no slaves in the play, let alone African-Americans. Manifest destiny, wars, slaves, and the brags all disappeared, replaced by a simple cabin in the woods, peaceful homesteaders, and humility that even a mother could love.

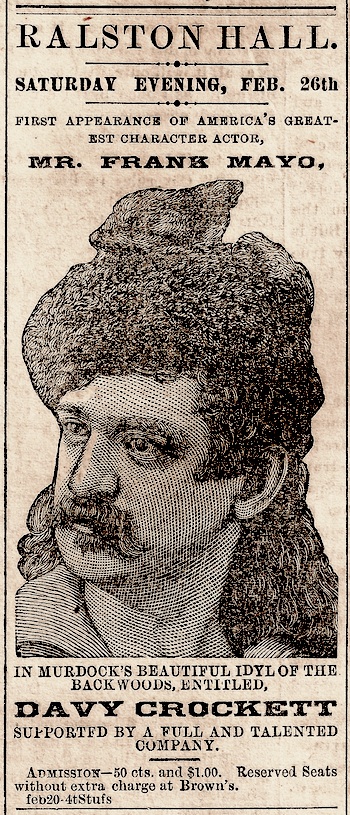

The star of the play, Frank Mayo, was one of the few native-born American actors who rose to fame in the last half of the nineteenth century. Born on Essex Street in Boston on April 18, 1839 with the birth name of Frank Maguire, he came out to California during the Gold rush, then ended up in the theater. Mayo made his speaking debut at the age of 17, as a waiter in Raising the Wind at the American Theater in San Francisco. Mayo had been employed in various minor capacities at Maguire's Opera House (peddling peanuts, captain of the supers, and the like) when he became star struck. He headed for New York in July of 1865.

Author Frank Hitchcock Murdoch crafted the play from the outset as a nostalgic look back at a frontier that had started disappearing fifty years before. In opposition to the Buffalo Bill-style westerns of the day, and completely different than the farce Lion of the West, this play was a romantic melodrama in a lush, romantic wilderness. Unfortunately he didn't live to see its success. Scribners reported that, "The author of the 'Davy Crockett,' Mr. Frank Hitchcock, had taken the pen-name of Murdoch, borrowing it from his maternal uncle, Mr. James E. Murdoch, the Shakespearian reader and actor. He had written other plays, one of which, called Bohemia, was brought out at the Arch Street Theatre, in Philadelphia, and was so hardly handled by the critics that the author lost faith and hope and died at the early age of thirty." After the disastrous run of Bohemia in Philadelphia, Murdoch wrote to Mayo of the reviews and said, "they have struck home." Within two days, he was dead from "brain fever." So Murdoch never even saw the premiere of Davy Crockett... but J. Brander Matthews wrote in Scribner's, "Perhaps it is well that he did not,—for the play failed dismally when first acted. But the actor had more healthy obstinancy ; he believed firmly in the piece, and he soon found the public beginning to appreciate it."

Davy Crockett was first produced in Rochester, New York, where Mayo was the manager. He played the role of Davy for the first time on September 15, 1872. Mayo had faith in the piece and kept rewriting it himself. He designed it to attract a female audience as much as the male. In his book, Performing the American Frontier, 1870-1906, Roger A. Hall writes the play "was constructed from its inception with romantic, poetic, and artistic aspirations, looking back to a hero whose time had already passed."

The sentiment of those lost good ol' days on the frontier are really driven home by Davy's entrance: after hearing his voice offstage, "as clear as a bell and as sharp as the crack of a rifle," says his friend, Yonk—the song Auld Lang Syne swells in the background as we see Davy himself in buckskins, 25 years old (according to the opening night program), carrying a two-year-old buck over his shoulder — his 42nd of the season, although killing the creatures makes him "shudder." His mother, Dame Crockett, informs him that his childhood sweetheart, Little Nell, has come back from a long stay abroad with her now-deceased father. Little Nell now calls herself by her proper name, Eleanor Vaughn, and she brings with her, her uncle and guardian Major Hector Royston, and her fiancé, Neil Crampton. Davy, of course, distrusts them immediately. He resolves to follow them and see what they're up to, proclaiming his motto, "Be sure you're right, then go ahead!"

They are headed for the estate of Neil's uncle, Oscar Crampton. Davy is quick to sense something is wrong. He decides to run ahead and offer the party the shelter of his hunting hut, since it has started to snow. The decision proves wise, for Neil has been hurt and his blood has attracted wolves. Davy helps them inside the cabin — he has to carry Eleanor, "fainted and freezing," then while Neil sleeps off a fever, Davy warms the cabin by burning the wooden log used for barring the door in the fireplace, and Eleanor reads him Sir Walter Scott's poem of Lochinvar. The scene goes like this:

Front-page ad from the Macon Ralston Hall Theater in the "The Macon Telegraph and Messenger" newspaper, dated February 22, 1876. Collection of the author. |

ELEANOR

How good you are, Mr. Crockett!

DAVY

Don't say that, miss, for what I did for you I'd have did for any living soul that came to my door in a storm like that. But you are safe, and I thank the eternal for that.

ELEANOR

How strange we meet again!

DAVY

Yes, 'tis kind of singular.

ELEANOR

Is this your hunting lodge?

DAVY

Yes, this is my crib. This is where I come and bunk when I'm out on a long stretch arter game. Miss, here's something that belongs to you—

(hands her book)

You left it at my mother's house—

ELEANOR

Oh, Marmion!—it's dear Sir Walter's book.

DAVY

Is it? I allowed it was yours.

ELEANOR

Yes—I mean—thank you very much.

DAVY

Oh, you're right welcome—what is that, sermons?—No?—Law, maybe—No? Well I guess I allowed it was, 'cause that's what your lawyer and parson needs.

ELEANOR

Yes, and very good reading it must be. But this is lighter.

DAVY

Is it? Yes, that's right, light—I've seen weightier books than that.

After reading the poem, they discover that they have been tracked to the cabin by a hungry, menacing foe:

DAVY

That's wolves.

ELEANOR

Wolves—!

(Screams)

DAVY

Don't be skeered.

ELEANOR

But—is there no danger?

DAVY

Ain't I here?

ELEANOR

Yes, but they are so dreadfully near.

DAVY

Yes, they tracked you in the snow, and smell blood.

ELEANOR

Blood!

DAVY

Take it easy, girl. This door is built of oak. I built it—and—blazes, the bar's gone!

(Warning curtain)

ELEANOR

Gone!

(Wolves howl all around cabin)

DAVY

Yes, I split it up to warm you and your friend. Rouse him up. The pesky devils is all around the house.

ELEANOR

(Goes to Neil)

Neil—help!

(Wolves throw themselves gainst door. Bark)

DAVY

Quick, there. I can't hold the door agin 'em—

NEIL

I tell you, Uncle, if the girl says no, there's an end of it—

ELEANOR

My God—he is delirious!

DAVY

What!

ELEANOR

'Tis true, nothing can save us!

DAVY

Yes, it can!

ELEANOR

What?

DAVY

The strong arm of a backwoodsman.

(Davy bars door with his arm. The wolves attack the house. Heads seen opening in the hut and under the door)

TABLEAU

The Third Act begins right where the Second Act ended: Crockett is still bolting the door with his arm as Eleanor sleeps, and he utters the immortal, hilrious line: "This is getting kind of monotonous, this business is."

The group is saved, and when the party finally reaches old Crampton's estate, the uncle is revealed as a villain who is blackmailing Royston with forged papers and forcing his nephew to marry. Davy, like young Lochinvar, arrives to rescue his sweetheart. He takes her home and marries her, then destroys the uncle's papers while she gives the old man her inheritance in order to settle his debts.

Critics were as ecstatic as the audiences: The New York Herald critic said on March 10, 1874: "Mr. Frank Mayo as Davy Crockett plays with care and a fidelity to sense that captivates. He allows nothing to tempt him into rant. He is the nearest approach to true American comedy acting that has been yet seen.” The New York Spirit of the Times (August 30, 1879) said, Mayo "gave us a fresh, breezy picture of a new life, and was by turns friendless and vigorous, humorous and tender, always truthful." On March 23, 1875, the New York Herald called the play, "immeasurably the best of the American dramas."

On March 1, 1878, Alamo survivor Susannah Dickinson (then named Hannig, being remarried to a local cabinet maker) attended a performance of the play at Austin Opera House in Texas. Almost exactly 42 years before, she had stared down at Crockett's mutilated corpse in the Alamo, expecting a similar fate for herself. What thoughts must have gone through her head? Did Mayo's character seem related at all to the man she knew? Did she think, "That's funny, Mr. Crockett never mentioned Eleanor, Sal, Yonk, or Omnes?" Was she pleased by the fiction of it, or angry? We'll never know, because she didn't tell anybody what she thought of the play. If it did bother her, she probably felt that she had experienced enough conflict around the Alamo, already, and let the matter drop.

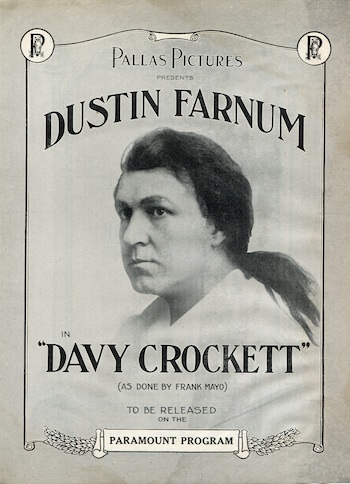

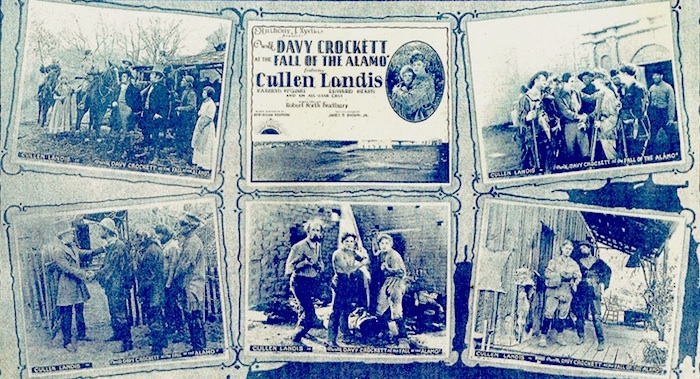

Mayo continued to tour with the play until his death in 1896, having performed the part over 2000 times-including a performance two days before his death. Mayo left behind a wife and three children-including son Edwin, who continued to perform as Crockett after his father's death. The play served as a beloved reminder of the frontier for decades, playing on stage and silent screen, culminating in a big-budget (for the time) film in 1916 that was written by Edwin's son, who inherited both his grandfather's name, Frank, and his profession as well.

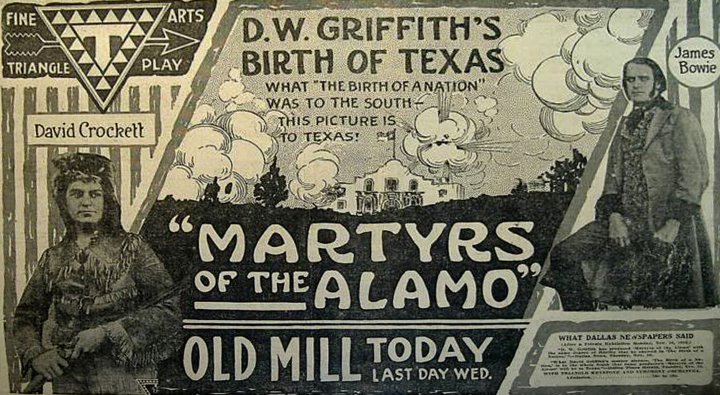

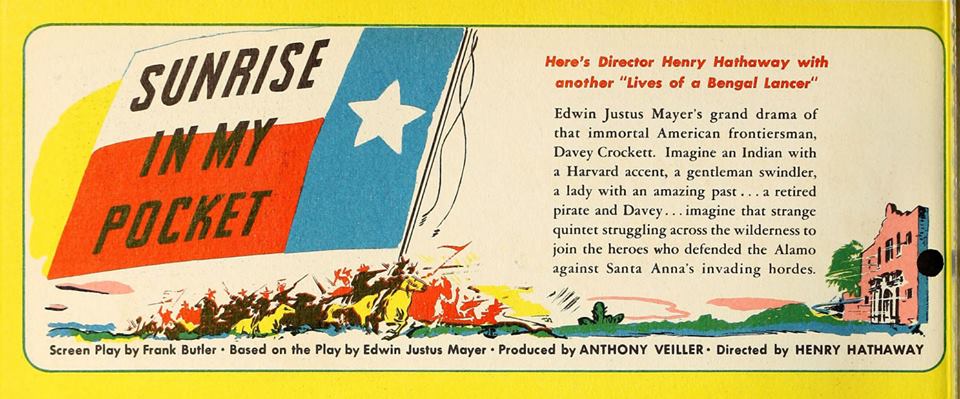

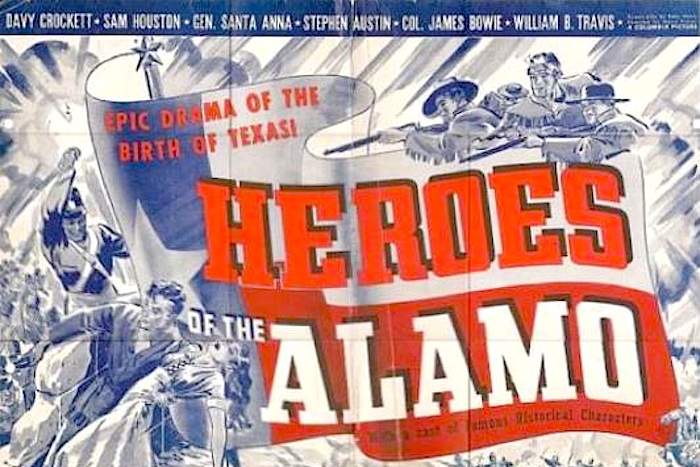

3: THE SCREEN. The End of the Frontier; Mexican-American War

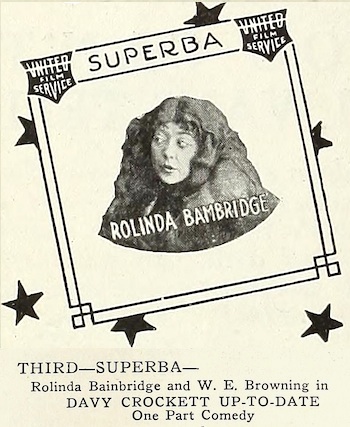

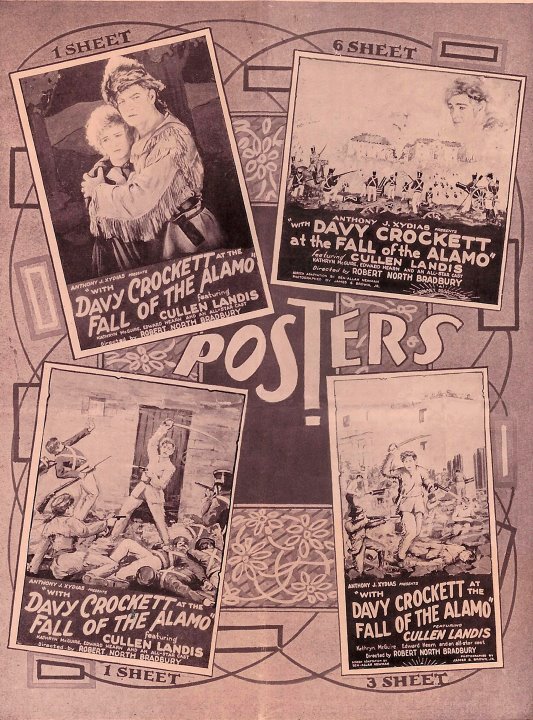

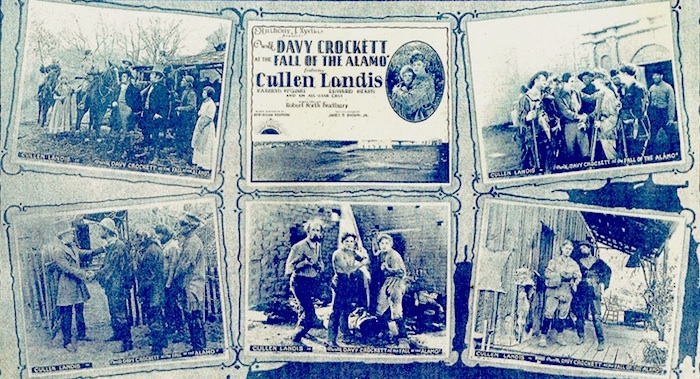

What is a politician without a voice? Davy Crockett was the subject of many silent films, but his personality was muted: A good Crockett brag would never fit onto a single title card in a silent movie! So his character had to be refitted as a strong, silent type and he was relegated to action films or simplified retellings of Mayo's melodrama.

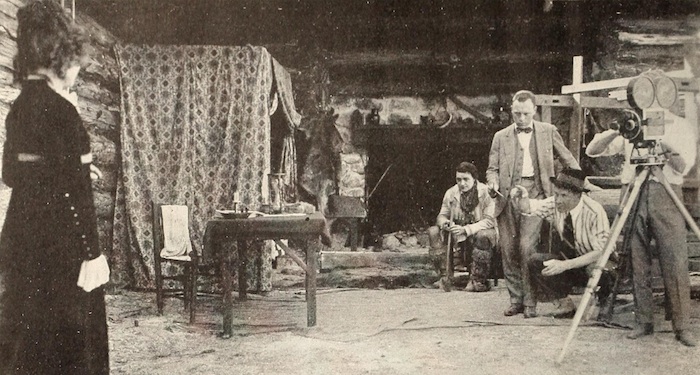

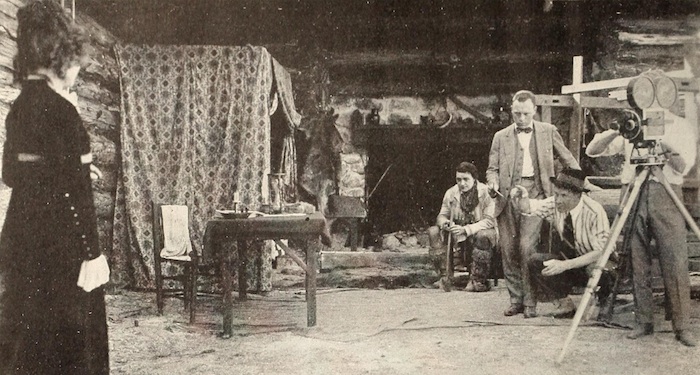

Unfortunately, our knowledge of these films comes mostly from contemporary trade magazines and newspapers, as the majority of them are now considered lost. Only a fraction of the American films created during the first four decades of the motion picture still survive in the United States—probably fewer than 20 percent. There are many reasons for this: Films were made quickly, sent into distribution channels and mostly forgotten soon after their first runs. Due to the high cost of film, and the fact that one print could be shown to thousands of people, films prints were produced in small quantities, and prints were often destroyed when they had worn out. Surviving prints were stored haphazardly, if at all. Archiving films was too expensive, so prints were destroyed to save on storage costs. Then with the advent of the talkie era, silent films were considered worthless, and many of the companies that distributed them went out of business. Even for the studios that survived, a silent film's potential as long term sources of revenue was unknown to early movie industry executives. So many films were deliberately destroyed. The importance of archiving silent films wasn't realized until after it was too late, and many classic films were lost forever.

Furthermore, it was dangerous storing silent films. Cellulose nitrate film was used for the majority of films—a highly flammable compound, and many prints were lost in fires, as were many projectionists. Even if the film stock didn't burst into flames, it only had a life of between thirty and eighty years. The decomposition of nitrate film is impossible to stop, and the films all eventually melt into sticky cannisters full of goo in storage. Some films were recycled for their silver content or simply thrown away to save space. So unless new prints were made, what we have today for the most part from silent films are posters, stills, reviews... and a lot of guitar picks.

While most early films featuring the character of Davy Crockett no longer survive, we know the first was filmed in 1909. It was the year that Theodore (Don't call him "Teddy") Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, left office after declining to run again. Roosevelt had formed the Boone and Crockett Club, a conservationist organization named in honor of Roosevelt's heroes, Crockett and Daniel Boone, whom the club's founders viewed as ethical hunters and honest men who loved the outdoors and earthly pursuits. Roosevelt had written of Crockett: "He was the most famous rifle-shot in all the United States, and the most successful hunter, so that his skill was a proverb all along the boarder." [Stories of the Great West, by Theodore Roosevelt. The Century co (1909). p.99]

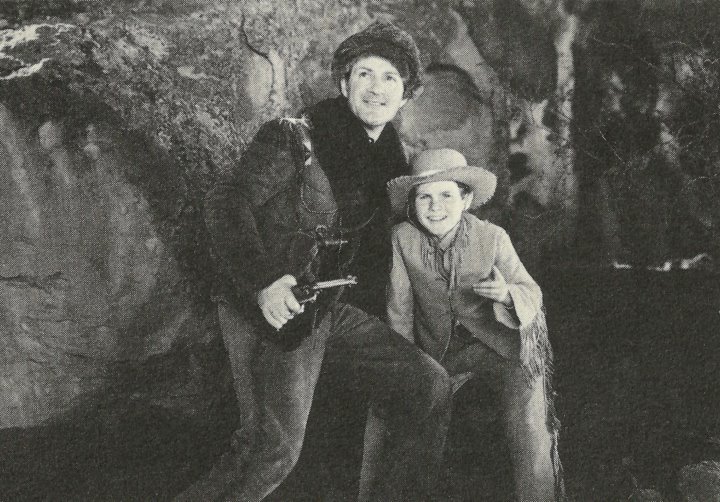

James French, later in his career. He would go on to appear in more than 240 movies between 1909 and 1945. |

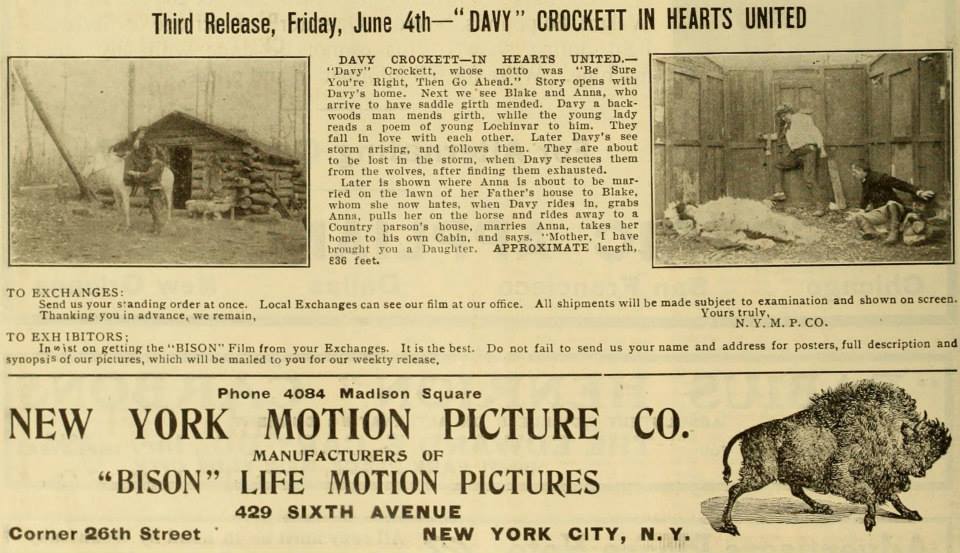

The first known film to feature Crockett, released by the New York Motion Picture Co. under the "'Bison' Life Motion Pictures" brand, was called 'Davy' Crockett—In Hearts United. There's no Alamo in this film (a good thing, as it was filmed on a small set in New Jersey). It's a reworking of the Mayo play, starring and written by Charles K. French (who was still paid ten bucks for the story). The filmmakers borrowed a wolf skin rug from a taxidermist for the scene where Davy and Eleanor are trapped in the cabin by wolves. Beyond French, it starred Evelyn Graham, Charles Bauman, Charles W. Travis and Charles Inslee. The film was directed by Fred Balshofer and was commercially released on June 4, 1909 in the United States.

Organized by Balshofer, Adam Kessel, and Charles O. Baumann, the New York Motion Picture Company had released its first film, Disinherited Son's Loyalty, just a month earlier on 21 May 1909, also under the Bison brand. Like most early film studios, NYMP filmed its western subjects in New Jersey. Balshofer, the company's official director and cameraman, became dissatisfied with the look of these films and determined that the Bison brand needed to be filmed with real western backdrops. Later in 1909, he and a troupe of actors traveled to Los Angeles and established a base of operations in Edendale.

The plot of the film, according to Moving Picture World (May 8, 1909, p. 609), opens with a young beauty named Anna and her gentrified fiancé Blake (replacing the characters of Eleanor and Neil in the play), approaching the Crockett home with a broken saddle girth, asking for help. Rough-hewn Davy mends the saddle as Anna reads him the poem of Lochnivar. They fall in love (no time for backstory or character development in a one-reeler). Then Anna and Blake leave the cabin but get lost in the stormy woods, where they are chased by wolves, but frontier-savvy Davy rescues them. Later, Anna is about to be married to Blake on her father's front lawn when Davy rides up on horseback ala Lochnivar, scoops Anna up, and whisks her away—sort of an early 20th Century, backwoods version of The Graduate. They ride to the country parson's house, marries Anna, takes her home to his own cabin, and says, "Mother, I have brought you a daughter."

The film was a box office hit, according to Terry Ramsaye's book, A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925 (New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1926, p. 491). Unfortunately the film is now lost. French was the father of B-Western regular Ted French (1899-1978) and grandfather of Little House on the Prairie star Victor French (1934-1989).

What's interesting about the Mayo play and the filmed reinterpretations is that Davy himself is not a legendary hero—he hears the story of a legendary hero and aspires to become heroic, finding the courage and self-confidence to achieve his dream at the end of the story. He has virtually nothing in common with the real man except a name and a humble background.

The real Crockett was disappearing. Like other legendary figures: Mike Fink, Robin Hood, King Arthur (and yes, Lochinvar), he was becoming myth with no relation to the actual person—at least it looked that way, until the movies rediscovered the historical figure. One man started this rediscovery. He was a great stage actor, a writer and soon to be a director. His name was Hobart Bosworth, and he starred in the next Crockett film...

"This film proves to be strongly effective in all three necessary particulars—acting, scenery and story. The plot departs from the old stage version, but it is in the direction of consistency."

—"New York Dramatic Mirror" review of Selig's "Davy Crockett" (4/30/10, p.21) |

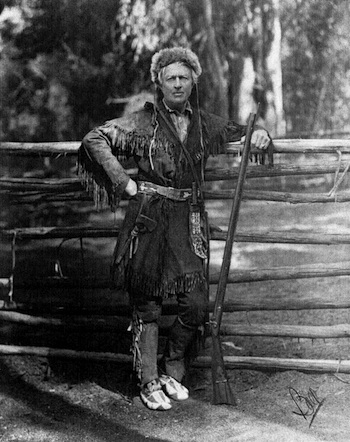

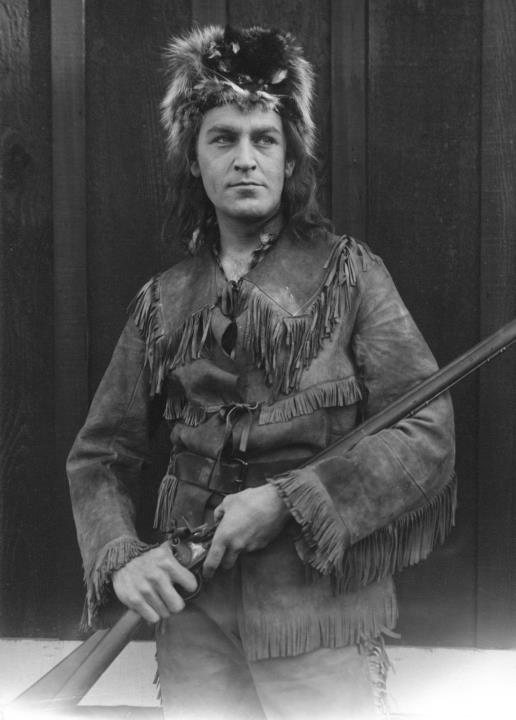

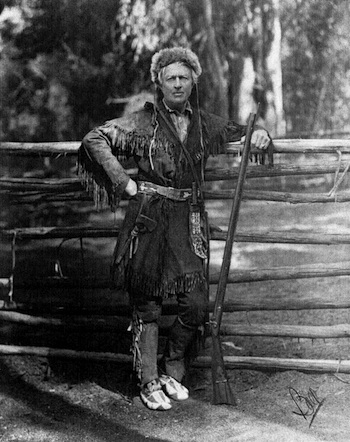

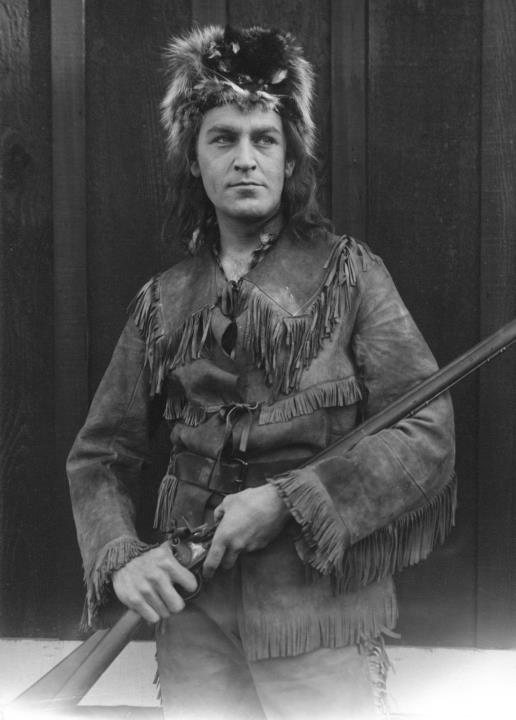

Hobart Bosworth in his Crockett garb. Bosworth is holding a gun that supposedly once belonged to the real Crockett. |

Davy Crockett in Hearts United must have been a big hit, because just a year later the Selig Polyscope Company produced a remake for their theaters, simply called Davy Crockett. Selig wanted a short (1000-foot) version of the Murdoch-Mayo play, but Hobart Bosworth, who wrote the scenario as well as starred as Davy, made some subtle but important changes.

A more perfect man could not have been chosen to fill out the story than Bosworth, because discovering the real Crockett was his life-long obsession... and it can all be traced back to the simple purchase of an antique rifle. And like Lochinvar, Hobart swooped in and saved the historical Crockett from cinematic oblivion.

Bosworth was a Broadway star who was forced to give up the stage due to respiratory illness, when he lost seventy pounds in ten weeks, as well as his voice. Bosworth moved west, and was forced to remain in the warm climate to prevent a relapse. But it was there that he found the only job an actor with a compromised voice could work in: silent films. In 1908, he was contracted to make a motion picture by the Selig Polyscope Company. Shooting was to be done in the outdoors, and he did not have to speak at all. Bosworth once said, "I believe, after all, that it is the motion pictures that have saved my life. How could I have lived on and on, without being able to carry out any of my cherished ambitions? What would my life have meant? Here, in pictures, I am realizing my biggest hopes."⁴

Although Bosworth based the story on the fictional Murdoch/Mayo play, he inserted authentic historical events and characters, using Crockett's own Narrative as the main source. The female lead in the Mayo play, "Eleanor," daughter of an aristocrat, was replaced by "Mary"—modeled after David Crockett's first wife, Mary (Polly) Finley, the daughter of a mountain trapper. In this new twist to the play, Davy courts Mary but her parents, "particularly the mother, are favorable to another suitor," mirroring Mrs. Finley favoring another suitor in the autobiography. Just like in Crockett's autobiography, Davy romances his sweetheart at a frontier frolic. He then "sees her home," but walking through the woods, they are menaced by a pack of wolves. (In the Narrative, Crockett was on a wolf hunt when he found Polly lost in the woods, and they spend the night on the porch of a cabin).

The film then reverts to the events of the fictional play: once at the deserted cabin, the wolves attack, trying to break through the door like in the play. Davy stands all night barring the door with his arm, until they are rescued that morning. David nurses his swollen arm as Mary is taken home, where she is "upbraided by her mother for her love for Davy." The film then jumps to the scene in the play where Mary is forced into marriage with her mother's choice of suitor. Davy rides up just as the nuptial services are ready, "lifts her up into his saddle and gallops away with her in true romantic fashion, emulating Lochinvar's ride." (Even though he hasn't read the poem in this version.) Mary is spirited off, "happy in her thought of wedding the man she loves." (The Moving Picture World, 4/23/1910, p. 657).

Still, the most important connection to the real Crockett was that Bosworth used a special rifle in the film: Long, sleek and beautiful, but with notches and other battle scars noticeable in the wooden stock... and, according to Bosworth, it was the actual gun that David Crockett had used at the Alamo. Bosworth's connection to the rifle began in 1903, when he was touring in a play. While shopping during his off-hours in Joplin, Missouri, he found a beautiful antique 5'-long, twenty-pound rifle in the possession of an old jeweler, who claimed it had been Crockett's rifle at the Alamo. The jeweler said he had purchased it from an old Mexican soldier who had pulled it from the dead Crockett's hands on the Alamo grounds. Was it really Crockett's? Who knows, but it certainly spurred Bosworth's interest in Crockett and infused his work on the film, which according to critics of the day was a wonderful job (it's a lost film, so that's all we have to go by).

Out of Selig Polyscope's hundreds of movies, only a few copies and scattered photographic elements of their films are known to survive. Unfortunately, Davy Crockett is not one of the surviving films. All we have today are contemporary accounts.

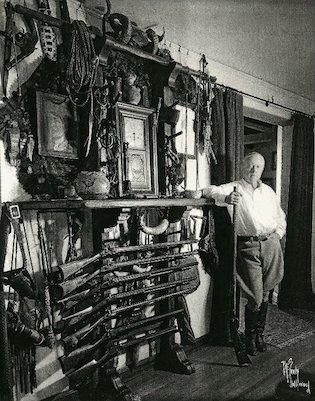

Bosworth wearing his Crockett hunting garb and rifle as "Old General Sutter" at a Rotary Club Luncheon in 1922 to promote the "Days of Gold" celebration in Sacramento. "The gun is a muzzle loading rifle that carries a 32 caliber ball and is authenticated by the U.S. Government as being the great Davy Crockett's gun, the one used in the incident that every American school boy knows when the coon in the tree said: 'Don't shoot Davy, I'll come down.'" (Published in the "San Francisco Chronicle," Tuesday evening, May 23, 1922) |

David Crockett had always stood bravely against formidable adversaries—and while Creeks, Andy Jackson, and Santa Anna were worthy foes, he now faced a brand new threat: film critics. Fortunately, they were kind to him in this film:

"In this film, a reproduction of striking scenes in the life of a historical character, the Selig players have accomplished something worth while. ... A historic character adequately presented is well worth the consideration of every serious person. Selig, in this presentation, may well claim the right to feel proud of what a motion picture can be made to say," said The Moving Picture World review (4/23/1910, p. 737).

Variety said: "Davy Crockett, according to the Selig 'story man,' falls in love with a frontier belle. The pioneer has a rival and several scenes are shown in which they display their bitterness toward each other. Both attend a corn-husking and after a tiff with Davy's rival the girl agrees to be escorted home by the pathfinder. Pretty winter scenes are shown as the couple journey to the girl's home. The scene shifts and a pack of dogs, looking wonderfully like wolves, are seen racing madly across the snow, presumably in chase of Davy and his sweetheart. Davy hears them approach and the pair make for a deserted hut, getting under its welcome shelter just in time. The "wolves" spring against the door and try to force their way in, but Davy is there with the brawny arm. He makes a bar of his arm and through the cold, long night holds the door shut against the ravenous pack. A popular picture, which was probably the base of this story, shows Davy in this pose. In the morning the girl's mother rouses the settlers with the news that daughter has not returned. Frontiersmen track the pair and finally release them. All is not yet over. The girl is forced into marriage with Davy's rival. Everything has been prepared for the ceremony. Even the minister is present. The latter personage is about to tie the knot (strangely enough in the open air during what appears to be a severe winter) when Davy gallops up on horseback and, snatching the bride-to-be carries her off while his friends keep the rest of the wedding guests from interfering. The wolf incident is admirably worked out and the reel is a capitol scenic series. RUSH.—(April 30, 1919, p. 16.)

All of this critical praise would naturally lead to a sequel, so Bosworth wrote a scenario for a sequel that stayed truer to the historical character. It begins: "Davy Crockett: Frontiersman, Patriot, Truest Type of the Men Who Made America What It Is."

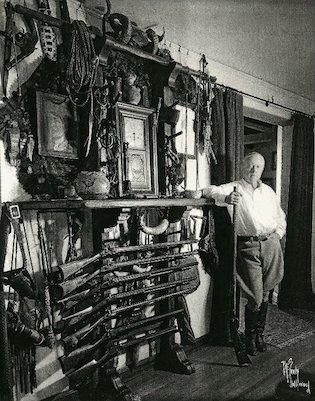

On March 4, 1928, Bosworth appeared in the 'L.A. Times' with his gun collection. He holds the Crockett rifle, and painted the portrait of Davy that hangs on the wall... Caption: "Hobart Bosworth's collection of old rifles is famous. The one in his hand belonged to Davy Crockett, and was found beside his body in the Alamo.—Photo by (Walter Fredrick) Seely." |

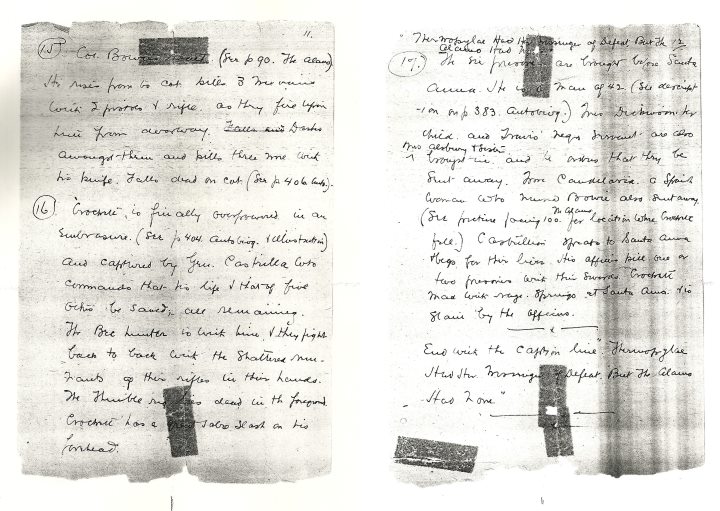

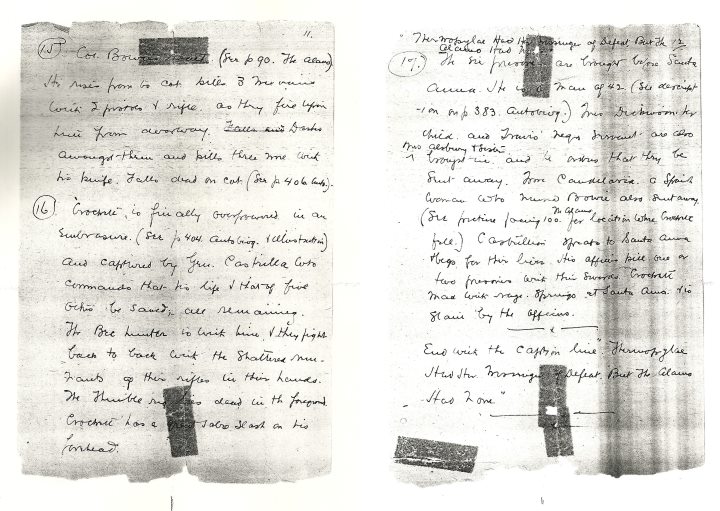

Unlike the fictional romantic melodrama that the character of Davy Crockett had been consigned to for forty years onstage and in film, this scenario, titled Davy Crockett, 2nd Series and written by Bosworth in longhand, is based on a real man and is framed by war. The story begins with, "An Incident in the Battle of Taladega, Dec. 7, 1813," and ends with the battle of the Alamo. In fact, the final scene would have been the first filmed dramatization of Crockett being captured and executed:

(Page 11) Crockett is finally overpowered in an embrasure [see p.404 Autobiography and illustration) and captured by General Castrilla (sic) who commands that his life and that of five others be saved, all remaining. The Bee hunter is with him and they fight back to back with the shattered remnants of their rifles in their hands. Then Thimblerig lies dead in the foreground. Crockett has a great saber slash on his forehead.

(Page 12) The six prisoners are brought before Santa Anna. He is a man of 42 (see description on p. 383 Autobiography) Mrs. (Dickinson) her child and Travis's Negro servant are (inserted: also Mrs. Alsbury and sister) brought in and he argues that they be sent away. Mdm. Candaleria, a Spanish woman who (nursed?) Bowie also sent away. (See ___ ___ for location where Crockett fell) Castrillon (speaks?) to Santa Anna begs for their lives. His officers kill one or two prisoners with their swords. Crockett mad with rage, springs at Santa Anna and is slain by the officers.

—————x—————

End with caption line: "Thermopylae Had Her Messenger of Defeat. But The Alamo Had None."

But plans for this sequel were interrupted on October 27, 1911, by more tragedy when studio caretaker Frank Minematsu went berserk and shot and killed Davy Crockett's director, Francis Boggs in the Selig offices. In the struggle to retrieve the gun, Selig himself was shot and wounded in the arm. Minematsu whom the Los Angeles Times dubbed "The Gentleman Janitor," claimed he shot Boggs because he was a "bad man." — it was the first celebrity murder scandal. On December 13, 1915, Bosworth reminisced about Boggs to the Woodland Daily Democrat, saying, "Francis Boggs was a great man in all ways. He had breadth, the big view, splendid initiative and great business capacity that was developing into great executive ability, and too little credit is given him as a pioneer in our new art. Time and time again I have seen credit given to this man and to that for inventions such as dissolves, close-ups, silhouettes and many other things which Mr. Boggs used before they appeared elsewhere. He had difficulty at first. The Chicago office objected to these innovations. Mr. Boggs had to make over many scenes because 'Chicago' declared they were 'too close to the camera.'" Minematsu was sentenced to life in prison and tended the gardens of San Quentin, even refusing parole back to Japan in order to care for the plants until his death. (July 28, 1937 Ukiah Repubican Press)

Bosworth would spend the rest of his life promoting and attempting to prove the legitimacy of the "Crockett rifle." He told the Bosworth Bulletin in 1932 that the rifle "has been authenticated to the satisfaction of the War Department as Davy Crockett's famous 'Betsy.' Not having been there personally at the Battle of the Alamo, I can't say definitely. But it is a splendid specimen of the drop stock, converted flintlock rifle of about 1820." Bosworth donated his incredible rifle collection to the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles in 1929... everything but the Crockett rifle, anyway. It's still in the family over a hundred years after Bosworth purchased it, and they're still trying to prove its provenance. Me? I'd just be happy to find the film!

The Immortal Alamo was the first Alamo movie, shot in San Antonio (although the actual Alamo was not used in the film), and released in 1911. It's lost now, so the only way we know Crockett was even in it is that he's mentioned in an ad for the film. At the time of this film, Mexican/American relations were foundering. With the outbreak of revolution in northern Mexico in 1910, federal authorities and officials of the state of Texas feared that the violence and disorder might spill over into the Rio Grande valley. The Mexican and Mexican-American populations residing in the Valley far outnumbered the Anglo population. Many Valley residents either had relatives living in areas of Mexico affected by revolutionary activity or aided the various revolutionary factions in Mexico. The revolution caused an influx of political refugees and illegal immigrants into the border region, politicizing the Valley population and disturbing the traditional politics of the region. Some radical elements saw the Mexican Revolution as an opportunity to bring about drastic political and economic changes in South Texas.

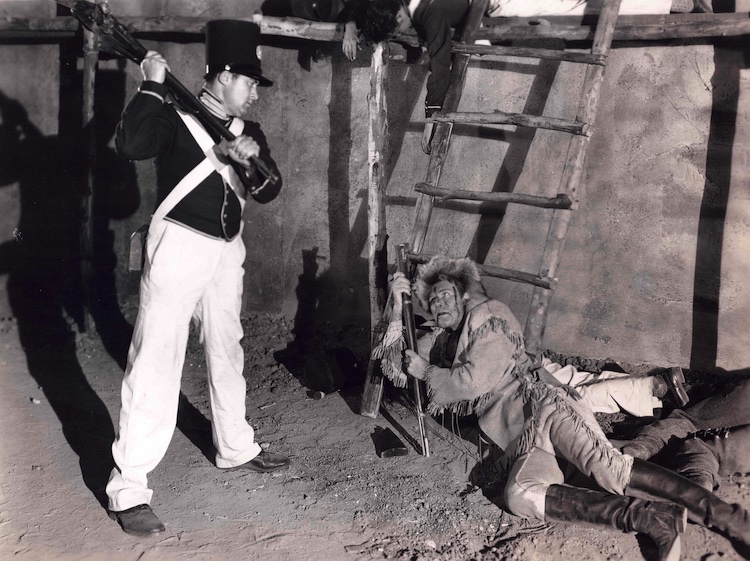

Ray Myers in "The Siege and Fall of the Alamo" from 1914. It was the only Alamo film to ever get made inside the real Alamo (but seeing as most of the Alamo fort was destroyed by then — except for the chapel — it was probably the least accurate representation of the battle ever made. |